Charadrius melodus

Type: bird

Status: endangered

Species Guide

Piping plover

Charadrius melodus

Species Type: bird

Conservation Status: endangered

Federal Status: threatened

Identification

The piping plover is a small shorebird with a black neck band and a black bar across the forehead. The upperparts are light sandy-brown and the underparts are white, providing camouflage against sandy beach backgrounds. The legs are bright orange and, in breeding plumage, the bill is also orange with a black tip. Although males and females are similar in appearance, males typically have darker, more extensive neck bands. The call of the piping plover is a ventriloquist-like peep-lo which is often heard before the bird is seen.

Juvenile and winter-plumage adults are similar in appearance. Both lack the black neck and forehead bands characteristic of breeding adults. Rather, there is a pale band around the neck. The bill is solid black and the legs are pale yellow.

Distribution & Habitat

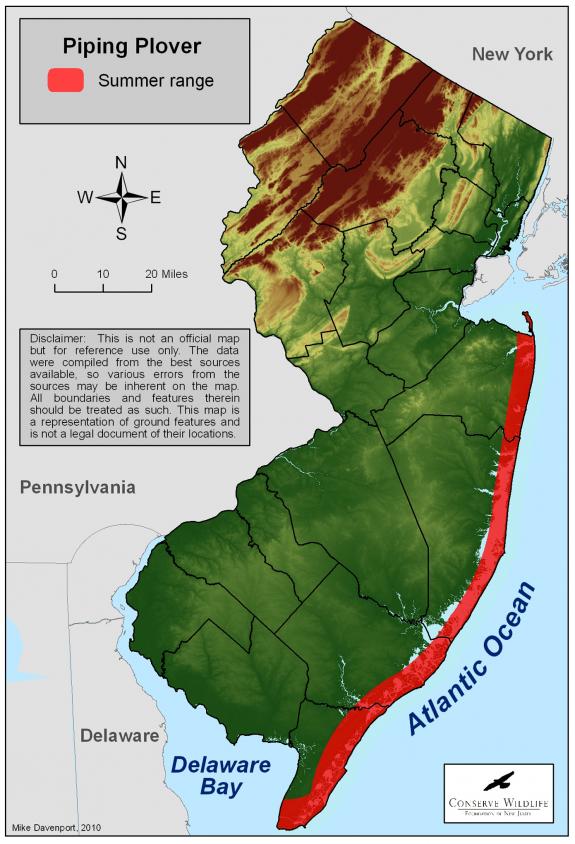

In New Jersey, piping plovers breed on Atlantic Coast beaches from Sandy Hook to Cape May. Migrant plovers are present from early March to mid-April and from mid-July to late September. Females depart first during fall migration from their breeding grounds, followed by males, then juveniles.

Piping plovers inhabit oceanfront beaches and barrier islands, typically nesting on the stretch of beach between the dunes and the high-tide line. Nests are often located in flat areas with shell fragments and sparse vegetation. The coloration of piping plovers and their eggs blend in remarkably with sand and broken pieces of shell. Plovers may nest in sparse vegetation, as it provides cover against predators and the elements. However, areas with dense vegetation, such as dunes, are avoided by nesting plovers, since these sites provide cover for predators.

Diet

The diet of the piping plover is dominated by marine invertebrates, including marine worms, small crustaceans, and mollusks. In addition, insects, such as beetles and larvae, are consumed. Adult piping plovers feed primarily during the day, but may also forage at night. Foraging activity peaks during the hours before and after low tide, when intertidal areas are exposed.

Life Cycle

During late March and April, piping plovers arrive at New Jersey’s barrier islands and beaches. Males establish territories upon arrival, performing aerial displays and calling to mark their boundaries and attract mates. The male digs numerous nests, also called scrapes throughout his territory, kicking sand, stones, and shells aside during the excavation. Piping plovers are usually monogamous during each nesting season, but may pair with different mates in successive years. Plovers exhibit fidelity to nesting sites, and may return to a previously successful area in subsequent years.

During April and May, piping plovers lay 3 to 4 sand-colored eggs which both parents will help to incubate for about 27 days. If a nest is destroyed early in the season by floods or predators, the pair usually lays another nest, sometimes several in a season, but typically no later than the end of June. The chicks, which are tiny, white, and downy, leave the nest within a few hours of hatching. Able to walk, the chicks follow their parents, pecking and running in search of food. When predators or intruders come close, piping plover chicks squat motionless on the sand while the parents attempt to attract the attention of the intruders, often by pretending to have a broken wing. In areas where several plovers nest in close proximity, neighboring pairs may assist one another in luring predators away.

Both the male and female care for the chicks for about 3 to 4 weeks. The young, which are able to fly at 25 to 35 days, fledge from late June to mid-August. The juveniles can breed the following year, but many do not until their second year. Often young will return to their natal area to nest.

Current Threats, Status, and Conservation

In 1984, the piping plover was listed as an endangered species in New Jersey. In 1986, the Atlantic Coast piping plover population was listed as threatened in the US. Active monitoring and management of the birds by biologists are integral parts of federal recovery efforts.

The piping plover remains one of New Jersey’s most endangered species. The threats that it faces, including increased beach recreation and predation, continue to act as serious impediments to the recovery of this species. Without intense protection and management, it is unlikely that the piping plover would survive in New Jersey.

Human activity, coastal development, and “hardening” of our coast through the construction of jetties and seawalls threaten the piping plover in New Jersey by reducing suitable nesting habitat. Human activity near nesting sites can disturb nesting plovers, flushing adults and leaving chicks vulnerable to predators. In addition, people may inadvertently trample the camouflaged eggs or chicks.

As plovers arrive in New Jersey in spring, biologists protect the nesting areas with fence and restricted area signs. Once biologists locate nests they typically enclose them in a special cage that keeps predators out. Additionally, educational signage and brochures are easily visible to the public. Seasonal biologists, interns, and volunteers also regularly patrol the nesting sites to help beachgoers understand why access to some portions of the beach and certain activities, such as dog walking, are restricted to protect piping plovers.

New Jersey’s piping plovers only require a small portion of our beaches to breed, but we must also do our part to “share the shore” if they are to survive. Learn about the work being done to research and protect NJ’s beach nesting birds at our Beach Nesting Birds Project webpage.

References

Beans, B. E. and Niles, L. 2003. Endangered and Threatened Wildlife of New Jersey.

Scientific Classification

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Aves

- Order: Charadriiformes

- Family: Charadriidae

- Genus: Charadrius

- Species: C. melodus