Malaclemys terrapin terrapin

Type: reptile

Status: special concern

Species Guide

Northern diamondback terrapin

Malaclemys terrapin terrapin

Species Type: reptile

Conservation Status: special concern

Key Feature

Only turtle that inhabits coastal marshes with brackish water (mix of salt and fresh water) for their entire life.

Identification

The northern diamondback terrapin is a medium-sized turtle that varies in length from only 4 to 5.5” in males to 6 to 9” in females. Females have a short, narrow tail while males have a relatively long, thick tail. Terrapin coloration varies highly between individuals, but all have a gray, brown, or black carapace (top of shell) and a lighter plastron (bottom of shell), which is a greenish-yellow. The skin is light to dark gray with black spots and other dark markings. Both sexes have a light colored upper mandible. They are named for their diamond shaped pattern on their carapace.

Distribution & Habitat

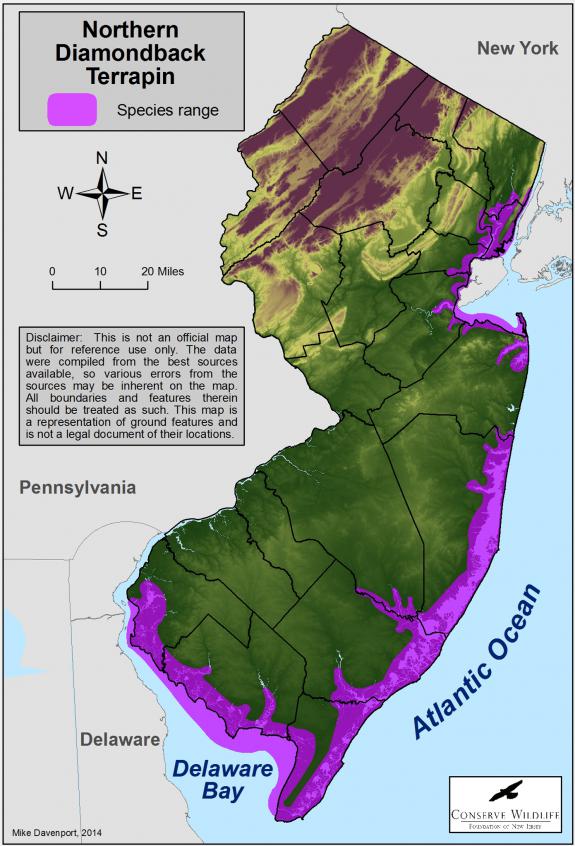

Northern diamondback terrapins exclusively inhabit coastal salt marshes, estuaries, tidal creeks and ditches with brackish water (a mix of both salt and freshwater) which is bordered by spartina grass. They are the only turtle in the world that is specially adapted to spend its entire life in this type of water. Studies have shown that terrapins exhibit a high level of site fidelity or they return to the same territory every year. They also have a very small home range and some occupy the same small creeks year after year. Northern diamondbacks range from Cape Cod, Mass. to Cape Hatteras, N.C.

There are 6 other subspecies of terrapins the Carolinan Diamondback Terrapin (M.t. centrata), the Florida East Coast Diamondback Terrapin (M.t. tequesta), the Mangrove Diamondback Terrapin (M.t. rhizophorarum), the Ornate Diamondback Terrapin (M.t. macrospilota), the Mississippi Diamondback Terrapin (M.t. pileata) and the Texas Diamondback Terrapin (M.t. littoralis). The species ranges from New England south to Florida and into Texas along the Gulf of Mexico.

Diet

Adult terrapins primarily eat mollusks and crustaceans, including snails, fiddler crabs, and mussels. They also eat blue crabs, green crabs, marine worms, fish, and carrion. Terrapins are more active during high tide, or when the marsh is often flooded.

Life Cycle

Terrapins are cold-blooded or ectothermic. They hibernate during the winter and bury themselves at the bottom of or in the muddy banks of open water bays, creeks and ditches. They always have some mud covering them. Adult terrapins mate in early spring. Females lay clutches of 8-12 eggs from early June into mid-July in sandy beaches and other upland gravel areas that are above the high tide line. The eggs hatch in 61-104 days. The warmer the soil, the faster they hatch. The sex of hatchlings is determined by the temperature of the soil, the warmer the soil, the more females that are produced. This is known as temperature dependent sex determination (TSD). Only around 1-3% of the eggs laid actually produce a hatchling, and success rates of young reaching adulthood is also low. Hatchlings sometimes overwinter in nests (those that were laid later in the year) and emerge the next year (in April). After hatching they immediately head for vegetation, which helps provide cover and protection from predators, like gulls and crows. Occasionally hatchlings wind up in storm drains, where many die since they cannot escape. Males reach maturity at 5-8 years in age or when they are around 3-3.5″ in length, while females do not reach sexual maturity until they are approximately 9-10 years in age or are 6.5″ in length and weigh 2.3lbs.

Current Threats, Status, and Conservation

Terrapins were once very common and were used as a main food source of protein by Native Americans and then European settlers. From the mid-1800s early 1900s they were hunted so extensively that they almost faced extinction. Terrapin stew was a popular delicacy in the U.S. and terrapins were exported to several European countries. In the late 19th century, 400,000 lbs were harvested annually (True 1887). By 1920, their population dwindled and only 823 lbs were harvested in one year on the Chesapeake Bay and cost $125/dozen. In the 1920s, the use of terrapins for food dropped in popularity. This allowed the population to slightly recover and avoid extinction.

In 2001, a status review of reptiles in New Jersey recommended that the Northern diamondback terrapin be listed as a species of special concern in New Jersey. The listing as special concern “warrants special attention because of some evidence of decline” (NJ ENSP-Species Status Listing) and little is known about their actual population status in New Jersey. However, terrapins were still harvested in New Jersey and the total harvested annually was not known. The open season for terrapins was from November 1 to March 31 (NJ Division of Fish and Wildlife – Bureau of Marine Fisheries). Because they were considered a “Game” species subject to harvest, the Special Concern designation was never officially applied to the species.

In 2014 and 2015, NJDEP halted their harvest through an administrative order. This came after a federal CITES investigation revealed that 3,500 were harvested from NJ waters in 2014 and that many were likely to be harvested illegally. It was believed that by restricting the harvest to “by hand” with no traps, nets or drags, that the harvest would be minimal in NJ, but with growing demand and markets in Asia it’s apparent that they were being exploited. The administrative orders were a good first step to protect terrapins but they needed to be removed from the “game” list.

In 2015 and 2016 legislation was drafted and voted on by the NJ law makers to remove terrapins from the game list. In July 2016 Gov. Chris Christie signed the legislation and terrapins are now considered a non-game species with no hunting season.

In 2016, another status review recommended a Special Concern status for this species within the state, but no formal rule proposal was adopted until January 2025.

Today several major threats still threaten the survival of terrapins in New Jersey. Habitat loss, mortality from being drowned in crab traps, road mortality, and illegal collection all pose major threats to the health of the population. Hundreds of acres of terrapin habitat has been destroyed or altered by coastal development. Bulkheads restrict their natural movement and mosquito ditches have altered the tidal flow on our salt marshes. Roads all throughout the coastal area bisect terrapin habitat. Females are drawn to road shoulders because they mimic natural nest sites and in turn many are hit-by-car and killed each year while attempting to nest. High levels of contaminants have been found in the livers of terrapins. It is not clear how exactly they are affected by contaminants. Studies have shown that crab traps can capture and kill between 15-78% of a local population in one year (Roosenburg et al. 1997). Old, abandoned “ghost” traps create death traps for juvenile and male terrapins for years. It is unknown how many die from “ghost” traps. Human development has created ideal conditions for increased numbers of raccoons and skunks in coastal areas and increased predation of terrapin nests. One study on Little Beach Island found that between 51% to 71% of nests were predated from egg laying to hatching (Burger 1977).

HOW TO HELP

The New Jersey Fish and Wildlife, Endangered and Nongame Species Program would like for individuals to report their sightings of terrapins. Record the date, time, location, and condition of the animal and submit the information by submitting a Wildlife Sighting Report Form. The information will be entered into the state’s natural heritage program, commonly referred to as Biotics. Biologists map the sighting and the resulting maps allow state, county, municipal, and private agencies to identify important wildlife habitats and protect them in a variety of ways. This information assists in preserving wildlife habitat remaining in New Jersey.

References

- Avissar, Naomi G. 2006. Changes in Population Structure of Diamondback Terrapins (Malaclemys terrapin terrapin) in a Previously Surveyed Creek in Southern New Jersey. Chelonian Conservation and Biology, Volume 5, Number 1. 154-159

- Brennessel, B. 2006. Diamonds in the Marsh: A Natural History of the Diamondback Terrapin. University Press of New England, Lebanon, NH.

- Burger, J. 1977. Determinants of hatching success in the diamondback terrapin, Malaclemys terrapin. American Midland Naturalist 97:444-464.

- NJ Division of Fish and Wildlife – http://www.state.nj.us/dep/fgw/pdf/2010/comregs10.pdf

- Roosenburg, W. M., W. Cresko, M. Modesitte, and M. B. Robbins. 1997. Diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin) mortality in crab pots. Conservation Biology 11:1166-1172.

- True, F. W. 1887. The turtle and terrapin fisheries, pp. 493–503. In: G.B. Goode et al. (eds.), The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States. Section 5, volume 2, part XIX. U.S. Commission on Fisheries, Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

Scientific Classification

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Reptilia

- Order: Testudines

- Family: Cryptodira

- Genus: Malaclemys

- Species: M. terrapin terrapin