Bat Project

Justin Boyles

Creatures of the Night

Why It Matters

Bats are often seen as spooky, or even dangerous, but they are actually one of the most beneficial mammals we have in New Jersey!

Bats are often seen as spooky, or even dangerous, but they are actually one of the most beneficial mammals we have in New Jersey.

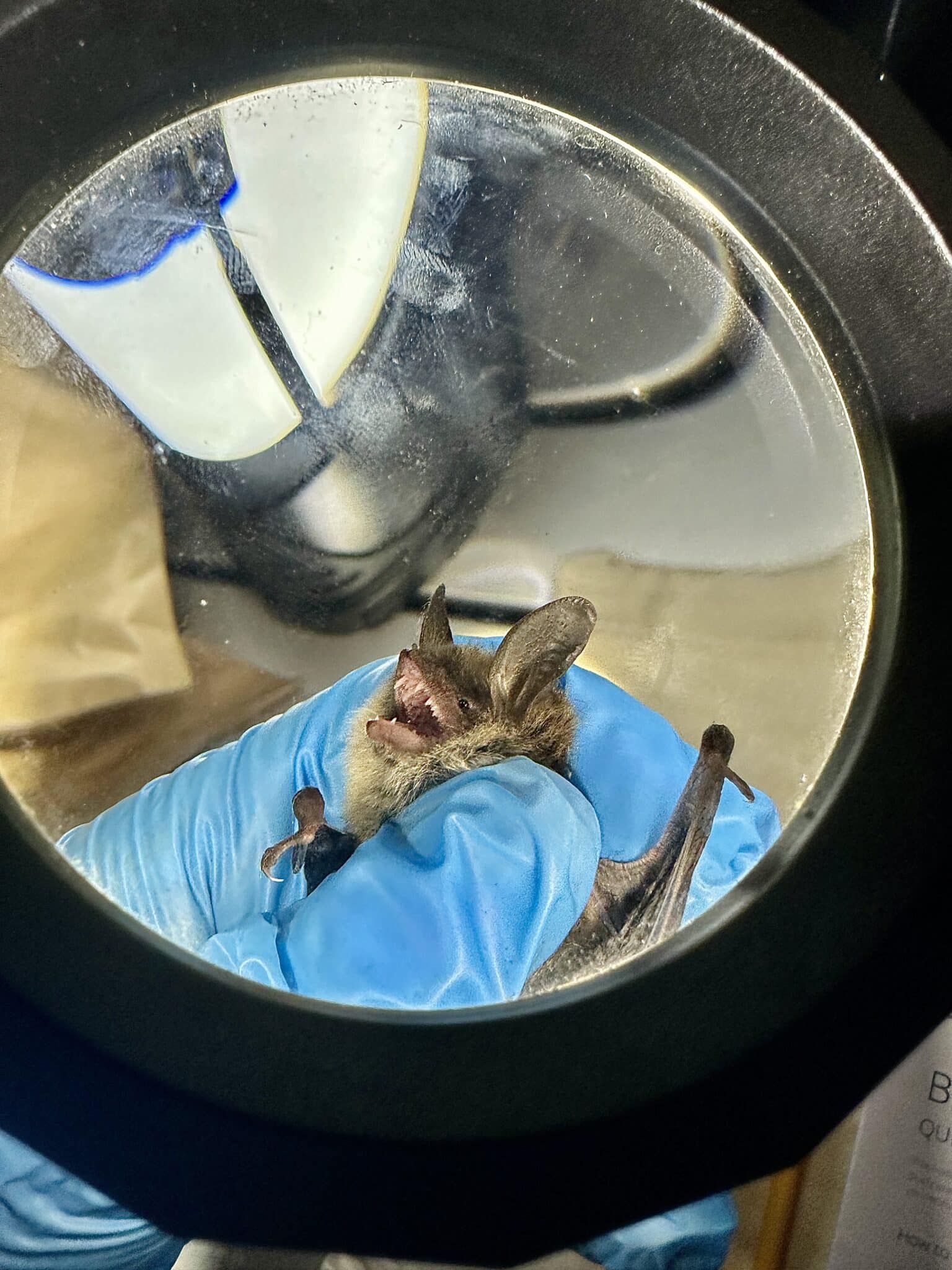

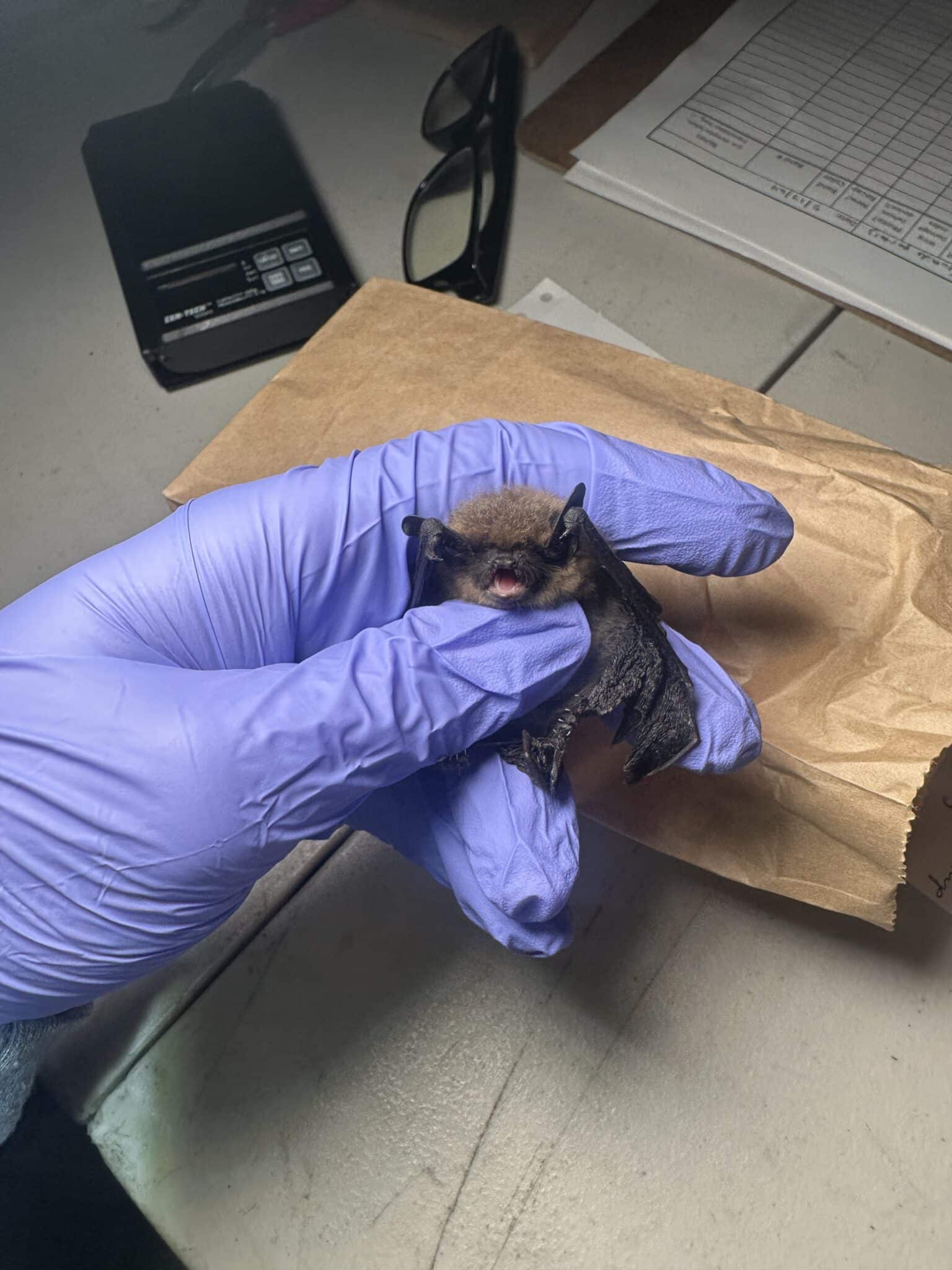

New Jersey is home to 9 species of bats. Six species are year round residents and three species are migratory.

Year round residents include the:

- Little brown bat

- Big brown bat

- Indiana bat

- Northern long-eared bat (Federally Endangered)

- Eastern small-footed bat (Federally Endangered)

- Tricolored bat

These species are active throughout the late spring, summer, and early fall but go into dormancy, hibernating in caves and abandoned mines, for the cold winter months.

Part-time residents include the:

- Hoary bat

- Silver-haired bat

- Eastern red bat

These bats migrate to southern states in the fall to over winter in milder climates.

Conservation Efforts

Conserve Wildlife Foundation is dedicated to the conservation and preservation of all rare species in the state of New Jersey, including bats. CWF takes part in a number of bat-related projects year-round that range from hands-on wildlife monitoring to working with homeowners on safe bat exclusion practices.

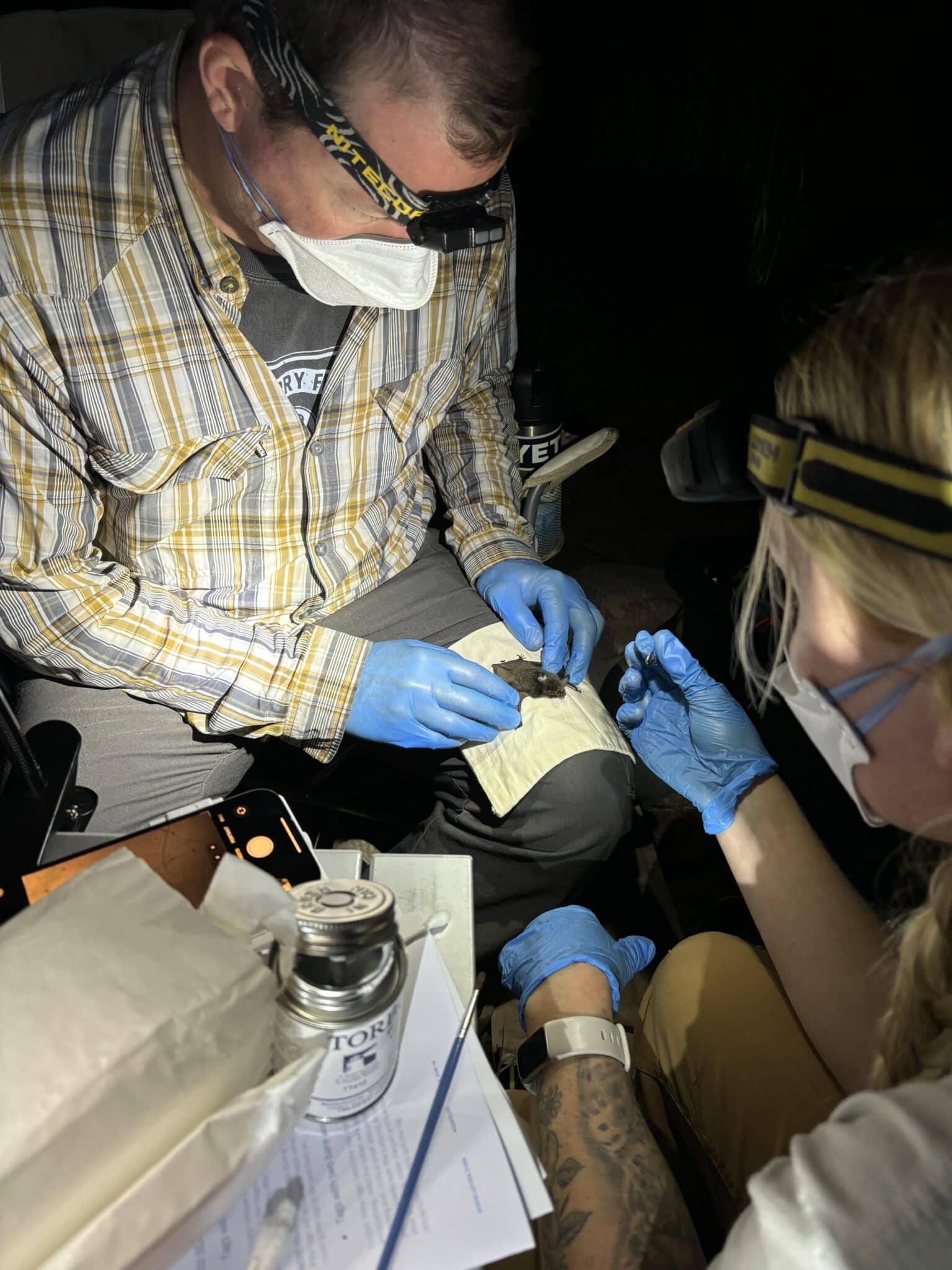

Our work in the field takes place primarily in the summer, starting with the Summer Mist Netting Project. Since the Northern long-eared bat (Myotis septentrionalis) was listed as federally Threatened in 2015, and more recently federally Endangered in 2022, we have been working to learn more about the under-surveyed species. In partnership with New Jersey Fish & Wildlife, CWF conducts mist-netting surveys through the summer in hopes of finding the now rare bat in order to track them via radio telemetry. By tracking Northern long-eared bats to their roosts and colonies, we can learn more about how they utilize their habitat and where they can be found, which enables us to better conserve the species.

Similarly, we also partner with New Jersey Fish & Wildlife on the Mobile and Stationary Acoustic Projects each summer. By using “bat detectors” to listen in to the ultrasonic echolocation calls of bats, we are able to identify which species made a given call. Stationary Acoustics involves placing these detectors at various locations spread throughout the state. Mobile Acoustics is largely volunteer-driven, with trained citizen scientists helping us in our hunt for bats by driving those same detectors around road transects. This data is submitted to the North American Bat Monitoring Program (NABat) and used to help us determine which species of bats live where in New Jersey.

The Summer Bat Count is another largely volunteer-driven program. Started by CWF and the State Endangered and Nongame Species Program (ENSP), this project relies on New Jersey residents to tell us where the bats are. If someone knows of a place where bats roost in the summertime – like an attic, barn, bat house, church, or tree – they can reach out to us and sign up to report how many bats emerge from the roost through the summer. These data give us a better understanding of how NJ’s bats are distributed, what conditions they choose for roosting, population estimates and changes over time, and reproduction success.

We also focus considerable energy on education and public outreach through Bats In Buildings and our speaker series, Creatures of the Night. Bats are a misrepresented and misunderstood group of animals and much of the fear surrounding them is due to myth and misinformation. We try to dispel this fear through education, lively presentations, and even bat walks! Our Bats In Buildings project also provides resources for homeowners with “house bats” to help them determine their best course of action, like safely excluding the bats. We provide resources on how to build and install a bat house, as well as an up-to-date list of professional bat excluders in the state equipped to safely and legally perform a bat exclusion (New Jersey’s “safe dates” for bat eviction are April 1-30 and August 1-October 15).

Threats to Bats

Bats, like many other species, have faced an unprecedented threat to their populations due to a number of causes. Some of the biggest threats bats face is the loss of forest habitats and roost trees, disturbance of wintering dens, and persecution by people. Wind energy development is also a rising concern as wind farms crop up along the ridgeline corridors used by migratory bats.

Fortunately, research is showing that bat deaths can be tremendously reduced by simply shutting the wind turbines down during seasonal low-wind periods when power generation is minimal anyway. There are also studies on another innovative solution that helps to discourage bats from entering turbine airspaces – a bat deterrent system that interferes with bats’ echolocation using ultrasound.

White Nose Syndrome

In 2006, an aggressive new threat emerged in the U.S. termed White-nose Syndrome (WNS).

Named for the white fungus first observed around the noses of affected bats. Attacking during winter hibernation when the bats’ immune response is low, the fungus led to mass bat death in affected areas. Tens of thousands of NJ bats – and over 6 million bats across North America – have died.

Since its first appearance, White-nose Syndrome has spread to at least 32 U.S. states and 5 Canadian provinces and was first confirmed in New Jersey in

January 2009. The disease has severely depleted the state’s most important hibernacula, reducing the populations of affected species by almost 98%.

Much is still unknown about WNS and its spread, much less its consequences. The federal government, states, several universities, and private organizations are working hard to track and understand WNS. Without action, their populations could continue to fall, driving some species to extinction.

Contact Us

Wildlife Biologist

Leah Wells

leah.wells@conservewildlifenj.org