Limulus polyphemus

Type: invertebrate

Status: not ranked

Species Guide

Horseshoe crab

Limulus polyphemus

Species Type: invertebrate

Conservation Status: not ranked

IDENTIFICATION

Horseshoe crabs are unmistakable: they look almost like dark brown hubcaps and move like army tanks. Their name comes from their shape, which is similar to a horse’s hoof. Females are, in general, about 20% larger than males. Although they are called crabs, they are actually more closely related to arachnids like spiders and scorpions, than to true crabs. Horseshoe crabs are prehistoric: they have not undergone significant evolutionary change in over 400 million years, almost 200 million years before the first dinosaurs.

There are three divisions to the body. The prosoma is found at the front of the body and contains the heart, brain, and digestive system. The opisthosoma is found in the middle of the body and consists mostly of the muscles that control the animal’s gills and tail. Last is the tail (known as the telson), which horseshoe crabs use to right themselves if they are upturned by waves during spawning.

Horseshoe crabs have six pairs of legs. The first is known as the chelicerae and is used for placing food in its mouth. The next pair is known as the pedipalps; they are used for walking, but in males they are modified into boxing-glove-like claspers and additionally used for grasping the female during spawning. The remaining four pairs of legs are the pushers and are used for moving. Further towards its tail are the gills, which are used for both breathing and for assisting to push itself through the water.

Though possessing a somewhat fierce appearance due to their sharp-looking tails, angular exoskeletons, and many claws, horseshoe crabs are completely harmless to humans. Their claws have a weak grip, and they do not bite or use their tails as a weapon.

Distribution & Habitat

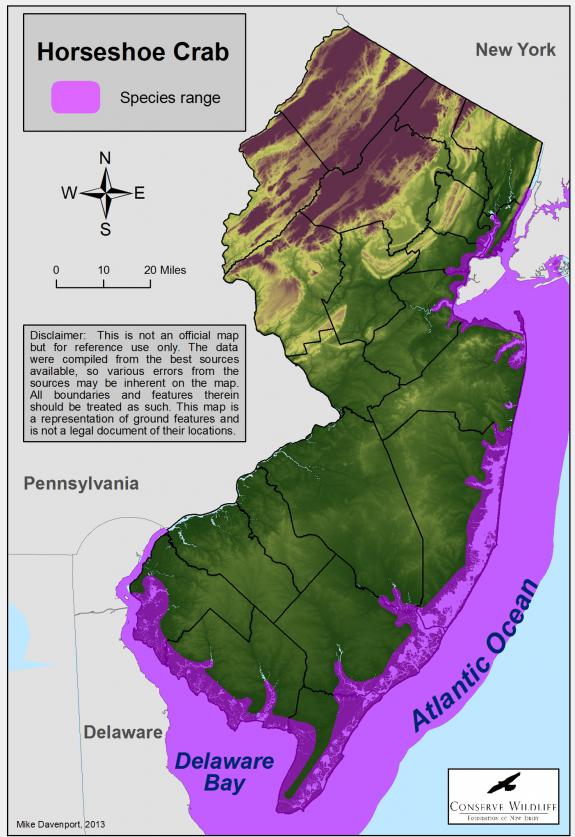

There are four species of horseshoe crab still alive, but only one (the Atlantic horseshoe crab) lives in the Western Hemisphere. They can be found all along the Atlantic Coast from Nova Scotia, Canada down to the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico, but the majority live in Delaware Bay. The largest concentration of breeding horseshoe crabs anywhere in the world can be found around the Bay each spring. The Bay is particularly ideal because of its relatively shallow depth, allowing the water to warm quickly after winter and stimulate horseshoe crab spawning. When not onshore for spawning season, horseshoe crabs live offshore in deeper waters. Some have been found at depths of over 600 feet, but studies indicate they prefer depths of less than 100 ft.

Diet

Horseshoe crabs feed on marine worms, small clams, mussels, crustaceans, snails, and slugs, but they are largely scavengers.

Life Cycle

During the full moon of late May or early June each year, horseshoe crabs undergo a “local migration.” They travel from deeper waters off the coast to the shores of sandy beaches in order to reproduce. Each female digs a hole at the water’s edge and lays between 3,000 and 10,000 eggs. While she does this, several males hold on to her while releasing sperm. The female then buries the cluster of eggs under a few inches of sand. By the end of the spawning season, each female will have laid about 80,000 eggs.

These eggs take about two weeks to hatch, and the newly-hatched horseshoe crabs immediately return to the water. They will swim for about six days before settling on the bottom in the shallow water near the beach. About 20 days after hatching, the young will molt their hard outer shell, or exoskeleton, for the first time. They will molt several times by the end of their first year, but will still be only about half an inch wide. By age three or four, however, the now larger horseshoe crab will only molt about once a year, usually during the summer. In all, horseshoe crabs will molt at least 15 times before reaching sexual maturity at age 9 or 10, at which point they will begin the annual migration to the shore to spawn.

Horseshoe crabs are believed to live about 20 years in the wild.

Current Threats, Status, and Conservation

Horseshoe crabs are highly valued by conch and eel fisherman, who use them as bait. Additionally, horseshoe crab blood contains a substance called Limulus amebocyte lysate (also known as LAL), which clots in the presence of bacteria. For this reason, it is valuable in the pharmaceutical industry, which uses it to test for contamination of drugs and medical equipment. Though crabs used for this purpose are returned to the ocean, it is estimated that between 10% and 30% die as a result of the process.

Because of this high demand for horseshoe crabs, populations along the East Coast, and particularly in Delaware Bay, are in serious decline. The Atlantic horseshoe crab is currently considered “Near Threatened” by the IUCN.

While not currently listed as a threatened species by the State of New Jersey, there is currently a moratorium on the harvest of horseshoe crabs within the state. With this law, it is illegal to remove a horseshoe crab, dead or alive, from its habitat in the wild.

Complicating the issue is the fact that at least 11 different species of shorebird rely on horseshoe crab eggs as their primary food source for about 2-3 weeks during their migration. These birds are migrating to their breeding grounds in the Arctic, some from as far away as the southern tip of South America, and the availability of nutrient-rich crab eggs during this time is critical. Recent declines in the horseshoe crab population have triggered similar and more drastic declines in shorebird populations. Even though immediate action may not be needed to save the Atlantic horseshoe crab from extinction, immediate protection of horseshoe crabs is necessary to protect the species that rely on them.

References

- Manion, M. M., R. A. West, and R. E. Unsworth. Economic Assessment of the Atlantic Coast Horseshoe Crab Fishery Report to the Us Fish and Wildlife Service. Cambridge, MA: Industrial Economics, Inc., 2000.

- Niles, Lawrence J., Joanna Burger, and Amanda Dey.Life Along the Delaware Bay: Cape May, Gateway to a Million Shorebirds. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2012.

- “The Amazing Horseshoe”. 2009. The Horseshoe Crab: Natural History. Ecological Research & Development Group (ERDG). Accessed: August 2, 2013. Available at: http://www.horseshoecrab.org/nh/hist.html.

- World Conservation Monitoring Centre.”Limulus polyphemus“.1996. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2013.1. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Accessed: August 2, 2013. Available at: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/11987/0.

Text written by Taran Catania and Matt Danihel in 2013.

Scientific Classification

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chelicerata

- Class: Merostomata

- Order: Xiphosura

- Family: Limulidae

- Genus: Limulus

- Species: L. polyphemus