Myotis lucifugus

Type: mammal

Status: endangered

Species Guide

Little brown myotis

Myotis lucifugus

Species Type: mammal

Conservation Status: endangered

IDENTIFICATION

As its common name suggests, the little brown myotis is relatively small, averaging 10 grams in weight and measuring between 2 and 4 inches in length. The wing span of this bat ranges from roughly 8 ½ to 10 ½ inches. Its fur color varies among different shades of brown, including olive, gold, and reddish, and often has luster. Its wings are mostly hairless and dark brown or black in color.

Compared to its closest NJ relatives, the little brown bat has larger hind feet than the Eastern small-footed bat (M. leibii), longer and thicker toe hairs than the Indiana bat (M. sodalis), and smaller ears than the Northern long-eared bat (M. septentrionalis). Female little browns are slightly larger than males, and will weigh more than males in the winter. The average flight speed of this bat is around 12.4 miles per hour, and it is capable of speeds up to 21.7 mph.

Distribution & Habitat

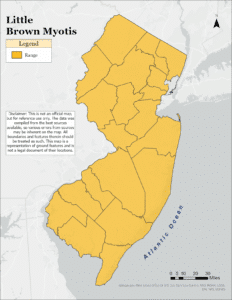

The little brown myotis is commonly found throughout much of North America, from the forested areas of southern Alaska, across southern Canada, and all the way down through the northern regions of Mexico. Individuals have been found in Kamchatka (Russia) and Iceland, but these occurrences are thought to result from accidental human transport. While its range is vast, the little brown bat is absent from certain areas of the United States including most of Florida, southern California, the southern Great Plains, and coastal areas of Virginia and the Carolinas.

Its habitat preference varies regionally, but this bat mainly resides in forested lands along riverbanks or near other water sources. The little brown bat is also able to thrive in dry areas, relying on moisture that collects on rocks or condensation that forms on its own fur. Further showing its adaptability, the little brown bat is one of the few northeastern species to regularly roost in man-made structures like barns, attics, eaves, and steeples. This common “house bat” is indeed among the most familiar to people.

The little brown bat utilizes three different types of roosts during day, night, and hibernation. The most important factors for each are suitable temperature and moisture levels, protection from predators, and darkness (its Latin species name, lucifugus, means “avoiding the light of day”). Day roosts are typically in tree crevices, beneath loose bark, or in buildings, but may be found in rock and woodpiles as well. Female little brown bats form large maternity colonies from spring through summer – numbering sometimes in the hundreds or even the thousands if space allows. Maternity roosts are chosen specifically for their warmth and safety, since this is where the mothers give birth and raise their young. Male bats are mainly solitary and are far more flexible about where they roost. Night roosts are often a distance away from the day roost, closer to preferred foraging areas and in larger confined spaces where bats can congregate for warmth while they rest and digest between periods of feeding. The separation between day and night roosts is also likely a predator deterrent.

Hibernacula are generally established in caves or abandoned mines where temperatures remain steadily above freezing and humidity is high. Little brown bats may hibernate in dense clusters, sometimes among bats of other species. They are true hibernators, dropping their heart rate, respiratory rate, and body temperature to conserve stored energy during the long months underground.

Diet

Myotis lucifugus forages over water bodies and open spaces like meadows and cliff faces, primarily for insects including mosquitoes, midges, moths, and beetles. These bats, like others, are incredibly valuable to their ecosystems and to the human economy. A single little brown bat consumes more than half its own body weight in insects each night from spring through fall; it may catch 1,000 or more mosquito-sized insects an hour during peak foraging. Nursing females are even more voracious, consuming up to 110% of their own body weight in insects each night.

Like other insect-eating bats, little browns use echolocation to navigate and find their prey. These bats emit high-frequency calls (around 20 pulses per second) while searching.

The echoes reveal the size, shape, distance, and trajectory of insects, enabling bats to follow their movements and ultimately snatch their prey from the air. As they hone in, bats increase their calls to up to 200 pulses per second in what is referred to as the “feeding buzz.”

Life Cycle

The little brown myotis begins its breeding season in August and continues into the fall, just prior to hibernation, when bats engage in ritualistic mating swarms at their hibernacula. Females store sperm over the winter and ovulate in the spring, delaying pregnancy until food resources are available again. They arrive at their maternity colonies around mid-May, and pups are born in late May or June following a 50-60 day gestation period. Females give birth to just one pup per year. Males live separately from females and are not involved in pup rearing. Within hours after birth, a pup’s eyes and ears are open and it gains full hearing sensitivity by day 13.

Little brown myotis pups nurse for approximately four weeks until they are nearly full-grown and strong enough to begin flying and foraging on their own. Sexual maturity is reached at approximately one year. The little brown bat is among the longest-lived mammals for its size, living up to 30 years or more.

Current Threats, Status, and Conservation

Currently, the little brown myotis is classified as a “least concern” species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. The species is abundant throughout the United States but has been severely impacted by the fungal disease known as White-nose Syndrome.

The White-nose fungus (Pseudogymnoascus destructans) grows incredibly well in the cold, moist environments of caves and mines, where it invades the tissues of hibernating bats during winter. The infection causes wing deterioration, water loss, and arousals that cost bats their critical energy reserves. Mortality rates exceeding 95% have been documented at winter dens across 25 U.S. states and 5 Canadian provinces (as of October 2014).

Conservation efforts include tracking the effects of White-nose Syndrome, restricting recreational cave access to slow the Syndrome’s spread, educating homeowners and wildlife control companies about the proper handling of bat problems in the home, and improving the public’s awareness and sympathy toward bats.

In 2013, the New Jersey Endangered and Nongame Advisory Committee recommended an Endangered status for this species. In January 2025, the rule proposal for upgrading the species status was finally adopted.

- Learn about the work being done to research and protect NJ’s bats at our Bat Project webpage.

References

- University of Michigan Museum of Zoology

- Bat Conservation International

- Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History

Text written by Heather Kopsco and MacKenzie Hall in 2014.

Scientific Classification

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Craniata

- Class: Mammalia

- Order: Chiroptera

- Family: Vespertilionidae

- Genus: Myotis

- Species: M. lucifugus