Perimyotis subflavus

Type: mammal

Status: endangered

Species Guide

Tricolored bat

Perimyotis subflavus

Species Type: mammal

Conservation Status: endangered

IDENTIFICATION

This bat, formerly called the eastern pipistrelle, is the only member of its genus. It is a small bat, measuring about 2 inches in body length (up to 3.4 inches including the tail) and weighing up to 8 grams. Its fur is yellowish brown, with a namesake tri-coloration that comes from the individual hairs on the bat’s back, which are dark at the base and tip and yellowish brown in the middle. This trait distinguishes the species from other small bats of eastern North America, whose back hairs are generally light-colored with dark only at the base. The tricolored bat’s belly fur is a uniform yellow-brown. Its black wing membranes contrast with orange-red forearms. Its wingspan is 8-10 inches. In flight, tricolored bats are slow and fluttery, almost moth-like. Females are slightly larger than males.

Distribution & Habitat

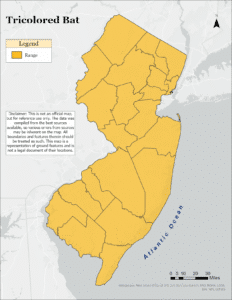

The tricolored bat is found throughout most of the forested regions of the eastern United States, plus southernmost Ontario and Nova Scotia and even along the Gulf coast of Mexico. It is one of the most common bat species in these areas.

Tricolored bats are often the first to appear along the forest edge at dusk. They can be seen foraging for food over or near water. Day roosts in summer are typically found in tree crevices and beneath loose bark. Less frequently, tricolored bats have been discovered in a variety of other accommodations, including rock crevices, caves, and even buildings. In winter, they hibernate underground in caves and abandoned mines, where temperatures and humidity levels are stable. Suitable hibernacula are rare, so the bats very often return to the same site year after year – even to the same favorable microhabitat within it. Tricolored bats are one of the first species to enter hibernation in the fall, and the last to emerge in the spring.

Diet

Tricolored bats consume a wide variety of insect prey. These include moths emerging from corn crops, other flying insects, and beetles. Thus tricolored bats are valued for their pest control services benefitting both the natural ecosystem and the human economy. Like other insect-eating bats, tricoloreds use echolocation to navigate and find their prey. They emit rapid high-frequency calls – around 20 pulses per second – while searching. The echoes reveal the size, shape, distance, and trajectory of insects, enabling bats to track their movements and ultimately snatch their prey from the air. As they hone in, bats increase their calls to up to 200 pulses per second in what is referred to as the “feeding buzz.”

Life Cycle

Tricolored bats, like many other bats, mate in large swarms just prior to hibernation, from late August to October, but will also mate again in the spring after emerging from hibernation. These bats are promiscuous and will copulate with many partners before entering a cave or other hibernacula for the winter. Females store sperm over the winter and ovulate in the spring, thereby delaying pregnancy until food resources are available again. Gestation averages around 44 days, and pups are born between May and June.

Tricolored bats typically give birth to twin offspring, while most other bats have just one. Pups are completely dependent on their mothers for sustenance (milk) and protection for about a month and will make a clicking sound to signal care. Maternity colonies average around 15 mother bats plus their pups. Males do not partake in care of the young and are not found in maternity roosts. Females will often carry their young to different roosts, switching many times throughout the summer in response to temperature changes and predator risks. Pups are capable of flight within about three weeks are completely weaned at four weeks. They reach sexual maturity anywhere between 3 and 11 months.

These bats have a typical lifespan of four to eight years in the wild, but can live up to 14 years of age.

Current Threats, Status, and Conservation

Tricolored bats are most vulnerable to predation by animals like raccoons, opossums, and snakes while roosting and may be taken by hawks and owls while in flight. General habitat loss and disturbance to hibernation sites are challenges to tricolored bats as well as other northeast species.

Like other temperate cave-hibernating bats, tricoloreds are vulnerable to the fungal disease known as White-nose Syndrome. White-nose Syndome is caused by a fungus (Pseudogymnoascus destructans) which grows incredibly well in the cold, moist environments of caves and mines, where it invades the tissues of hibernating bats during winter. The infection causes wing deterioration, water loss, and arousals that cost bats their critical energy reserves. The mortality rate for tricolored bats appears to exceed 90% in infected caves and mines. As of spring 2014, White-nose Syndrome has spread to 25 U.S. states and 5 Canadian provinces.

In 2013, the New Jersey Endangered and Nongame Advisory Committee recommended an Endangered status for this species. In January 2025, the rule proposal for upgrading the species status was finally adopted.

Learn about the work being done to research and protect NJ’s bats at our Bat Project webpage.

References

- Bat Conservation International

- University of Michigan Museum of Zoology

- Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife

Text written by Heather Kopsco and MacKenzie Hall in 2014

Scientific Classification

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Mammalia

- Order: Chiroptera

- Family: Vespertilionidae

- Genus: Perimyotis

- Species: P. subflavus