Lasionycteris noctivagans

Type: mammal

Status: special concern

Species Guide

Silver-haired bat

Lasionycteris noctivagans

Species Type: mammal

Conservation Status: special concern

IDENTIFICATION

The silver-haired bat has long, silvery-tipped black fur. This “frosted” effect is similar in the hoary bat, but the hoary’s fur is distinctly yellowish at the base and across its face. The silver-haired bat is also smaller. A mid-sized bat, the silver-haired typically weighs 8 to 11 grams and is 3.5 to 4.5 inches long with a 12-inch wingspan. It has small, rounded, hairless black ears. Its dorsal tail membrane is covered in fur for insulation.

Silver-haired bats are slow but agile in flight. They are usually seen alone or in small groups.

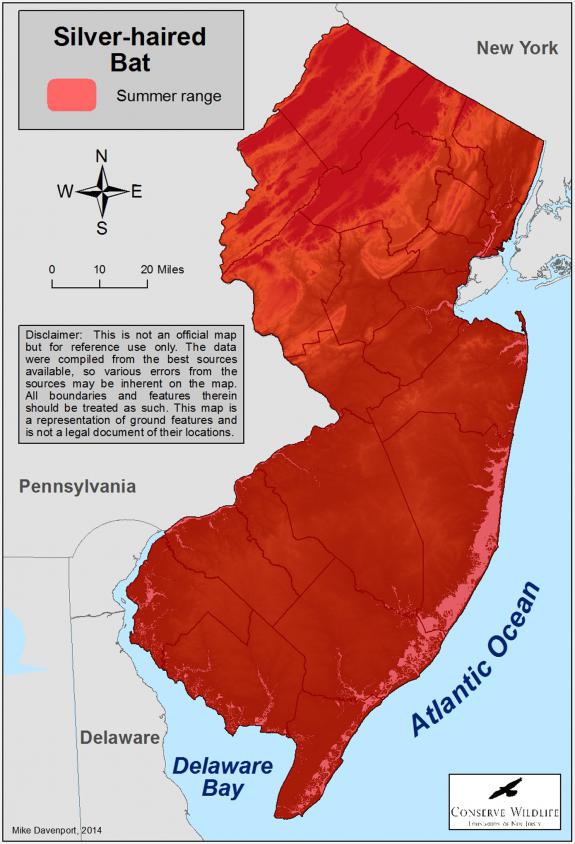

Distribution & Habitat

Silver-haired bats are found in deciduous and coniferous forests throughout the United States (except for Florida), across southern Canada, and in northern Mexico. They roost by day beneath the loose bark of trees or in cavities created by other animals. Roosts are usually near a water source. Silver-haired bats rarely inhabit man-made structures.

This species is considered migratory; silver-haired bats typically fly to the southern parts of their range for winter and return north in early spring. Some individuals spend the winters hibernating in tree hollows, beneath the leaf litter in forests, near the front of caves and mines, or in other insulated microhabitats.

Diet

Like all bats in our region, silver-haired bats feed on night-flying insects. They favor a diet of moths, flies, and beetles but are opportunistic as well. Silver-haired bats often begin feeding before nightfall, perhaps to get a jumpstart before most other bats are active. They often forage low over water and in forest clearings. They are also known to feed on insect larvae in and on tree bark, and also to glean insects from the forest floor.

Silver-haired bats use echolocation to navigate and find their prey while flying. They emit rapid high-frequency call pulses, and the returning echoes reveal the size, shape, distance, and trajectory of insects, enabling the bats to hone in on their prey and ultimately snatch them from the air.

Life Cycle

Silver-haired bats are solitary during the summer. They mate in August and September while gathering for migration and will make the journey in groups. Females store sperm through the winter hibernation period; ovulation and fertilization occur in the spring. This species gives birth to two pups, typically, in late June or early July. The mother will face right-side up during the birthing process, hanging by her thumb nails, and catches her young with her tail membrane (called the uropatagium). The pups are nursed for 3 to 5 weeks, by which time they are able to fly and feed on their own.

Most silver-haired bats migrate south for the winter, setting out in August or September and returning north in early spring. Some, however, remain north and hibernate during winter.

Silver-haired bats can live up to 12 years. Natural predators of this species include great-horned owls, striped skunks, and other opportunistic animals.

Current Threats, Status, and Conservation

Silver-haired bats are susceptible to the same gradual habitat loss as most forest-dwelling wildlife, and to forestry practices that remove dead and dying trees which the bats roost in. Since silver-haired bats are primarily migratory, they have not suffered the devastating losses to White-nose Syndrome (WNS) that cave-hibernating species have, though one individual of this species to-date was confirmed WNS-positive in a hibernaculum in Delaware.

Silver-haired bats and other migratory species are, however, taking massive hits from wind farms along their migration routes. Recent studies estimate that around 500,000 bats (mainly red bats, hoary bats, and silver-haired bats) may now be killed annually by wind turbines in the U.S. Researchers believe that bats are drawn to the turbines as places to perch, hunt for insects, or engage with mates, or simply for curiosity’s sake. Bats are either struck by the fast-moving blades or killed by barotrauma – the damage to air-containing organs caused by rapid pressure change. A working group called the Bats and Wind Energy Cooperative (BWEC) was formed in 2003 to tackle this emerging issue. Solutions include seasonal adjustments to turbine cut-in speeds (wind speed at which the blades start spinning), acoustic and/or light deterrents, and avoiding turbine development in high-risk locations.

In 2013, the New Jersey Endangered and Nongame Advisory Committee recommended a Special Concern status for this species and the status update was officially adopted in January 2025.

Learn about the work being done to research and protect NJ’s bats at our Bat Project webpage.

References

- State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry

- University of Michigan Museum of Zoology

Text written by Heather Kopsco and MacKenzie Hall in 2014.

Scientific Classification

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Mammalia

- Order: Chiroptera

- Family: Vespertilionidae

- Genus: Lasionycteris

- Species: L. noctivagans