Circus cyaneus

Type: bird

Status: endangered

Species Guide

Northern harrier

Circus cyaneus

Species Type: bird

Conservation Status: endangered

Identification

Northern harriers are often seen flying low over the open coastal marshes of New Jersey. They are a medium to large-sized hawk. They have a white “rump patch” that located above the tail. They often fly very low and the position of their wings look like a shallow “V.” It has owl-like facial disk that aids it in detecting prey in tall grass or low-light conditions. It concentrates sound towards the ears. Adult northern harriers are sexually dimorphic, or the female and male look different, in both plumage and size. The males are smaller and have a slate gray color above and white below. They have contrasting black wingtips and a black back edge on the wing. The male’s white breast has varying amounts of light rufous (rusty) spotting. The female is larger and is brown above and buff colored below. They have brown vertical streaking on the chest and belly. The underwing of the female is dark and the black wingtips are masked. On all harriers, the white “rump patch” is a key in-flight field mark. Adult harriers have lemon yellow eyes. The legs are long and yellow. The cere (the fleshy area behind the base of the bill) is yellow. The bill is black.

Juvenile northern harriers are extremely similar in appearance to adult females. Juveniles are slightly darker than adult females. They have a cinnamon wash to the underside that is faintly streaked. Juvenile males are born with grayish eyes that turn to a lemon-yellow by their first winter. Juvenile females have dark brown eyes that take at least two years to appear yellow.

Northern harriers employ several different calls. A chirp-like call between male and female is given during food exchange or on the ground during mating. This call is also exchanged between females and nestlings. The alarm call of harriers consists of a series of kaks when a predator or intruder disturbs the nesting area. The male often calls with a high-pitched, gull-like whine during courtship and territorial display flights. A Northern harrier hunting low over a marsh is one of the most distinctive raptors in flight.

Distribution & Habitat

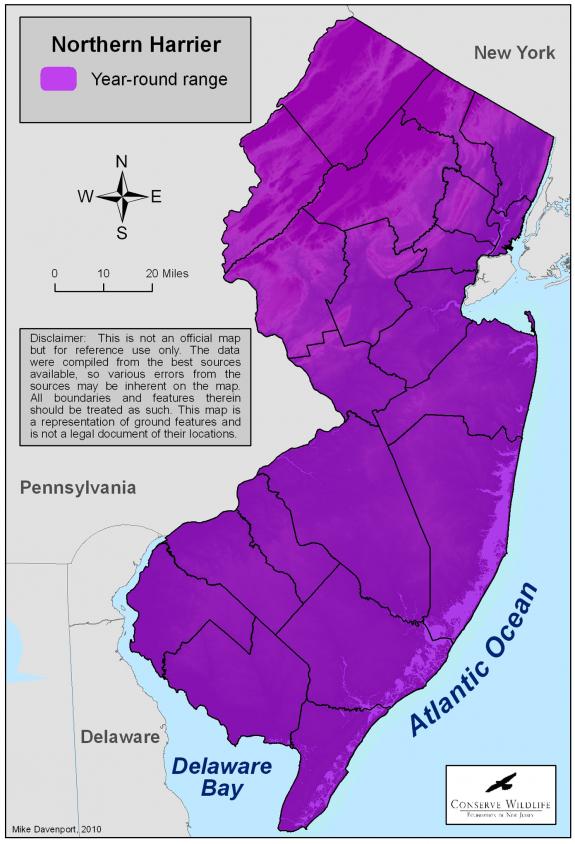

The Northern harrier ranges throughout most of North America. It breeds from Canada and Alaska south to California and Texas in the West and through the Mid-Atlantic States south to Virginia in the East. They winter throughout the contiguous United States south to Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean Islands, and sometimes northern South America.

Formerly known as the “marsh hawk,” the northern harrier inhabits open areas such as tidal marshes, emergent wetlands, fallow fields, grasslands, meadows, airports, and agricultural areas. Many nests in the state occur along the Delaware Bay shore in brackish or saline marshes. Within these areas, harriers nest in the high marsh areas that are usually drier than low marsh areas. High marsh is dominated by salt hay (Spartina patens), marsh elder (Iva frutescens) or reed grass (Phragmites communis). Harriers may also nest in freshwater tidal marshes. Inland nesting sites may be located in managed, fallow, or low-intensity agricultural fields that contain tall grasses and herbaceous vegetation.

Northern harriers forage over marshes, fields, bushes, and edges that contain low vegetation, often only 3 to 6 ft. high. Phragmites may be used for nesting but it offers poor foraging habitat for harriers. It forms very dense and almost impenetrable stands of the vegetation.

Male and female harriers are different in size and they exhibit sexual variation in diet and foraging habitat. During the nesting season, females typically hunt within the marsh. Males forage in the marsh and often seek prey along upland edges and fields. Males can fly long distances while foraging for prey. They have larger home ranges than females. Individuals occupy larger territories during the winter when food is scarce.

Northern harriers occupy similar habitats throughout the year. Communal winter roosts of harriers are located on the ground within drier portions of marshes or in grasslands. Roost sites can be readily recognized. They are usually littered with pellets, feathers, and excrement.

Diet

Harriers are opportunistic. Generally they eat whatever is most abundant or available during the differing seasons. They are known to eat small mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and insects. When prey numbers are down during unusually wet or cold weather in the breeding season the reproductive success of harriers is reduced.

In the summer months harriers mainly feed on the plentiful numbers of young songbirds, mammals, and reptiles and amphibians. In the winter their diet shifts to mainly small mammals, some birds, and carrion. Mammal prey includes voles, mice, shrews, rats, and rabbits.

Life Cycle

Courtship begins in late February and peaks in April. Males perform elaborate aerial courtship displays. They are meant to announce their presence in their territories and maintain pair bonds with a female. The male flies up over the marsh, pauses, then dives in steep.jpg’apid dives.

Male Northern harriers usually mate with one to two females. But when prey resources are abundant some males may mate with up to five females during the breeding season. Females construct nests on the ground. They use grasses, reeds, and sticks in their nests. Nests are prone to flooding and sometimes taller nests are built to avoid being lost. Female harriers lay between 4 to 6 eggs. Eggs are laid in two day cycles. The female incubates the eggs for 28 to 39 days. The young hatch asynchronously or the eggs hatch in the order that they were laid. This adaptation gives the older young a better chance at survival if food is scarce. The male provides most of the food during incubation and brooding. He drops the prey over the nest and sometimes the females flies up and catches the prey. When the young are two weeks old they begin to explore around the nest. At five weeks the young begin to fly. Several weeks later the young are completely independent and migrate south during the winter.

Current Threats, Status, and Conservation

Prior to the early 1900s, the Northern harrier was a common breeding species and winter resident within suitable habitat in the northeastern United States. Historic winter roosts in Hunterdon County, New Jersey, contained over 100 harriers. In the early 20th century, Northern harriers and most other raptors were commonly shot because of suspected predation on chickens, game birds, and waterfowl. The number of breeding harriers in New Jersey declined as early as the 1920s and continued into the 1940s.

The loss of open areas from reforestation and draining and filling of coastal marshes greatly reduced suitable habitat for harriers. Harrier declines coincided with the extensive dredging and filling of coastal wetlands in New Jersey from the mid-1950s to the mid-1970s.

Harriers were also affected by pollution. They experienced reduced reproduction rates during the 1950s and 1960s from contamination with the persistent pesticide DDT. DDT gets magnified in the food chain. It accumulates in top-level carnivores, such as raptors. DDT contamination inhibits calcium production and causes eggs to have abnormally thin shells. The thin egg shells break under the weight of the adult during incubation. The use of DDT was banned in 1972 and harrier populations began to gradually recover. Today harriers are still affected by residual components of DDT, DDE. Current contaminant levels in northern harriers remain unknown. Elevated levels of DDE have been documented in other raptors, including peregrine falcons and ospreys, nesting in marshes along the Delaware Bay coast.

The Northern harrier was listed as threatened in 1979 due to population declines and habitat loss. In 1984, the status of the harrier was upgraded to an endangered species. It was listed because of the limited population size, restricted range, sensitivity to disturbance, and the continued loss of suitable nesting habitat. In New Jersey, wintering populations of harriers are stable and the breeding population is considered to be endangered. During the 1980s, the breeding population in New Jersey was estimated at 40 to 50 pairs statewide, with 20 to 30 pairs in the Delaware Bay estuary (Dunne 1995).

References

Dunne, P. 1995. Northern Harrier. In Living Resources of the Delaware Estuary, ed. L.E. Dove and R.M. Nyman, 381-385. Philadelphia: Delaware Estuary Program.

Text derived from the book, Endangered and Threatened Wildlife of New Jersey. 2003. Originally written by Sherry Liguori. Originally edited by B.E. Beans & L. Niles. Edited and updated in 2010 by Ben Wurst.

Scientific Classification

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Aves

- Order: Falconiformes

- Family: Accipitridae

- Genus: Circus

- Species: C. cyaneus