Myotis septentrionalis

Type: mammal

Status: endangered

Species Guide

Northern long-eared bat

Myotis septentrionalis

Species Type: mammal

Conservation Status: endangered

Federal Status: endangered

State Status: endangered

IDENTIFICATION

The northern long-eared bat (a.k.a. northern myotis) is one of four New Jersey bat species belonging to the Myotis genus. It is similar in size and appearance to the little brown bat (M. lucifugus) and Indiana bat (M. sodalis), with an average weight of 6 to 9 grams, a body length of around 3 inches, and a 9 to 10 inch wingspan.

The northern long-eared bat’s rounded ears are longer than those of its relatives, though not dramatically; they are 17 to 19 mm (~0.7 inch) long and extend past the bat’s snout when folded forward. The northern’s tail and wings are also generally longer than those of other Myotis species. Its fur is brown with a dull yellow hue and a darker spotting pattern on its shoulders. Females of this species are usually larger than males.

Distribution & Habitat

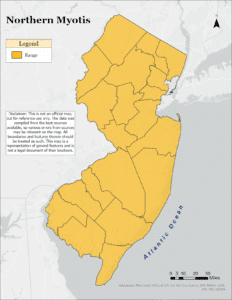

The northern myotis can be found from the boreal forests of northwestern North America (Alberta, Canada, and surrounding territories), east to Newfoundland, and south through most of eastern North America, including the central and south-central U.S. states.

These bats inhabit dense forests, roosting by day beneath the loose bark of trees or in tree crevices. They are more solitary than other myotids and often roost alone, but will form maternity colonies consisting of mothers and their young. Little is currently known about their feeding habits, but northern long-eared bats have been seen foraging for insects among trees and above ridge lines, along forest edges, and occasionally over water bodies.

They hibernate in winter, preferring the cool, stable temperatures provided by caves and abandoned mines. Though rarely, the northern myotis may use buildings as both summer roosts and winter hibernation sites.

Diet

Northern long-eared bats are insectivores. They hunt and feed upon a variety of small flying insects, including caddisflies, moths, beetles, and leaf-hoppers. Like other bats, they forage in flight in forest clearings, edge habitats, and over water where insects are abundant. These bats also sometimes glean prey from tree branches, rocks, and other surfaces.

Like other insect-eating bats, northern myotis use echolocation to navigate and find their prey. These bats emit high-frequency calls – around 20 pulses per second – while searching. The echoes reveal the size, shape, distance, and trajectory of insects, enabling bats to follow their movements and ultimately snatch their prey from the air. As they hone in, the bats increase their calls to up to 200 pulses per second in what is referred to as the “feeding buzz.” A single northern myotis consumes more than half its own body weight in insects each night from spring through fall; it may catch 1,000 or more mosquito-sized insects an hour during peak foraging. Nursing females are even more voracious, consuming up to 110% of their own body weight in insects each night.

Life Cycle

Like most bats, the northern myotis engages in mating in the fall, right before hibernation. Females store sperm over the winter and ovulate in the spring, delaying pregnancy until food resources are available again. They arrive at their maternity roosts around mid-May, and pups are born in late May or June following a 50-60 day gestation period. Females give birth to just one pup per year. Males live separately from females and are not involved in pup rearing. Pups nurse for approximately four weeks until they are nearly full-grown and strong enough to begin flying and foraging on their own. Sexual maturity is reached at approximately one year. Northern long-eared bats live almost 20 years in the wild.

Current Threats, Status, and Conservation

Currently, the northern myotis is classified as a “least concern” species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN). However, due to the bats’ dependence on dense forest, timber cutting can threaten maternity colonies and other roost sites.

In winter, their underground hibernation sites are prime environments for Pseudogymnoascus destructans, the fungus responsible for causing White-nose Syndrome (WNS) in several North American bat species since 2006. The disease causes wing deterioration, water loss, and arousals that cost bats their critical energy reserves when food is not available. The northern myotis has been one of the hardest hit species, suffering a staggering 98% reduction in numbers in WNS-affected areas. As a result, the US Fish and Wildlife Service proposes to list the northern myotis as Endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

On November 29, 2022 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) published a final rule to reclassify the northern long-eared bat (NLEB) as endangered under the Endangered Species Act. This species is also listed as endangered within the state of New Jersey.

Learn about the work being done to research and protect NJ’s bats at our Bat Project webpage.

References

- Bat Conservation International

- Center for Biological Diversity

- University of Michigan Museum of Zoology

Text written by Heather Kopsco and MacKenzie Hall in 2014. Updated by Mike Davenport in 2015.

Scientific Classification

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Mammalia

- Order: Chiroptera

- Family: Vespertilionidae

- Genus: Myotis

- Species: M. septentrionalis