Myotis sodalis

Type: mammal

Status: endangered

Species Guide

Indiana bat

Myotis sodalis

Species Type: mammal

Conservation Status: endangered

Federal Status: endangered

Identification

The Indiana bat is about 3.5 inches long with a 10 inch wingspan. It very closely resembles the common little brown bat and the northern long-eared bat. A few small details distinguish the Indiana bat: it has grayish lackluster fur that’s lighter on the belly, a pink nose, and shorter, sparser toe hairs than the other bats. The Indiana bat also has a strongly keeled (or ridged) calcar, which is the piece of cartilage that connects a bat’s wing membrane from the foot to the tail.

Distribution & Habitat

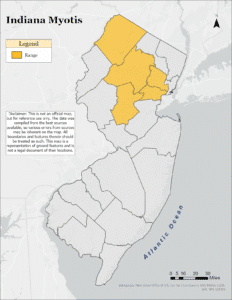

Indiana bats are found over most of the eastern half of the United Sates, from Michigan, New York, and Connecticut in the north, and southward to Florida and Alabama. Their range stretches westward to Iowa, Missiouri, Arkansas, and Oklahoma. The Indiana bat is among the six NJ bat species that are active throughout the late spring, summer, and early fall but go into dormancy during the cold winter months, hibernating in caves and abandoned mines (three other NJ bat species migrate south for the winter).

The Indiana bat is highly selective of hibernation sites, called hibernacula. It tends to prefer medium-sized caves with large, shallow passageways. Ideal conditions insides caves include an average temperature of 37 to 43 degrees Fahrenheit and a relative humidity of 87%. Indiana bats can hibernate together in clusters of more than 400 bats per square foot. They often hibernate with other species. At the Hibernia Mine in Morris County, New Jersey, Indiana bats hibernate primarily with little brown bats, as well as lower numbers of northern long-eared, tri-colored (pipistrelle), big brown, and eastern small-footed bats.

During the summer, female Indiana bats occupy maternity roosts of up to 100 or more females. They tend to roost under the bark of dead and dying trees but have also been found living under the loose bark of living trees such as the shagbark hickory. Roost trees are generally in sunny locations near water, where insects are plentiful and mother bats can replenish the liquids needed for nursing. Males tend to roost alone or in small groups, usually near female roosts. However, some adult males may choose to occupy caves during the summer as well. Roost sites tend to be located far from roads, usually at least 3,000 feet.

Diet

All of NJ’s bats are insectivores and can consume more than half their body weight in insects every night. Indiana bats eat a variety of flying insects, including moths, beetles, termites, flies, and mosquitoes. Male Indiana bats may travel up to 2.5 miles a night while foraging. A drop in insect-eating bats increases the need for chemical pesticides, costing landowners and farmers more while harming fragile ecosystems.

Life Cycle

Caves and mines are important locations for mating and hibernation. From September to mid-October, Indiana bats form “swarms” outside their hibernacula where they bulk up on food for their winter slumber and engage in mating. The bats will not eat again until spring, and hibernation allows them to conserve precious energy. Indiana bats have delayed fertilization, meaning that females do not become pregnant until spring emergence. Gestation lasts about 50 to 55 days. Females generally give birth to one pup (sometimes two) after reaching their maternity colonies. Females will nurse their young for about a month until they are able to fly, and thus feed, on their own. Migration back to their hibernacula – a journey that can be over 300 miles – begins in August and continues into early September. Indiana bats may live up to 20 years, but 8-10 years is typical.

Current Threats, Status, and Conservation

New Jersey biologists have studied bats, including the Indiana, for several decades. Winter surveys inside known hibernacula allow bat populations to be tracked over time. Exploration of many other caves and abandoned mines may lead to more hibernacula being protected. Bat surveys during spring emergence provide information about normal post-hibernation health and enable bats to be banded for future observation. Radio-telemetry and mist netting projects by the US Fish and Wildlife Service continue to answer questions about the Indiana bat’s roost preferences, distribution, and behavior.

Since 2003, the Conserve Wildlife Foundation of NJ (CWF) has managed the Summer Bat Count, an annual volunteer project to monitor bat populations at known roost sites like attics, barns, bat houses, and churches. This project helps us further understand the bats’ roost selection, distribution across NJ, and trends.

In January of 2009, NJ biologists discovered the presence of White-nose Syndrome (WNS) at three of the largest bat hibernacula in the state. WNS is named for the white fungus that appears on the muzzles and other membranes of affected bats, which as a result of the condition often die of starvation and dehydration over winter. Mortality rates are nearly 100% at many sites. As of April 2009, just three winters since its discovery in New York, WNS had spread to nine northeast states and killed an estimated one million bats.

“Mortality rates (from the effects of white-nose syndrome) are nearly 100% at many sites.”

New Jersey is participating in several research projects that are looking into the causes of WNS, its means of spreading, and possible treatments or solutions. Spring emergence surveys, summer bat counts, bat banding, fur and tissue sampling, and maternity colony monitoring are a few ongoing efforts. CWF is also working with forest landowners in north Jersey to create natural roosts for tree bats like the Indiana bat. Since tree bats prefer to roost under loose or dead bark in sunny locations, these projects include girdling (killing) select trees, clearing other trees around them to increase sunlight, and attaching loose-bark mimicking materials to provide bats with extra, longer-lasting shelter. Hibernia Mine, wintering home to some of NJ’s Indiana bats, was gated in 1994 to protect them.

Learn about the work being done to research and protect NJ’s bats at our Bat Project webpage.

Scientific Classification

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Mammalia

- Order: Chiroptera

- Family: Vespertilionidae

- Genus: Myotis

- Species: M. sodalis