It’s a Wrap! First Season of Delaware Bay American Oystercatcher Monitoring is a Success

by Emmy Casper, Wildlife Biologist

This past winter, CWF announced a new project designed to study and monitor the population of American oystercatchers breeding along the New Jersey side of the Delaware Bay. In addition to locating nesting pairs and tracking their success, our goal is to better understand how oystercatchers utilize the bayshore habitats and what factors threaten their productivity. The data we gather with our partners at The Wetlands Institute and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service will be used to inform future management decisions. We spent the past few months working hard to conduct the project’s first season of monitoring, and we are happy to say that we have made significant progress in beginning to unravel the mysteries surrounding this understudied population.

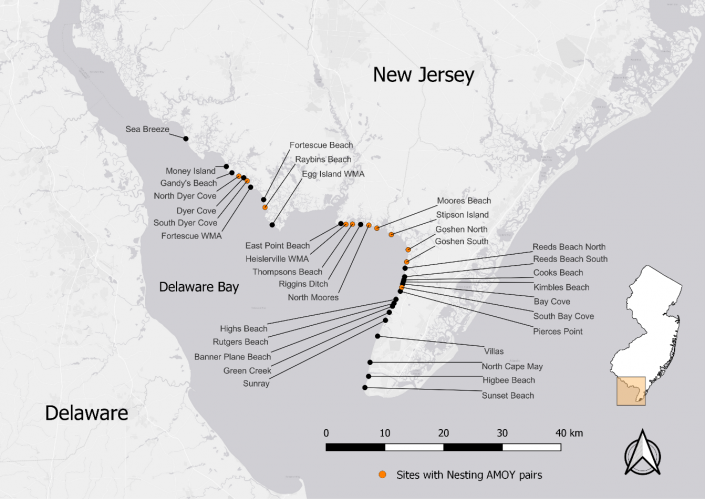

Since so little is known about this subpopulation of oystercatchers, we had a lot of ground to cover in our first season of fieldwork. First, we had to locate any breeding oystercatcher pairs across 35 sites spanning approximately 45 miles of bayshore from Cape May Point to Sea Breeze. Luckily, we had a head-start based on a preliminary census survey from 2021 that documented some already existing pairs as well as some sites with potentially suitable nesting habitat. We were also fortunate to have a dedicated seasonal technician assisting with the heavy workload. That said, figuring out how to access many of these sites was definitely a learning curve. We quickly discovered that many beaches were only reachable by boat or kayak and only during a narrow window of tide and wind conditions. Other sites were walkable, but only at peak low tides, which meant our surveys couldn’t take too long without risking becoming stranded by the rising tide.

We originally thought we would have some time in the beginning of the season to get accustomed to our new sites, but the oystercatchers had other plans. They hit the ground running and laid the first nest as early as April 7, which meant we had to learn quickly in order to keep up. By season’s end, we successfully identified 20 pairs of breeding oystercatchers along the bayshore, 19 of which had confirmed nesting attempts. This is more than we expected based on the 13 pairs recorded during the 2021 census survey. Interestingly, most of the nesting pairs (11, or 58%) were concentrated in a specific region of the bayshore spanning Stipson Island to Heislerville Wildlife Management Area. This “hotspot” of nesting pairs may indicate the existence of higher quality habitat compared to other locations, which is something we plan to examine in the future.

Once we located the nesting pairs, we had to figure out how to best monitor their productivity. Coming from beach-nesting bird work on the ocean side, I was accustomed to checking oystercatcher nests at least every other day, if not daily. However, we quickly learned that such frequent monitoring is simply not feasible on the Delaware Bay due to the remote nature of the sites and the narrow range of conditions in which they can be accessed. As a result, we relied on game cameras to enhance our on-the-ground monitoring efforts. We deployed cameras at almost every nest location and used them to document predators, verify nest fate (whether a nest hatched or failed), and pinpoint accurate causes of nest loss. In the end, the cameras proved to be crucial assets in our first season, as they helped collect valuable data about the threats impacting oystercatcher nest success.

Camera footage, combined with our on-the-ground assessments, determined that 36% of Delaware Bay oystercatcher nests hatched this season while 64% failed. Predation and flooding appear to be the leading factors, causing ~38% and 25% of nest loss, respectively. We identified a variety of mammalian species present at our sites, but fox was the only confirmed mammalian predator. Racoons and minks were observed close to nests (at times even handling eggs), but they were never caught predating a nest. It remains to be seen whether this pattern will continue next season. Other than predation, Delaware Bay beaches seem to be particularly vulnerable to flooding, in part because they are narrower than ocean beaches and they are exposed to both the bay and any neighboring marshes. Elevation measurements taken at each nest site will hopefully shed some light on what habitat conditions are most desirable for oystercatchers to mitigate the impacts of flooding.

Compared to other shorebirds like piping plovers, American oystercatchers tend to suffer from low hatch rates, but higher chick survival once eggs hatch. Surprisingly, oystercatchers along the Delaware Bay this year appeared to exhibit the opposite pattern. Our oystercatchers avoided predation in the early parts of the season, and almost half (47%) of the nesting pairs managed to hatch at least one chick. However, only four chicks survived to adulthood (0.21 fledglings per pair), indicating a much lower chick survival rate than we would expect. It is difficult to pinpoint the exact causes of chick losses, but we suspect flooding and predators played significant roles.

Perhaps the most surprising “plot-twist” of the season was the discovery of bald eagles as a source of major nest disturbance. Bald eagles were documented at almost every oystercatcher nesting location this season. Their behavior ranged from mildly disturbing (i.e., lingering around nests) to downright destructive. Camera footage even revealed bald eagles as the “predators” of two oystercatcher nests. In one scenario, a juvenile eagle appeared to accidentally crack oystercatcher eggs while carrying a large piece of wood. Just a couple weeks later another juvenile eagle stomped (intentionally!) on the nest of a different oystercatcher pair. As far as we know, eagle disturbance and “predation” are unique to our Delaware Bay birds, at least compared to their counterparts on the Atlantic Coast.

Overall, we learned a lot in this first season of comprehensive monitoring on the Delaware Bay. Oystercatcher productivity may not have been as high as we hoped it would be, but the season still had its fair share of successes. For example, thanks to assistance from our partners at The Wetlands Institute, we were able to equip seven adults and four chicks with field-readable bands. We are excited to start using re-sight data to track where our Delaware Bay oystercatchers winter and determine whether they come back to the same nesting locations/mates next year. Getting this new project up and running was also a success in itself, and we look forward to building on our progress. As the oystercatchers get ready to leave the bayshore behind for the winter, we are excited to put this first season in the books and focus on making the next season even better.

Leave a Comment

Hello! I photographed a banded American Oystercatcher on Poverty Beach in Cape May in 2015. I submitted my sighting to the oystercatcher database and this bird was banded as #38. (1106-12219). I recently became curious as to whether or not he might still be alive. I know that he was banded at Cape May Point State Park on June 27, 2011.

I would be happy to share the photo I took of him in 2015 but I am really interested in finding out if he is still alive and anything else about him. Thank you

Interesting story! Good job with all the labor-intensive research leading to your interesting observations and conclusions….”to be continued” next season. At least the remote nature of the nesting sites will protect them from human interference!

Comments are closed.