Gelochelidon nilotica

Type: bird

Status: special concern

Species Guide

Gull-billed tern

Gelochelidon nilotica

Species Type: bird

Conservation Status: special concern

IDENTIFICATION

Gull-billed terns are medium-sized terns (about 15 inches in length) with a short black bill; black legs; and a black cap and nape (back of the neck). It has white underparts and a pale gray upper body, wings and a short slightly forked tail. In the winter, they will look similar, but will have a whitish head and a dark ear patch. Juveniles resemble non-breeding adults, but the outer wing will be darker and the base of the bill is paler.

The most common call of a gull-billed tern is a 2-noted, slightly upslurred kay-wek (ka-wek, kee-reek, or chu-veck), given singly or in series. Gull-billed terns produce other sounds such as alarms calls when predators approach (Aah or ack) and chips (shortened versions of Aah or ack) if disturbed at the nest.

Distribution & Habitat

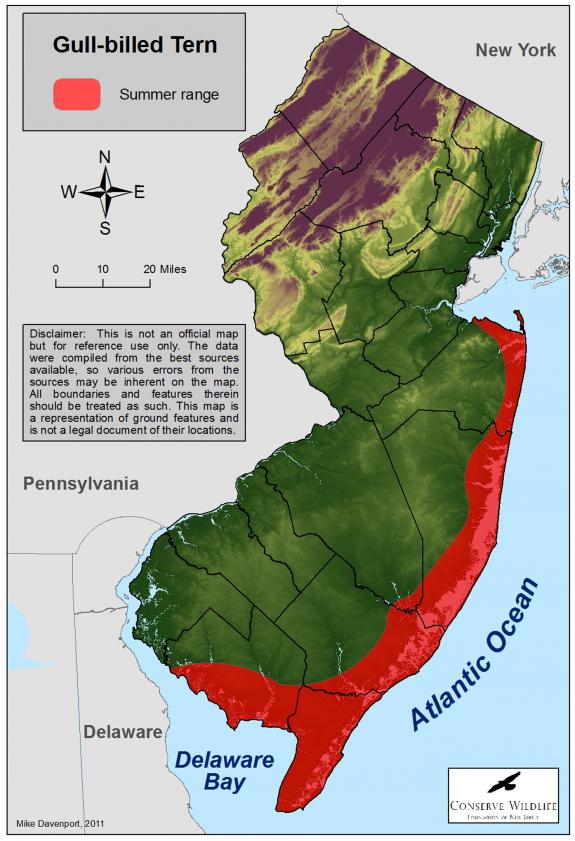

Gull-billed terns can be found breeding in Europe, Asia, northwest Africa, Australia, and the Americas. Within the U.S., gull-billed terns nest only in coastal colonies along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, generally from southern New Jersey to Florida and then along the Gulf Coast to Texas. Gull-billed terns are also found in southern California, but restricted to a single coastal site and one in the interior of the state. Eastern North American birds winter along the Atlantic Coast as far north as North Carolina, but generally in southwest Florida, along the Gulf Coast, and Mexico.

Gull-billed terns often nest singly or in small to medium-sized groups (5-50 pairs) at the edge of other bird colonies, such as the common tern (Sterna hirundo), least tern (Sternula antillarum), and black skimmer (Rynchops niger) and in California, Caspian (Hydroprogne caspia) and Forster’s terns (Sterna forsteri). Along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, nesting habitat includes barrier island beaches or mainland beach strands, saltmarsh islands, and especially near ocean-inlets. If nesting occurs in New Jersey, it may be more common in the saltmarshes as opposed to coastal beaches. Wintering habitat includes estuaries, saltmarshes, lagoons and plowed fields, and sometimes along lakes, rivers, and freshwater marshes.

Diet

Gull-billed terns feed on insects, small crabs, and other prey caught from the air or picked up off the ground or the surface of water. Gull-billed terns do not rely on fish to eat and rarely dive after fish as other terns do, but they will steal fish from other small terns when sharing colonies with them. Gull-billed will also eat small chicks of shorebirds and least terns.

Life Cycle

Gull-billed terns arrive in New Jersey early to mid-May. They may form pairs before they arrive on their breeding grounds as pairs are regularly seen migrating in the spring along the Atlantic Coast.

Both the male and the female will participate in scraping to make a nest, but no information is available on which sex initiates scraping. They may make several scrapes, but they only use one for their nest. Sand is scraped to form a hollow bowl-like depression in the sand and then lined with bits of shells or other materials such as twigs, grasses, or dead sedge stems if nesting in habitats with more vegetation or in marshes. Terns will begin laying an average of 3 eggs around mid-May to early June. Eggs are oval and may be yellowish beige in color and marked with brown spots. The eggs are incubated for approximately 22-23 days by both the male and female.

The hatched young are covered in downy feathers. Young chicks less than 5 days old may leave the nest but remain close to be fed by the parents. Chicks are ready to fly at about 30 days old (range 28–35 days). Even if fledged, they will remain with their parents to be fed for at least another 4 weeks and may also depend on their parents at the beginning of migration. Families may even remain together at least 2–3 months after fledging.

Current Threats, Status, and Conservation

Historically, gull-billed tern populations were hurt by egg collectors and hunters for the use of their feathers. Protection under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 and changing fashion trends may have enabled numbers to rebound. However, abundance along the Atlantic Coast in North America during the 1800’s and 1900’s remains uncertain. Gull-billed terns were rare in New Jersey historically and were still uncommon in the 1980’s and 1990’s.

The gull-billed tern is not abundant in any parts of its North American range and is now included in the USFWS list of Birds of Conservation Concern (2002, 2008), which identifies species that, without additional conservation actions, are likely to become candidates for listing under the Endangered Species Act of 1973.

During New Jersey surveys (a one-time aerial survey on a given year), individual gull-billed tern counts ranged from 0 to 140 birds between 1985 and 2011 (data provided by the NJ Endangered and Nongame Species Program, 2011). Note: The counts only capture a snapshot of the population in the Atlantic coastal marshes in a given year and only include birds associated with a colony. Surveys are not conducted each year and are not considered to be statewide, comprehensive efforts, but rather serve as an index of the population over time.

Development and elevated recreational use of coastal habitats are major factors contributing to the decline of this species. The gull-billed tern seems less tolerant to disturbance than other terns. Flooding and predation also account for nest loss. In New Jersey, in coastal beach areas with intense human activities, gull-billed terns have shifted to nesting on marshes and dredged-material sites, where disturbance is less intense. Effective management may include fencing and signs, predator control, and providing areas of suitable nesting habitat.

Learn about the work being done to research and protect NJ’s beach nesting birds at our Beach Nesting Birds Project webpage.

References

- Molina, K. C., J. F. Parnell and R. M. Erwin. 2009. Gull-billed Tern (Gelochelidon nilotica), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online.

- Stokes, D.W. and L.Q. Stokes. 1996. Stokes Field Guide to Birds Eastern Region. 1st ed. NewYork: Little, Brown, and Company. Print.

Edited in 2011 by Stephanie Egger.

Scientific Classification

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Aves

- Order: Charadriiformes

- Family: Laridae

- Genus: Gelochelidon

- Species: G. nilotica