Danaus plexippus

Type: invertebrate

Status: not ranked

Species Guide

Monarch

Danaus plexippus

Species Type: invertebrate

Conservation Status: not ranked

IDENTIFICATION

Monarch butterflies are most easily identified by their bright orange color with black and white markings. The body of the monarch is black. The wings are mostly orange with black veins running throughout. The outer edges of the wings have a thick black border. Within the black border are white spots. The white spots can range in size. At the upper corner of the top set of wings are orange spots. The undersides of the wings are an orange-brown color. The monarch has a wingspan between 3 1/2 and 4 inches.

Males and females can be told apart by looking at the top of their hind wings. Males have a black spot at the center of each hind wing, while the females do not. The spot is a scent gland that helps the males attract female mates. Another less accurate way to tell males from females is that the females usually have much thicker veins than the males.

Monarch butterfly caterpillars are also easy to identify. The caterpillars have many yellow, black and white bands. There are antenna-like appendages at each end of the caterpillar’s body.

Distribution & Habitat

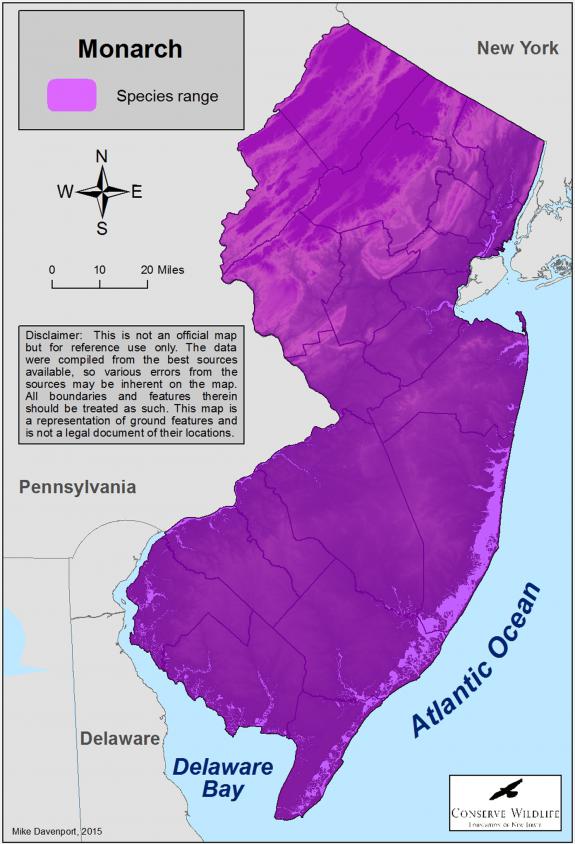

Wherever there is milkweed there are likely to be monarch butterflies. The monarch is widely distributed across North America, from Central America northwards to southern Canada, and from the Atlantic to the Pacific coasts. The majority of monarch butterflies in North America live east of the Rocky Mountains. In the early spring, they are first seen in Texas and the south. As spring turns to summer, they’re seen in more and more states and Canada. A much smaller population of monarch butterflies lives west of the Rocky Mountains. Instead of making the long journey between Mexico and Canada, the western monarchs only travel as far south as San Diego. Some monarchs live in California year-round and others spend summers as far north as British Columbia, Canada.

Monarch butterflies utilize different habitat in the warm months versus the cold months. In the spring, summer and early fall, they can be found wherever there is milkweed. Monarchs lay their eggs on milkweed. Monarchs cannot survive freezing temperatures, so they over-winter in the cool, high mountains of central Mexico and woodlands in central and southern California.

Diet

In their larval stage, monarch caterpillars feed almost exclusively on milkweed and as adults get their nutrients from the nectar of flowers. The monarch will always return to areas rich in milkweed to lay their eggs upon the plant. The milkweed they feed on as a caterpillar is actually a poisonous toxin and is stored in their bodies. This makes the monarch butterfly taste terrible to predators. Adult monarchs feed on nectar from a wide range of flowers.

Life Cycle

Most monarch butterflies do not live more than a few weeks. There are about 3 to 5 generations born each spring and summer and most of the offspring do not live beyond 5 weeks. The lone exception is the last generation born at the end of the summer.

The last generation of each year is the over-wintering generation that must make the journey back to Mexico. Rather than breeding immediately, the over-wintering monarchs fly back to Mexico and stay there until the following spring. In the early spring, they fly north to the southern United States and breed. Over-wintering monarch butterflies can live upwards of 8 months.

Over-wintering monarch butterflies in Mexico begin to make the journey north to the United States in early spring. Soon after they leave Mexico, pairs of monarchs mate. As they reach the southern United States, females will look for available milkweed plants to lay eggs.

The eggs hatch after approximately four days. The caterpillars are small and they grow many times their initial size over a two-week period. The caterpillars feed on the available milkweed plant. When they get big enough, each caterpillar forms a chrysalis and goes through metamorphosis.

The chrysalis protects the monarch as it is going through the major developmental change of turning from a caterpillar to a butterfly. The chrysalis is green with yellow spots. After another 2-week period, an adult butterfly will emerge from the chrysalis.

Current Threats, Status, and Conservation

There are some regions in which populations of monarchs are declining. It is predicted that one of the many effects of climate change will be wetter and colder winters. If they are dry, monarchs can survive below freezing temperatures, but if they get wet and the temperature drops, they will freeze to death. Because hundreds of millions of monarchs are located in such a small area in the Sierra Nevada of Mexico during the winter, a cold snap there could be devastating.

As the world warms, suitable habitat will begin to move northward resulting in a longer migration. This means the monarchs may be forced to adapt and produce another generation to reach further north. It is uncertain whether they will be able to do so. Therefore, few monarchs may be able to make the longer trip back to Mexico for winter.

Other threats to the monarch include habitat loss and loss of milkweed which they depend upon as larva to survive. Illegal logging and forest fragmentation are also problems for monarch wintering habitat. Herbicides are also a problem in that they kill milkweed plants.

In 2015, the New Jersey Endangered and Nongame Advisory Committee recommended a Special Concern status for this species within the state, but no formal rule proposal has been filed to date.

References

- National Wildlife Federation

- Defenders of Wildlife

- Nature Works

Text written by Michael Colella in 2015.

Scientific Classification

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Arthropoda

- Class: Insecta

- Order: Lepidoptera

- Family: Nymphalidae

- Genus: Danaus

- Species: D. plexippus