Lanius ludovicianus migrans

Type: bird

Status: endangered

Species Guide

Loggerhead shrike

Lanius ludovicianus migrans

Species Type: bird

Conservation Status: endangered

Identification

The loggerhead shrike is about the size of a robin. They have a large gray head. The bill is hooked and black. They have a black facial mask that extends across the forehead and behind the eyes. The plumage on the back is gray. The wings are black with a white patch at the base of the outer wing or flight feathers. The tail is black and the underparts are pale gray.

The loggerhead shrike lacks is a predator, but it lacks sharp talons like those found on hawks. Instead it has the legs and feet typical of passerines or songbirds. The sexes are similar in plumage. Male shrikes are larger than females. Juvenile shrikes are duller in color than adults. They have brown flight feathers and are faintly marked with buff barring on their bodies. Loggerhead shrikes often perch in a horizontal posture on fence posts or wires. They fly in a low, undulating (up and down) flight with quick wingbeats.

The name shrike comes from the word “shriek.” It refers to the vocalizations of these birds. Shrikes emit both harsh, screeching calls as well as a musical song. The song of the loggerhead shrike consists of a series of two-noted liquid trills and guttural notes repeated over short intervals.

Distribution & Habitat

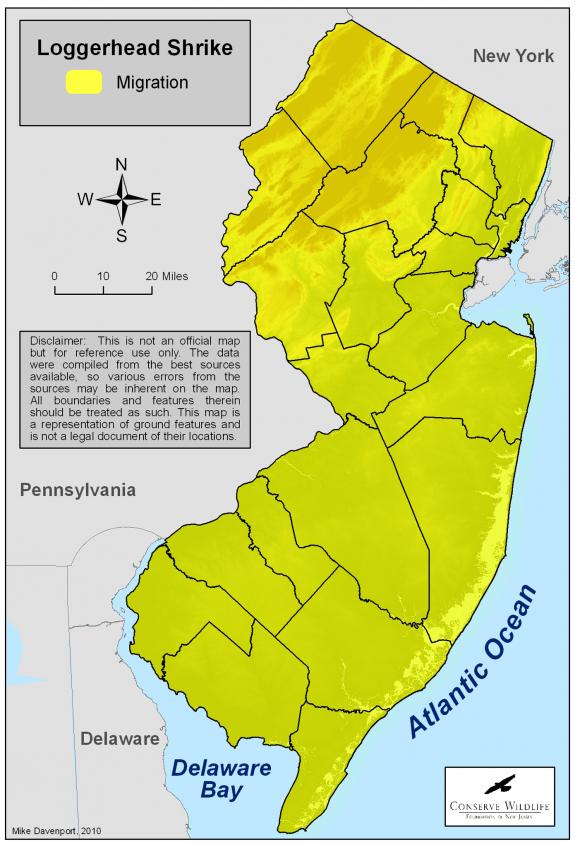

The loggerhead shrike is widely distributed throughout North America. They occur from southern Canada throughout the United States south to Mexico.

Loggerhead shrikes inhabit a variety of open areas. Habitat types include short-grass pastures, weedy fields, grasslands, agricultural areas, swampy thickets, orchards, and right-of-way corridors. Shrikes occupy sites that contain hedgerows, scattered trees or shrubs, and utility wires or fence posts. They use these features as perches. Nests are often located in trees or shrubs bearing thorns. Some preferred species include, hawthorns (Crataegus spp.), osage orange (Maclura pomifera), and multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora). Red cedar (Juniperus virginiana) may also be used for nesting. Similar habitats are occupied year-round.

Diet

Loggerhead shrikes are opportunistic predators. They consume insects, small mammals, songbirds, snakes, frogs, lizards, and even small turtles. In summer, shrikes eat a large number of insects, small mammals, and songbirds. In winter, small mammals and songbirds comprise most of their diet.

Shrikes hunt from perches like fence posts and telephone wires. They perch high above their habitat to look for prey. When prey is sighted shrikes pounce on and kill it instantly.

Since shrikes lack talons they utilize thorns and other sharp objects to impale their prey. They use these sharp objects to anchor and immobilize their prey when they feed on them. Impaling prey allows shrikes to cache or store food and catch prey that would otherwise be to large to handle.

Life Cycle

Loggerhead shrikes occupy large territories that are vigorously defended. During courtship males perform aerial displays and deliver food to potential mates. Male and female shrikes gather nesting material, but the female always builds the nest. The female builds the nest in a thorny shrub or tree that provides cover. Nests are constructed of twigs, weeds, bark, and are lined with grasses, lichens, moss, string, hair, or feathers.

In mid-April females lay 5 to 6 brown speckled-white eggs. She starts to incubate after the first egg is laid. She incubates the eggs for 16 to 20 days. The male provides all the food during this period. The young hatch asynchronously, or in the order that they are laid. This adaptation results in young that are staggered in ages. During years when prey is limited only the oldest and strongest young may survive. When the young hatch the females broods them closely. They are born blind and naked, or altricial, and are completely dependent on the adults. At 17 to 21 days old the young leave the nest but are still unable to fly. By 30 days the young fledge or fly for the first time. After fledging the young practice catching prey and learn skills that they will use for the rest of their life. They are fed by the adults for an additional 3 to 4 weeks after they fledge. Juvenile shrikes breed the following spring.

Current Threats, Status, and Conservation

The clearing of eastern forests for agriculture during the 19th century created habitat for several species of grassland and edge birds, including the loggerhead shrike. The abundance of small farms, pastures, and hedgerows in the northeastern United States enabled this shrike to expand its breeding range. When mechanized agriculture began to expand large monocultures of agriculture operations, high quality shrike habitat was diminished. Many open areas were also lost to development or matured into forests. Consequently, the breeding range and the number of loggerhead shrikes in the Northeast began to decline by the early 1960’s. The heavy use of pesticides, particularly DDT, accumulated in the prey of shrikes and resulted in eggshell thinning, reproductive failure, and contamination of adults and young.

Severe habitat loss and pesticide contamination was disastrous to nesting loggerhead shrikes in the northeastern United States. Since the 1970s, loggerhead shrike numbers have plummeted and breeding populations have been extirpated from much of this region. Declines were observed in breeding bird population from the late 1960s into the late 1990’s. Declines were also observed on the wintering areas of shrikes from the late 1950’s to late 1980’s. This shrike was listed as a Nongame Migratory Bird of Management Concern by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1982 and 1987.

Due to severe population declines and habitat loss, the loggerhead shrike was listed as an endangered species in New Jersey in 1987. Rare throughout much of the Northeast, the loggerhead shrike is also listed as endangered in New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia. Habitat loss is still considered to be the main threats to loggerhead shrikes in New Jersey today.

References

Beans, B.E. and Niles, L. 2003. Endangered and Threatened Wildlife of New Jersey.

Edited and updated in 2010 by Ben Wurst.

Scientific Classification

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Aves

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Laniidae

- Genus: Lanius

- Species: L. ludovicianus