Calidris canutus

Type: bird

Status: endangered

Species Guide

Red knot

Calidris canutus

Species Type: bird

Conservation Status: endangered

Federal Status: threatened

Breeding Status: non breeding

Identification

During migration to and from its breeding and wintering grounds, the red knot rests and refuels here in New Jersey. It arrives here in May in its breeding plumage and again in September while molting into its non-breeding plumage. In its breeding plumage (May-August) the red knot has a distinctive breast feathers. They are distinctively colored a brilliant rusty red. This rusty red color extends up the neck and around the eyes. It bleeds somewhat into the patterned black, brown, gray and white colorations on the wings and back. The rump is whitish. The knot has a short, straight black bill. In its breeding plumage the legs are dark brown to black. Some adults arrive in the middle of their molt showing various amounts of the non-breeding plumage. Non-breeding plumage is typically seen between September and April, and is a washed-out gray look with scaly white feather edgings, whitish flanks with dark barring. The legs turn a greenish color. Juveniles are primarily gray, with a scaly pattern on the wings and dull yellow-olive legs.

Distribution & Habitat

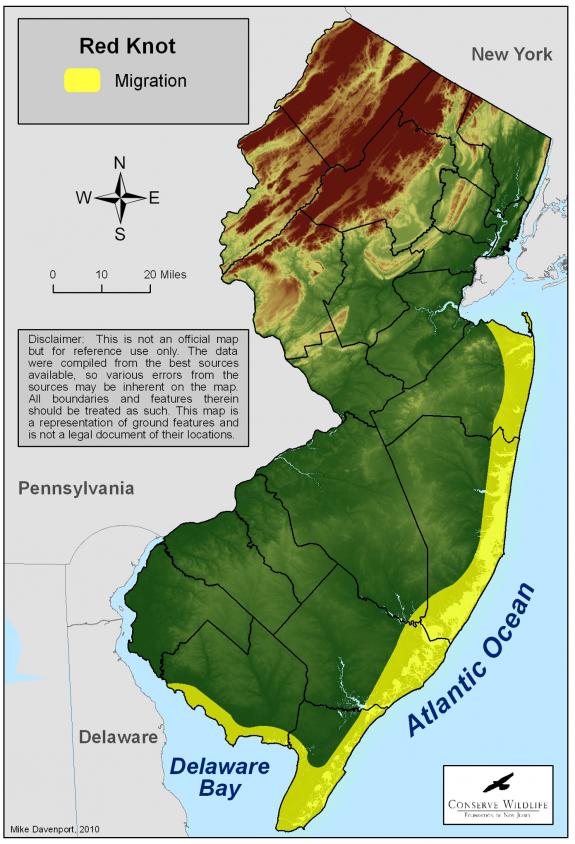

Red knots begin arriving in New Jersey in early May. They continue to arrive in Delaware Bay where the population peaks to around 20,000 birds by mid-May. The average peak number of knots on Delaware Bay has dropped significantly since the late 1990s, generally attributed to a decline in their main food, horseshoe crab eggs. Red knots range from Fortescue south to Cape May in New Jersey and from Port Mahon south to Cape Henlopen in Delaware (Clark et. al. 1993). Major concentrations of knots may be found at Reed’s Beach, Cook’s Beach, Norbury’s Landing, and Fortescue.

Red knots on Delaware Bay depend primarily on horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus) eggs for food, and Delaware Bay hosts the largest spawning concentration of horseshoe crabs on the East Coast. Knots concentrate in high numbers in areas of dense horseshoe crab spawning, generally beaches that have gentle slopes with little wave action. When not actively feeding, knots may roost on the high portions of sandy beaches along Delaware Bay, but usually fly to roosts on the Atlantic side of the Cape May peninsula. Roost areas may be the long sandy spits at ocean inlets, as well as the numerous marsh islands scattered between North Wildwood and Sea Isle City. Birds also roost on sandy beaches and spits on Egg Island and Fortescue on Delaware Bay.

In the Arctic, nesting red knots use a distinctive habitat type. Vast areas of low tundra that are sparsely vegetated are preferred by knots to nest. These areas remain mostly covered in snow until mid-June. Birds must build nests in areas swept free of snow by prevailing northeasterly winds. Foraging habitat often consists of extensive isolated or wetlands that are dominated by sedges.

On southbound migrations, shorebirds, and their foods, are more dispersed across marsh flats and sandy washes. In New Jersey, many knots can be found along the Atlantic coastal beaches in August and September. They feed and roost there with several other species of shorebirds as they slowly make their way to wintering areas in southern South America. Occasionally large concentrations can be found anywhere from the Little Egg Harbor Inlet south to Wildwood Crest.

In their wintering areas, knots primarily occur on large tidal flats. Red knots roost in expansive sand flats that are only infrequently flooded by tides. Most of the wintering population occurs in Bahia Lomas, Tierra del Fuego, Chile. Birds there feed on a large sandy flat five miles wide and more than 40 miles long (Niles et al. 2001b). They roost along the water’s edge.

Diet

When red knots arrive in New Jersey from their wintering areas they have little to no fat reserves remaining. Knots burn all of these fat reserves and sometimes even muscle to reach the Delaware Bay. Their migration is timed to take advantage of the concentration of spawning of horseshoe crabs, whose eggs provide a rich food source. Knots gorge themselves on the crab eggs to build up their fat reserves. These fat reserves will allow them to fly directly to their breeding grounds in the Arctic. Most double their weight in Delaware Bay, from only 110 grams to 185-220 grams before leaving and continuing their migration to breeding grounds in the high arctic. If some individuals do not gain enough weight or build up enough fat, then they may not reach their breeding grounds with enough reserves to survive and lay eggs.

During spring migration knots primarily eat the readily available and energy-rich horseshoe crab eggs. They also eat mussel spat (juvenile mussels) along Atlantic coastal marshes and beaches, when they are available in the proper size.

In the Arctic, knots rely on some of their fat reserves when they first arrive. The tundra may still be frozen with no available food. When the temperature warms, the knots eat insects, primarily mosquito larvae and spiders.

During fall migration they eat tiny mussels, clams, and marine worms. On their wintering grounds, in Chile, they primarily eat tiny mussels (spat) and clams.

Life Cycle

With fat reserves built up on Delaware Bay knots leave New Jersey in the first week of June. They arrive on their breeding grounds in the Arctic tundra one week later. Usually at this time the tundra is always covered with snow.

They nest on the ground in barren and sparsely vegetated areas free of snow cover from the prevailing north winds. Their nest bowls are lined with lichens and dead leaves of dryas, a grass-like plant. Nesting in these areas helps reduce the chance of predation from Arctic foxes, which prefer more vegetated areas of the tundra.

They establish small territories close to wetland areas where they feed. Even though their nest sites are isolated they can still fall prey to a variety of predators. In many cases the amount of predator pressure on knots relies heavily on the amount of other available prey in the Arctic, like lemmings.

Knots lay a clutch of four small olive colored and brown marked eggs that are incubated for 21 to 23 days. When the young hatch they are precocial (independent). They are born with downy feathers and can feed shortly after hatching. Within 48 hours from hatching the young follow the male to wetland areas to feed. The tiny (3 in. tall) hatchlings may travel more than a mile through rocky and barren tundra to reach suitable foraging areas.

Current Threats, Status, and Conservation

The first comprehensive surveys of red knots on the Delaware Bay began in 1982. Since 1986, the surveys have been conducted annually by the ENSP’s Kathleen Clark. This survey is one of the longest running surveys of shorebirds in North America. During the study period red knot numbers have fallen dramatically. High counts of more than 90,000 birds in the 1980s have fallen to about 13,000 birds in 2007. Surveys in the Tierra del Fuego wintering area and Delaware Bay suggest the red knot population has stabilized at a low level. Additional catastrophic events could damage the species irreversibly. Conservation action in New Jersey, the 2007 moratorium on horseshoe crab harvest, is expected to improve conditions at the Delaware Bay stopover and help the population maximize nesting success in the Arctic.

Due to the severe declines in Delaware Bay stopover and wintering grounds, and the threats of declining food resources, the red knot was listed as threatened in New Jersey in 1999, and it was identified as a candidate for listing by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 2007. Also in 2007, the harvest of horseshoe crabs in New Jersey was banned to increase the crab eggs available to knots. To help protect red knots and other shorebirds along Delaware Bay many beaches are closed to the public from the beginning of May into June. These beach closures minimize disturbance to knots so they are not disturbed while feeding. Volunteer “shorebird stewards” educate the public at beaches during spring migration to educate them about the importance of red knots and what is being done to protect them. The red knot was reclassified from threatened to endangered in New Jersey in 2012.

References

- Beans, B. E. and Niles, L. 2003. Endangered and Threatened Wildlife of New Jersey.

- Clark, K.E., L.J. Niles, and J. Burger. 1993. Abundance and distribution of migratory shorebirds in Delaware Bay, NJ. Condor 95:694-705.

- Niles, L.J., K. Ross, and R.I.G. Morrison. 2001b. Survey of red knots in Tierra del Fuego (abstract). Wader Study Group Bull. 95 (August 2001):10.

Edited and updated in 2010 by Kathy Clark & Ben Wurst. Updated in 2012 by Michael J. Davenport.

Scientific Classification

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Aves

- Order: Charadriiformes

- Family: Scolopacidae

- Genus: Calidris

- Species: C. canutus