Ambystoma maculatum

Type: amphibian

Status: special concern

Species Guide

Spotted salamander

Ambystoma maculatum

Species Type: amphibian

Conservation Status: special concern

IDENTIFICATION

The spotted salamander (Ambystoma maculatum) is a large salamander, ranging between 6 and 9½ inches. Its body is stout and broadly rounded with strong legs. Females are slightly larger than males. The adult form is colored black, gray or dark brown with a gray underside. The larvae are olive colored.

It gets its name from two characteristic rows of large spots located dorso-laterally. There are between 24-50 yellow or orange colored spots, irregularly arranged from head to tail. These brightly colored spots act as a warning mechanism to predators, warning of the salamanders’ toxic, milky substance secreted from glands along the back and tail. Along the side are also 12 costal grooves.

Distribution & Habitat

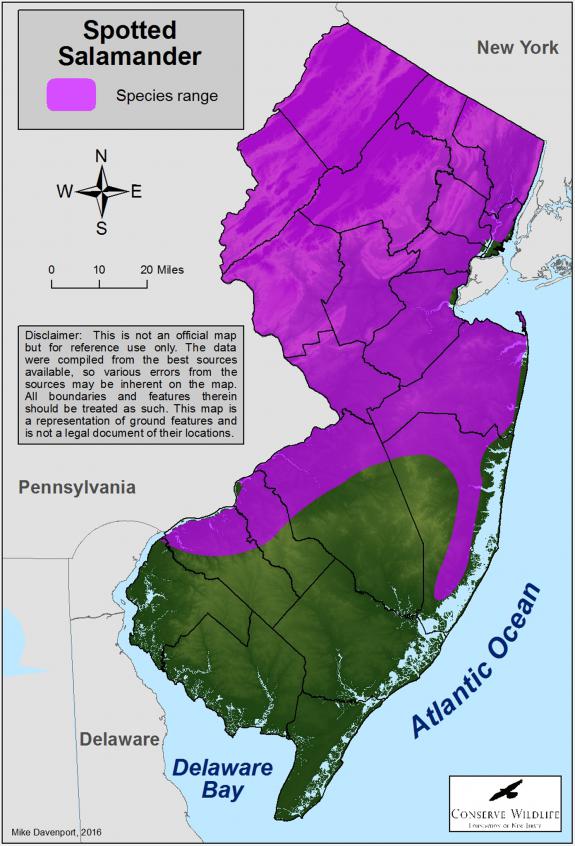

This species ranges throughout eastern North America, from Nova Scotia and the Gaspé Peninsula, west to Lake Superior and south towards southern Georgia and Eastern Texas. It can be found throughout northern and central New Jersey, however is absent from most of the southern portion of the state.

The spotted salamander is usually found in deciduous forests along rivers. However, it may occur in other types of forests so long as the climate is damp enough and suitable areas for breeding occur. This species is fossorial, meaning it burrows in the ground and are rarely seen except when making their way to breeding grounds. Occasionally, adults can also be found hiding in leaf litter or under logs.

Diet

In both larval and adult forms, salamanders are predators. As aquatic larvae, it is a vicious generalist, eating any small animals it can catch. Small insects, daphnia and fairy shrimp include some smaller prey items, but as the larvae grows, it will prey upon larger insects, amphipods, isopods, tadpoles and even other salamander larvae. In times of overcrowding, it may even become cannibalistic, preying upon others of its own species.

The adults use a sticky tongue to catch their prey. It is primarily an invertivore, consuming a variety of invertebrates that can commonly be found on the forest floor. This includes a wide array of insects, snails and slugs, millipedes, centipedes, spiders, and worms. Occasionally, it is known to consume smaller salamanders.

Life Cycle

These early spring breeders are known to make mass migrations to breed. Breeding occurs after the first heavy rain that follows the thawing of winter snow. Breeding occurs at the pond sites, and males may compete for females by shoving one another out of the way. Fertilization happens internally, as females select spermatophores deposited by males. Males can lay several spermatophores, fertilizing several females, and females in turn can be fertilized by several males.

Eggs are deposited as large masses in shallow freshwater ponds that lack predatory fish, often in temporary or vernal pools. Females attempt to lay their clutches in protective areas such as on submerged vegetation and cover with them with a thick layer of jelly which protects against some predators and dehydration. This is the extent of female parental investment; males provide none. This species has a longer incubation period than most other salamanders. The aquatic larvae hatch between four to eight weeks, equiped with gills and a strong tail for swimming, having only weak front legs and entirely lacking the back pair.

In two to four months, the larvae metamorphose into terrestrial juveniles with four strong legs and lungs. The time it takes for a juvenile to mature varies, mostly influenced by temperature. In warmer southern parts of its range, it will take two to three years to become reproductively mature. In cooler, northern areas, however, it can take up to seven years. The vast majority of spotted salamanders die before they metamorphose, due to disease, predation, or the drying of their pond. Survival greatly increases as the salamanders surpass this tenuous stage of life, and once transformed, typically live twenty years.

Current Threats, Status, and Conservation

The spotted salamander requires two habitats to complete its life cycle. Therefore, threats to both forest habitat occupied by adults and breeding pools threaten its survival. This is true for many species of Ambystoma. Reliance on specialized breeding habitat has resulted in salamanders being especially susceptible to negative impacts from habitat alterations.

A major threat is general habitat loss and fragmentation caused by human actions. Habitat loss not only can eliminate necessary habitat, but also causes populations to become smaller and isolated, reducing gene flow, genetic diversity, and causing an inbreeding depression, all which make subpopulations more susceptible to local extinctions. Additionally, roads which can create divides between habitats can add to adult mortality from vehicles. In several locations where salamanders are known to make their mass migrations to breeding grounds, roads will be closed to allow their safe crossing. People can attend these crossings to catch a glimpse of this otherwise seldom seen animal.

Degradation of its forest habitat from activities such as timbering that reduce canopy cover is another threat that it faces. Acidification of freshwater ponds negatively impacts embryos, reducing larval success. Road salts and pesticides pollute ponds and have negative effects that decrease larval survival and the existence of this species. The addition of harmful anthropogenic influences to larval habitat increases the already high mortality rate of its larval stage.

In 2016, the New Jersey Endangered and Nongame Advisory Committee recommended a Special Concern status for this species within the state and the status update was adopted in January 2025.

HOW TO HELP

The Endangered and Nongame Species Program would like for individuals to report their sightings of spotted salamanders. Record the date, time, location, and condition of the animal and submit the information by submitting a Sighting Report Form. The information will be entered into the state’s natural heritage program, commonly referred to as Biotics. Biologists map the sighting and the resulting maps “allow state, county, municipal, and private agencies to identify important wildlife habitats and protect them in a variety of ways. This information is used to regulate land-use within the state and assists in preserving endangered and threatened species habitat remaining in New Jersey.”

References

- Savannah River Ecology Laboratory

- Animal Diversity Web- University of Michigan

- IUCN Red List

- Amphibia Web

- NJDEP Field Guide

Text written by Kendall Miller in 2016.

Scientific Classification

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Amphibia

- Order: Caudata

- Family: Ambystomatidae

- Genus: Ambystoma

- Species: A. maculatum