Dermochelys coriacea

Type: reptile

Status: endangered

Species Guide

Atlantic leatherback turtle

Dermochelys coriacea

Species Type: reptile

Conservation Status: endangered

Federal Status: endangered

Identification

The largest of all sea turtles, the leatherback is also one of the largest living reptiles in the world. Adults can attain a shell length of six and a half feet and weigh up to 2,000 pounds, but usually weigh between 638-1,298 pounds. It is easily distinguished by its black, leathery skin, huge, spindle- or barrel-shaped bodies and long flippers. The leatherback is the only sea turtle that lacks a hard, bony shell. Instead, the body is covered with a layer of rubbery skin that has seven longitudinal ridges (keels) on the back and five underneath. The dorsal or upper side of adults is predominantly black. Scattered white blotches arranged along the back become more numerous along the sides and even more so underneath, with the ventral side primarily whitish. Pinkish blotches on the neck, shoulders and groin intensify when the turtle is out of the water. The head and neck are black or dark brown, mottled with white or pink blotches. Each side of the upper jaw has a tooth-like cusp, giving the turtle a W-shaped beak. Paddle-like, clawless limbs are black with white margins, and may have white spots. Males can be distinguished from females by their much longer tails and narrower and less deep bodies.

Hatchlings are dark brown or black, with white or yellow carapace keels and flipper margins. They are only 2-3 inches in length. Their skin is covered with small scales that become thinner with each molt, which starts about three weeks after hatching. Claws may be visible in hatchlings, but they vanish in subadults and adults.

Distribution & Habitat

Unlike land turtles from which they evolved more than 150 million years ago, sea turtles spend almost their entire lives in the sea. When active, they often come to the surface to breathe, but can remain underwater for several hours at a time while resting. Leatherbacks can dive to more than 4,000 feet below sea level.

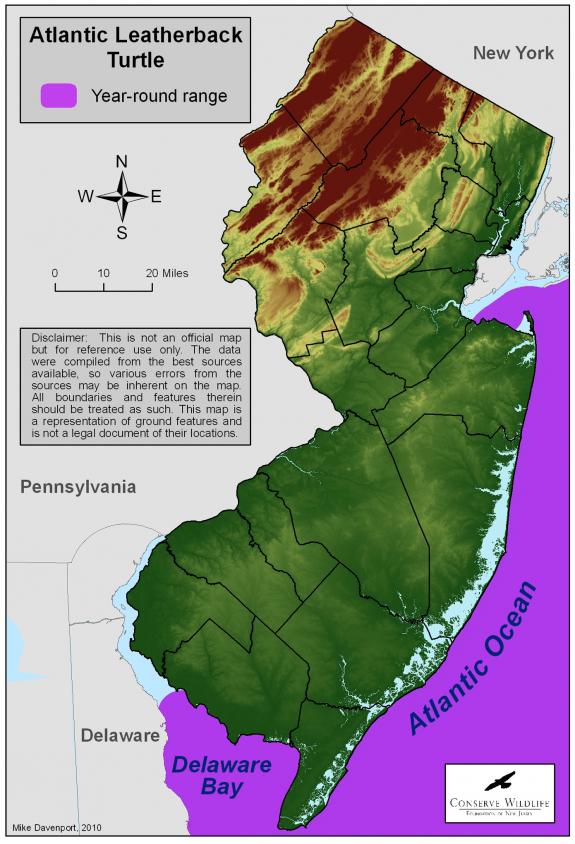

Though most sea turtles inhabit warm, tropical and subtropical waters, they migrate northward as water temperatures increase in the late spring and summer and remain in northern waters until late fall. From late May until November, New Jersey coastal waters provide important seasonal foraging habitat.

The most pelagic (open ocean) and wide ranging of sea turtles, the leatherback occurs within the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans. Within the Atlantic Ocean, they range from Newfoundland, Canada in the north to Argentina in the south. They are often found near the edge of the continental shelf, but in northern waters, they sometimes frequent shallow estuaries.

Nesting occurs on sandy, tropical beaches in places such as Florida, the Virgin Islands, Mexico, Costa Rica, Trinidad, Suriname, French Guiana, and Malaysia.

Diet

This sea turtle feeds primarily on jellyfish. They also feed on sea squirts and other soft-bodied animals. They have backward-facing spines within their throat which helps them hold onto and swallow their slippery, soft-bodied prey.

Life Cycle

Leatherback turtles mate within waters adjacent to nesting beaches and along their migration route. Females return to the beaches where they were born in order to nest every 2-3 years. The nesting season in the U.S. and Caribbean is between March and July. Nesting may occur several times during one season, typically at 8-12 day intervals. Each clutch consists of approximately 100 eggs. They nest primarily at night, often at high tide. Eggs hatch in about 2 months. Egg mortality may result from predation, beach erosion, invasion of clutches by plant roots, crushing by off-road vehicles, or flooding by sea water or excessive rainfall. The gender of hatchlings is affected by incubation temperature, with warmer temperatures resulting in a higher number of females and cooler temperatures producing mainly males. Of every thousand hatchlings, only a few are believed to survive to adulthood. Once they reach water, male hatchlings will never return to land while females will only do so to nest.

Leatherback turtles can tolerate colder water temperatures than other sea turtles. They have several adaptations, such as large body size and a thick layer of fat, which allow them to tolerate colder temperatures than other cold-blooded reptiles can. No other reptile, in fact, can remain active in the cold temperatures that leatherbacks do. They have been reported in waters which were 43ْْ F.

Besides being the largest and deepest diving of the sea turtles, leatherbacks are also the fastest swimmers. Aside from humans, the only predator of adult leatherback turtles is large sharks. Hatchlings may be preyed upon as soon as they leave their nest by raccoons, crabs, and birds. Once in the ocean, hatchlings may also be preyed upon by large fish.

Current Threats, Status, and Conservation

Leatherback turtle populations have been decimated by overharvesting of adults and eggs, loss of nesting habitat, interactions with fisheries, and entanglement or ingestion of marine debris. Their populations are currently a small fraction of their historical size. Because of this, leatherback turtles were listed as federally endangered in 1970. The leatherback turtle was listed as endangered by the state of New Jersey in 1979.

Leatherback turtles are currently faced with many threats such as the direct exploitation for food (including eggs), entanglement in fishing gear, oil spills, habitat degradation (such as beach development), beachfront lighting, ocean pollution (including marine debris, which may be ingested), and dredging (direct kills and injuries). Beach cleaning operations can destroy nests or produce tire ruts that inhibit movement of hatchlings to sea. Additional threats include predation and trampling of eggs and young by raccoons and feral mammals, crushing of eggs or young by vehicles or humans, collisions with boats and intentional attacks by fishermen. Long-term threats include sea level rise which, coupled with inland urbanization, may reduce available nesting beaches. Since sexual differentiation depends on incubation temperature, there is concern that global warming may result in an imbalance in the sex ratio.

Habitat use of sea turtles within New Jersey waters is poorly understood. The degree to which New Jersey plays a critical function in providing foraging habitat and migration corridors is unknown. Surveys are currently being conducted off the New Jersey coastline in order to determine where sea turtles are located, how many individuals are there, and during what time of year. Based on these findings, further knowledge regarding their habitat use in New Jersey waters may be gained and attention may then focus on protecting important habitats.

References

Text derived from the book, Endangered and Threatened Wildlife of New Jersey. 2003. Originally edited by Bruce E. Beans and Larry Niles. Edited and updated Michael J. Davenport in 2010.

Scientific Classification

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Sauropsida

- Order: Testudines

- Family: Dermochelyidae

- Genus: Dermochelys

- Species: D. coriacea