Balaenoptera musculus

Type: mammal

Status: endangered

Species Guide

Blue whale

Balaenoptera musculus

Species Type: mammal

Conservation Status: endangered

Federal Status: endangered

The blue whale is a large baleen whale. The largest animal alive and probably the largest animal that has ever existed, the blue whale has reached lengths greater than 100 feet and has reached weights of about 196 tons, although it averages 70 to 90 feet and weights of 100 to 150 tons. The largest individual measured 110 feet long and nearly 200 tons. As with other baleen whales, the female is larger than the male.

The blue whale’s skin is light bluish gray and mottled with gray or grayish-white; it appears distinctly blue when seen through the water. Underneath, the belly sometimes has a yellowish tinge as a result of diatoms that have attached themselves in cold water; hence the nickname “Sulphur Bottom Whale.” The belly’s ventral grooves also extend to or just beyond the navel. Almost U-shaped, the broad, flat rostrum or snout has a single median dorsal ridge. The pectoral flippers are long and thin, while the dorsal fin is very small and far back.

Instead of teeth, it has great plates of horny baleen which extend from the upper jaw. These are used to strain food from large mouthfuls of water. It has two blowholes and the blow is high and columnar. Like the fin whale (and unlike the sei whale) the blowholes appear before (not with) the dorsal fin as the whale surfaces.

The dorsal fin is situated far back on the body and is not as tall or steeply angled as the fin or sei whale’s. The coloration and patterning of the mottled skin is individually distinctive, similar to a human’s fingerprint, and allows researchers to identify and track individual whales.

Distribution & Habitat

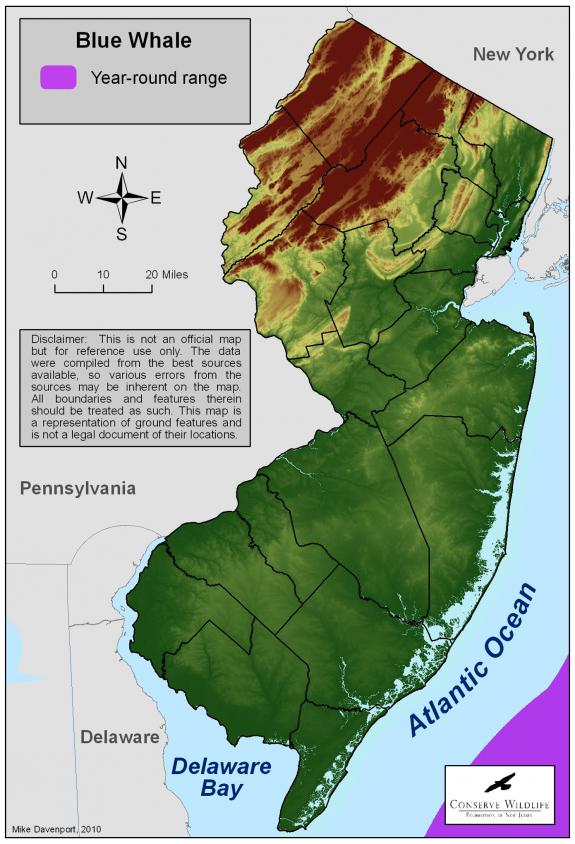

Blue whales live within all of the major oceans of the world, primarily in temperate and polar waters. They are not usually encountered within New Jersey’s coastal waters. Their migration patterns are poorly understood compared to some whale species, such as the humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae). It appears that blue whales may follow a similar migration as humpbacks within the western North Atlantic Ocean, feeding during spring, summer, and fall in northern latitudes and then spending the winter in the West Indies. Some individuals, however, may remain in their feeding grounds year-round.

Within the North Atlantic Ocean, blue whales are typically found off the coast of Greenland and eastern Canada in the summer and may be found as far south as Cape Cod. Their winter distribution is less well-known but some individuals have been observed in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean. They typically are not seen over the continental shelf, preferring deeper waters. According to the New Jersey Endangered and Nongame Species Program, there are no sightings currently documented within New Jersey waters for this species.

Diet

Blue whales primarily feed almost exclusively on tiny crustaceans known as krill. They feed by filter feeding with their mouthful of baleen. They do so by taking a large mouthful of both prey and water, closing their mouth, and then pushing the water out of their mouth using their enormous tongue. The prey items are then left within the mouth, trapped by the strips of baleen, and ready to be swallowed. Blue whales may also prey on small fish, but this is a small portion of their diet compared to krill.

Life Cycle

During the summer, blue whales will spend most of their time feeding and building-up fat in the cold waters of the North Atlantic. These fat stores will be necessary for the long migration to their winter breeding and calving grounds. The winter breeding grounds are most likely located in warmer subtropical or tropical waters. Mating, as well as the birth of calves, occurs during the winter.

Little is known about the blue whale mating. Like other baleen whales, it is likely that long-term bonds are rare. Blue whales are thought to be sexually mature at 5-15 years of age. Females will give birth once every 2-3 years. Blue whale pregnancy lasts for 10-12 months. New born calves are approximately 20-23 feet long, weigh up to 4 tons, and grow quickly feeding on the milk of their mother. They will nurse on their mother’s milk for 6-7 months. Males play no role in raising their young.

The only predator of the blue whale, aside from humans, is the killer whale (Orchinus orca). Blue whales may live to an age of 80-90 years, or even longer.

Current Threats, Status, and Conservation

All of the large whale species have been at risk of extinction due to a long history of whaling. The principal attraction of whaling was the whale's blubber, which yielded oil ideal for lamp oil and, much later, in the production of margarine. Baleen was also of value. Whalebones were also used in the manufacture of glue, gelatin and manure. Besides being eaten by humans, the meat has also been used in dog food and, when dried and crushed, cattle feed.

Commercial whaling of blue whales ended in 1966 due to the decline of the species. It was listed by the federal government as endangered in 1970 and, as a result of that federal status, was automatically added to the New Jersey endangered species list following enactment of the New Jersey Endangered and Nongame Species Conservation Act in 1973. Blue whales are provided with additional protection with the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972.

“Collisions with ships are an increasing threat to blue whales.”

Despite the ban on hunting, blue whales face a number of threats, all of which are caused by humans. These threats include entanglement in fishing gear, collisions with ships, and habitat impacts including noise pollution.

One of the threats facing blue whales is entanglement in fishing gear. Blue whales may become wrapped-up in nets and/or fishing line around their tail, mouth, or other body part. Discarded nets and lines may float at sea for decades or become snagged on rocks or debris at the ocean bottom. Once entangled in fishing gear, the whale may face an agonizing death, pulling the gear along while it swims for many days, months, or even years, as the gear slowly cuts through their body and causes swimming to become more difficult. Scars on whale bodies are often an indication of a previous entanglement from which they escaped.

Collisions with ships are an increasing threat to blue whales. The increasing number of large and fast ships results in whales and ships being in close proximity more often. Unfortunately, whales do not always know or have time to react to the approach of large ships and they get hit, usually resulting in their death.

Negative impacts to whale habitat may take the form of development, pollution, noise, overfishing, and climate change. Shipping channels, aquaculture, offshore energy development, and recreational use of marine areas may destroy whale habitat or displace whales which would normally use the area. Oil spills and other chemical pollutants are also a threat to whales and the prey which they feed on.

Another form of pollution is noise pollution. Whales’ primary means of communication, navigation, locating food, locating mates, and avoiding predators and other threats is through their sense of hearing, which is much more highly developed than that of humans. Noise pollution created by ship traffic or offshore construction may negatively impact whales by disrupting otherwise normal behaviors associated with migration, feeding, alluding predators, rest, breeding, etc. Any changes to these behaviors may decrease survival, simply by increasing efforts directed at avoidance of the noise and the perceived threat. Active sonar, such as that used by the Navy, also threatens marine mammals by disrupting navigation, foraging and communication abilities. There have been instances of whale stranding and death caused by acoustic trauma. This may be due to a fatal injury within the structure of the ear or may result from the distressed animal surfacing too rapidly and developing nitrogen bubbles within their blood (decompression sickness). In addition to the direct threat posed by active sonar, it may indirectly harm marine species by causing changes in behavior.

The potential impacts of global climate change are another potential cause for concern for blue whales. This issue may be the greatest long-term threat to the marine habitat and its species. Climate change may significantly alter the chemical balance of the seas, offshore currents, and plankton distribution and abundance, thereby affecting migration routes of marine species and impacting the entire food web.

It is unknown whether blue whales are recovering throughout much of their range. Ship strikes and entanglements may be slowing their recovery. Within the North Atlantic Ocean, the best available estimate of their population is approximately 100-555 individuals. It is estimated that, prior to commercial hunting, there was an estimated 1,100-1,500 blue whales in the North Atlantic. The global population, which may have once numbered up to 210,000 individuals, may now be as low as 4,000.

Although blue whales are large animals, we don’t currently know a great deal about their habitat use off the coast of New Jersey. It is likely, in fact, that they may not occur within New Jersey’s waters which only extend 3 nautical miles off the coastline. It is likely, however, that they do occur within the ocean waters beyond 3-nautical miles. It is unknown whether they may be using those offshore waters as a migratory pathway between their summer feeding grounds in the north and their winter breeding grounds in the south. Surveys are currently being conducted off the New Jersey coastline to determine where whales are located, how many individuals are there, and during what time of year. Based on these findings, further knowledge regarding their habitat use in New Jersey waters may be gained and attention may then focus on protecting important habitats.

References

Text derived from the book, Endangered and Threatened Wildlife of New Jersey. 2003. Originally edited by Bruce E. Beans and Larry Niles. Edited and updated Michael J. Davenport in 2010.

Scientific Classification

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Mammalia

- Order: Cetacea

- Family: Balaenopteridae

- Genus: Balaenoptera

- Species: B. musculus