Eptesicus fuscus

Type: mammal

Status: special concern

Species Guide

Big brown bat

Eptesicus fuscus

Species Type: mammal

Conservation Status: special concern

IDENTIFICATION

Big brown bats are a relatively large, hardy bat whose size ranges from about 4.3-5 inches long, with the tail comprising almost 40% of its total body length. Big browns weigh about 23 grams, on average, with females growing slightly larger than males. The wingspan is approximately 13 inches. Fur color varies; their backs can range from light tan to dark brown, while their underbellies are generally light tan to olive in color. Their furless faces, ears, and wing membranes are black.

Distribution & Habitat

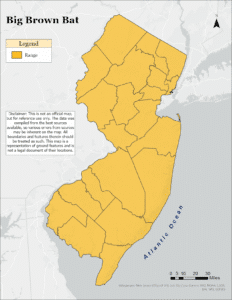

Big brown bats occupy a wide geographic range from northern Canada to the southern tip of Mexico, through Central America, and into Northern South America. They are extremely versatile in their habitat choices and will hunt for insects over water, open forests, cliff sides, and even deserts. Day roosts are typically found in deciduous forests, with maternity colonies forming beneath loose bark or in tree crevices. Colonies may also use tree-lined meadows or water bodies.

With a species name meaning “house-flyer,” big brown bats are commonly found roosting in man-made structures like house attics, eaves, barns, silos, and church steeples, in urban areas as well as rural ones. Female big brown bats form large maternity colonies from spring through summer – sometimes numbering hundreds of bats. Maternity roosts are chosen specifically for their warmth and safety, since this is where the mothers give birth and raise their young. Male bats are mainly solitary and are far more flexible about where they roost. The bats will often stop to rest and digest their evening meals in trees before returning to their day roosts by dawn.

Big brown bats hibernate underground in caves and mines, or in buildings where temperatures seldom drop below freezing. The bats are loyal to their roosts and will generally return year after year.

Diet

Big browns, like other insect-eating bats, are ecologically and economically important for their role in keeping pest populations in check. In addition to mosquitoes, they eat various types of moths and leafhoppers, including the destructive corn root worm moth. They also use their strong jaws to break through the tough shells of stink bugs, cucumber beetles, scarab beetles, and others. Studies have found that big brown bats can consume between 1.4 and 2.7 grams of insects per hour. They eat approximately half their own body weight in insects each night from spring through fall; double that for nursing females.

Life Cycle

In spring and summer, female big browns form maternity colonies that can comprise several hundred bats. These colonies often use trees or man-made structures that get a lot of sun exposure, which is important for gestation and keeping pups warm. Females give birth to one or two pups in late May or June and nurse them for approximately 4 weeks, by which time the young are nearly full-grown and strong enough to begin flying and foraging for themselves. Males roost alone or in small bachelor groups during the summer. Winters are spent in hibernation either in caves or mines or inside man-made structures.

Big brown bats can live up to 19 years in the wild, with males generally living longer than females. Many bats perish during hibernation from lack of sufficient fat stores. Natural predators of the big brown bat include climbing animals like snakes and raccoons, which hunt bats in their maternity roosts. Owls and hawks are also known to prey on bats as they exit their roosts at night for feeding.

Current Threats, Status, and Conservation

The big brown bat is among the most common and widespread bats of North America and is classified as a “least concern” species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN). Big brown bats are among the cave-hibernating species to be affected by White-nose Syndrome (caused by the fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans), though they have fared much better against this disease than the smaller-bodied Myotis and Perimyotis species. In fact, summer roost counts across New Jersey have shown an increase in big brown bat numbers since White-nose Syndrome first struck in 2009.

Conservation efforts include post-White-nose Syndrome monitoring, restricting recreational cave access to slow the Syndrome’s spread, educating homeowners and wildlife control companies about the proper handling of bat problems in the home, and improving the public’s awareness and sympathy toward bats.

In 2013, the New Jersey Endangered and Nongame Advisory Committee recommended a Special Concern status for this species within the state and the status update was officially adopted in January 2025.

Learn about the work being done to research and protect NJ’s bats at our Bat Project webpage.

References

Text written by Heather Kopsco and MacKenzie Hall in 2014.

Scientific Classification

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Mammalia

- Order: Chiroptera

- Family: Vespertilionidae

- Genus: Eptesicus

- Species: E. fuscus