Seeing Bats In A Different Light

By Margaret O’Gorman, Executive Director

Sundays in my house usually involve the New York Times and some hard-core housework. But on a recent sunny Sunday, I found myself inMorris County, testing the limits of my flexibility as I maneuvered myself through a small opening that is the entrance to Hibernia Mine, the most important bat hibernation area inNew Jersey.

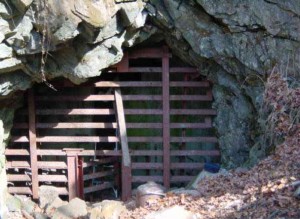

Guided, with much patience and humor, by partner-in-bat-protection John Gumbs of the Bat Research Center and Mackenzie Hall, CWF’s resident bat biologist, I climbed up into a small space atop a steel door and, displaying little grace or athleticism, managed to wedge myself in the wrong direction, then the right direction, and finally to descend into the main mine shaft of Hibernia.

Once inside, aided by a headlamp, my eyes adjusted to the dark world and I was able to take in this old mine that is such an important site for our resident hibernating bat populations and, hopefully, a location that can play a critical role in its recovery.

White Nose Syndrome (WNS), the fungal infection that is devastating cave and mine bats acrossNorth America, took its toll at Hibernia Mine. Pre-WNS counts regularly found 30,000 bats in Hibernia. The population crashed over the winter of 2008, when 90% of the bats in the mine died and, with subsequent deaths during winter ’09 and ‘10, now only 1,500 call this place home. The remains of thousands of dead bats, scattered on the floor throughout the mine, bear sad testament to the losses seen by this place since WNS emerged as a mass killer of bats.

On this particular Sunday, we went into the mine to help John Gumbs with a research study that seeks to shed light – literally and figuratively – on the progression of the fungus that causes WNS and, in so doing, help develop a cure, a barrier, or at least a better model for the recovery of the population.

Walking deep into the mine with John and Mackenzie, it was hard to get a true feeling of the earth pressing down on top of you. The main shaft we were walking through was wide and tall. Parallel tracks down the shaft were evidence of the presence of a steam train that had hauled ore from the mine during its peak production phase in the late 1800’s. Traces of soot from the underground steam trains mark the ceiling of the shaft. It was only when we went deeper into the mine, and explored a partially collapsed shaft with boulders as large as VW vans hanging above our heads, that a sense of the weight of the place became apparent.

But we were not there to explore. We were there to work. The purpose of our trip into the mine was to take photographs of bats under UV light to record the level of fluorescence on the bats’ wings.

John Gumbs and Mitzi Kaiura from Bat Research Center have pioneered a new research tool that uses UV light to visualize the tissue reaction caused by the fungus most likely causing WNS, Geomyces destructans (Gd), before other clinical signs are apparent. This research will expand biologists’ knowledge of the disease and the timeline associated with its impact on the hibernating population. You can read more about the Bat Research Center’s project and goals here.

To help John, we collected a small number of hibernating bats from the walls and roof of the main shaft. Each bat was plucked off the wall and placed into a small container with air holes. John set up a camera midway in the shaft. The collected bats were carried to the camera and gently laid on a cloth-covered black box, extending their wings to fill the camera’s viewfinder. Once the bat’s wing was positioned fully in the viewfinder, off went our headlights and on came the UV light which showed the bat in, no pun intended, a whole new light. Their teeth glowed in the UV light, their feet glowed likewise and their wings showed speckles, dapples or entire washes of fluorescence – possibly indicative of the progression of the disease. John hopes to develop a multi-year photo documentation of all phases of the Gd disease progression during hibernation and afterwards illustrate a link between this fluorescence and Gd.

Time flowed in a strange way inside the mine as we walked along the shaft examining clusters of hibernating bats and choosing some to be photographed. Time was told only by the cold seeping in through our boots or along our fingers. In the darkness, time seemed to be totally absent and the ever-encroaching cold was the trigger to send us up and out of the mine.

On finally emerging into a sunny Sunday, following the reverse maneuver through the opening in the gate, it was like departing one world – dark, damp, silent and cool – for another full of sound, light and color. Hikers passing by wearing shorts on this Indian summer day must have wondered at the winter-clad people emerging blinking into daylight!

A few things struck me about this adventure, not least of which is that I spend way too much time in the office. But the most important thing was the ingenuity and hard work of the people focused on protecting our bat population from extinction. John Gumbs, through his work, has developed photography methods to track the disease, engineered special tools to increase his efficiency and is now pioneering a method to cool bats into hibernation as a way to re-introduce them to their natural hibernacula, all on his own initiative and without any funding. We support John’s efforts and if you would like to also support his efforts or learn more about his work, please see our partner page.

The fight to save our bats from extinction continues in the cold, quiet darkness of Hibernia Mine and if passionate, innovative people like John Gumbs from Bat Research Center; Mick Valent from the state’s Endangered Species Program; Jackie Kashmer whose rehabilitation work we profiled recently; and Mackenzie Hall from Conserve Wildlife Foundation, are focused on this, we can hold out some hope for our precious and valuable bats.

Discover more from Conserve Wildlife Foundation of NJ

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Comment

Hey John! Great work you’re all doing to help these bats. Thanks.

Comments are closed.