Lasmigona subviridis

Type: invertebrate

Status: endangered

Species Guide

Green floater

Lasmigona subviridis

Species Type: invertebrate

Conservation Status: endangered

Identification

The green floater is a small, rare mussel with an ovate trapezoid bivalve (two shells hinged together) shell that is fragile and thin. The posterior ridge is rounded. The outer shell is light yellow or brown with many green rays, especially in juveniles. The nacre (inside of the shell) can be white to blue and is iridescent towards the posterior end.

Distribution & Habitat

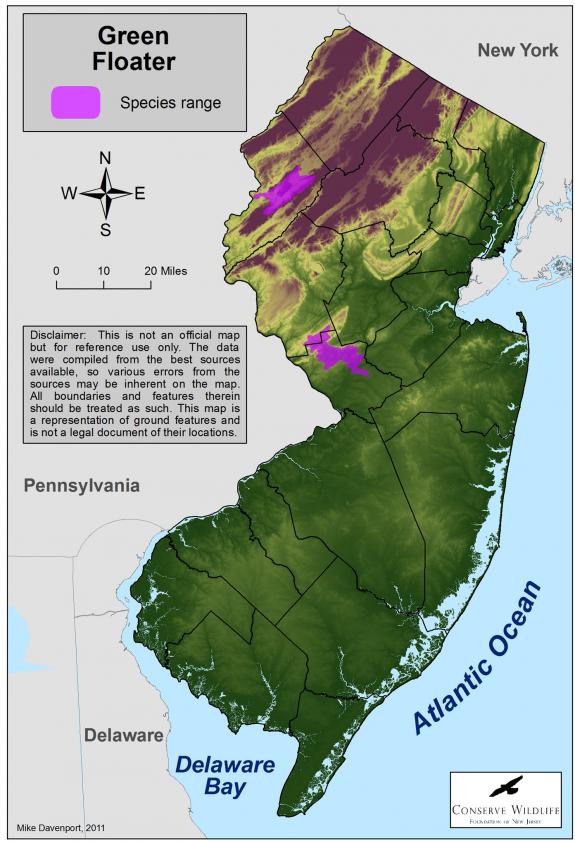

The green floater can be found from the Cape Fear River Basin in North Carolina north to the Hudson River Basin and westward to St. Lawrence River Basin in New York. In New Jersey, the species once occurred in the Passaic, Raritan, Delaware, and Pequest rivers, but is now represented by a single known individual in the Stony Brook in Mercer County. Recently, a green floater shell was discovered by state biologists in the Pequest River.

This species can be found in smaller streams, most often in pools and eddies with gravelly and sandy bottoms. It is avoids areas with strong currents. The host fish is not known. There is some evidence that the green floater may not require a host fish in order to complete its life cycle.

Diet

Adult freshwater mussels are filter-feeders. They strain plankton (microscopic plants and animals), bacteria and other particles from the water column. The larval stage of the freshwater mussel, known as glochidia, are external parasites and feed on a host (usually a fish).

Life Cycle

Although many species of mollusks are hermaphrodites (one individual has both male and female reproductive organs), freshwater mussel sexes are generally separate. During spawning, males release sperm directly into the water. If a mature female happens to draw-in the sperm through its siphon, the eggs which are contained within her body will be fertilized. The eggs then develop within the female’s gills into the larval stage of the mussel known as “glochidia”. This period of larval development within the female’s body may last a few days to several months. At the end of this stage, up to several million glochidia will be expelled into the water through the female’s exhalent siphon.

Glochidia are microscopic and have a thin shell with two valves. Once released from the female, glochidia must find a host (usually a specific species of fish) on which to attach. Each species of freshwater mussel has its own specific species of fish that can serve as a host for the glochidia. The glochida effectively become a parasite on the fish, attaching to the gills, scales, fins or even eyes of the host fish. While attached to the fish, the glochidia feed on them, much like a flea or tick feeds on terrestrial mammals. If the glochidia do not attach themselves to a host fish, they will die.

While attached to the host fish, the glochidia go through a metamorphosis, transforming into a juvenile mussel which looks like a much smaller version of the adult. After anywhere from 6 to 160 days, the juvenile mussel will fall off of the host fish and begin its life in the bottom of the water body. If the appropriate substrate is available, it will burrow into the bottom sediment. Juvenile mussels spend their first year of life beneath the substrate.

Growth of the mussel is most rapid while it is young. The average age at which freshwater mussels become sexually mature is six years. Once a freshwater mussel reaches maturity, its chances for survival increase dramatically. Some species may live as long as 100 years or more.

Although very slow-moving, freshwater mussels are capable of moving along the substrate using their powerful foot. A mussel “track” can sometimes be seen in the mud or sand next to a mussel which has recently moved. During the winter in New Jersey, freshwater mussels will burrow into the sediment and enter a period of dormancy.

Many small aquatic animals will feed on the mussel glochidia. Adults may be eaten by raccoons, muskrats, otters, bears, herons, some waterfowl, some turtles, and large fish such as sturgeon.

Current Threats, Status, and Conservation

One in ten of North America’s freshwater mussel species has gone extinct in this century. Meanwhile, 75% of the remaining species are either rare or imperiled. This alarming decline is directly tied to the degradation and loss of essential habitat, and the invasion of exotic species such as the Asian clam. Exotic species compete for space and food with native mussels.

Destruction of freshwater mussel habitat has ranged from dam construction, channelization, and dredging to siltation and contaminants. Dams alter the physical, chemical, and biological stream environment, sometimes destroying 30% to 60% of the mussel fauna upstream and downstream of the construction. The most harmful effect of dams, however, is the elimination of host species and resulting disruption in the reproductive cycle. Increased silt loads and shifting stream bottoms caused by erosion also threaten mussel habitats, as do contaminants such as heavy metals and pesticides, and discharge from sewage treatment plants.

Green floaters were listed as state endangered in late 2002. With only one live individual found within the state in recent years, it is possible that the species is no longer present. More surveys are needed in areas of the Stony Brook and Pequest River before determining if the species can be considered state extirpated. Federal and state Clean Water acts, stream encroachment rules, environmental reviews of proposed development projects and the state Endangered Species Act serve to help protect existing populations.

Surveys for endangered and threatened freshwater mussel species are currently being conducted each spring, summer, and fall. It is recommended that such surveys continue in order to determine special distributions, population sizes, and age distributions. Threats to populations, such as barriers to host fish and glochidia movement, must also be further explored. Sufficient buffer areas along streams should also be created and stream bank restoration efforts encouraged. Lastly, protection classifications of streams with endangered and threatened freshwater mussel species should be upgraded in order to protect water quality.

References

Text derived from the book, Endangered and Threatened Wildlife of New Jersey. 2003. Originally edited by Bruce E. Beans and Larry Niles. Edited and updated Jeanette Bowers-Altman and Michael J. Davenport in 2010.

Scientific Classification

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Mollusca

- Class: Bivalvia

- Order: Unionoida

- Family: Unionidae

- Genus: Lasmigona

- Species: L. subviridis