Pandion haliaetus carolinensis

Type: bird

Status: stable

Ben Wurst

Species Guide

Osprey

Pandion haliaetus carolinensis

Species Type: bird

Conservation Status: stable

The osprey, formally known as the “fish hawk,” is one of New Jersey’s largest raptors. They are well known and highly visible in coastal areas. The bird is distinguished by its dark underwing patches and the crook at the wrist joint of the long, narrow wing, which is always bent. Adult birds have dark brown body feathers on its back and wings contrasting with their white crown, neck and undersides. Broad dark stripes appear on either side of the head, running through the eye. The eye color changes from red to orange to yellow as they mature. The tail is light with fine dark bands and a broad terminal bar edged in white. Both sexes have similar plumage. The female is slightly larger than the male and exhibits a more prominent “necklace” of dark feathers on their chest. Females also have more brown flecking on their underwing coverts, while males do not. Osprey’s average wingspan is 63 inches and weighs about 3 pounds.

Distribution & Habitat

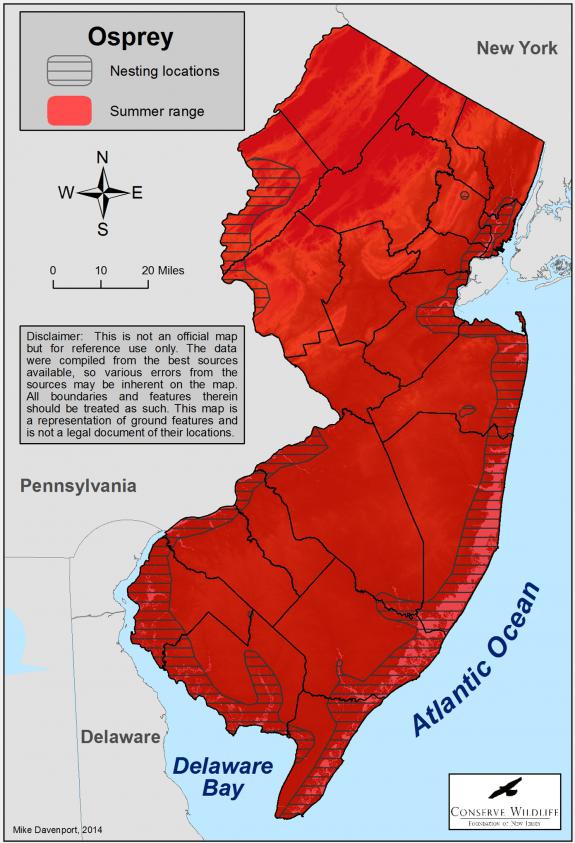

The osprey is one of the most widely distributed birds in the world, yet its preference for fish requires that it live close to the water. In North America, its range extends from Alaska to Baja California, and along the Atlantic coast from Labrador to Florida. In New Jersey, ospreys nest along the Atlantic Coast from Sandy Hook to Cape May, and along the Delaware Bay and River in Cumberland, Salem, and Gloucester counties. As a result of reintroduction efforts on northern New Jersey lakes, ospreys also nest along the upper Delaware River and their range expanded into the Meadowlands, which clearly shows the improvement in the health of the local environment. Ospreys prefer to build their large stick nests close to water on both living and dead trees, channel markers, duck blinds, utility poles, communication towers. More recently, man-made or artificial nest platforms placed on the salt-marsh have replaced trees and are largely responsible for the recovery of ospreys in the state.

The osprey is one of the most widely distributed birds in the world, yet its preference for fish requires that it live close to the water. In North America, its range extends from Alaska to Baja California, and along the Atlantic coast from Labrador to Florida. In New Jersey, ospreys nest along the Atlantic Coast from Sandy Hook to Cape May, and along the Delaware Bay and River in Cumberland, Salem, and Gloucester counties. As a result of reintroduction efforts on northern New Jersey lakes, ospreys also nest along the upper Delaware River and their range expanded into the Meadowlands, which clearly shows the improvement in the health of the local environment. Ospreys prefer to build their large stick nests close to water on both living and dead trees, channel markers, duck blinds, utility poles, communication towers. More recently, man-made or artificial nest platforms placed on the salt-marsh have replaced trees and are largely responsible for the recovery of ospreys in the state.

Ospreys winter in Florida, the Gulf Coast states, and as far down as Central and northern South America. New Jersey ospreys fitted with satellite transmitters have been tracked to Venezuela and Colombia to Brazil’s Amazon River Basin. The majority of New Jersey birds winter in northern South America.

Diet

Special adaptations make the osprey exceptional at fishing. Most notable is their amazing eyesight, with very large eyes, ability to perceive UV light and more photoreceptors which enhances their visual acuity. Another special adaptation is the bird’s outermost toe, which can reverse to oppose the the other two (most birds grip with three toes in front, and one in back), this attribute is referred to as zygodactyl. It uses this grip to carry fish head first to reduce wind resistance. It has long legs, and its feet and toes are equipped with tiny spines, or spicules, that enable them to grasp slippery fish. The osprey will dive several feet into the water (up to 1 meter), feet first, after fish. An osprey’s diet consists almost entirely of fish.

Their diet differs throughout their range and the time of year. Ospreys are opportunistic predators. They hunt on the wing and can hover. They have four types of color receptors in the eye (humans only have three). This gives them the ability to perceive ultraviolet light, which makes some fish with iridescent markings, like flounder, easy prey. During early spring when ospreys return in late March the shad and herring migration is getting underway. They also forage more on inland lakes and ponds when freshwater fish become more active and trout are stocked in many waterbodies. Then striped bass begin to move inshore and in summer, flounder and Atlantic menhaden are plentiful and are often their main prey items.

Life Cycle

In New Jersey, ospreys arrive on breeding grounds in late March, usually to the same nests each year, meaning they have a high level of site fidelity. Older more experienced birds arrive first, especially males. Ospreys mate for life and are monogamous. Pairs begin courtship and nest building in early April. Males perform courtship displays that consist of a high undulating flight, called the “sky dance,” sometimes after a successful hunt where he holds a fish or nesting material and calls out with a high pitched whistle like sound. This strengthens their pair bond. Males do 100% of the foraging from courtship until the young fledge. Females do around 70% of the incubation duties. Eggs are laid in mid-April to early May, usually three buff colored, brown spotted eggs. Incubation lasts 32-43 days, and most young hatch in late May. The chicks hatch semi-altricial or are helpless and require close parental care. To successfully raise a full clutch of young the male must provide enough fish (sometimes up to 6 lbs. a day) to feed all the hungry mouths. After a successful hunt he almost always stops at a nearby perch and consumes the head of the fish. If he feeds near the nest with the female on the nest she will beg for food from him. Young birds fledge the nest at 7-8 weeks of age in mid-late July. Adults continue to feed young in the area of the nest for several weeks while young ospreys learn flying and hunting skills. In late August and early September, ospreys leave New Jersey for their wintering grounds. This is also a great time to visit the coast to watch ospreys, as their numbers are plentiful as young learn to soar on thermals and forage at the beach. Females typically depart first and males and young follow. Migration peaks in Cape May during the first week of October.

The successful production of young is highly dependent on several factors. Weather plays a huge role in the reproduction of ospreys. Since they rely on fish as their main prey item, high winds and wet weather can have a negative effect on the success of foraging attempts. In years with a wet and cool spring, productivity rates dropped as adults had trouble finding and catching prey. In years with a warm spring and summer, ospreys fair quite well. An adaptation to help control this seasonal changes in their diet is that ospreys exhibit is asyncronous hatching. This is where incubation begins when the first egg is laid (laying occurs in two day intervals), not when the full clutch is laid. This gives the oldest chick the best chance at surviving if food is not plentiful. It is better for a pair to produce one very strong chick than 2-3 meager young. Finally, their success is also highy dependant on the male’s ability to successfully find and catch prey. In general, older males are often more experienced and in turn, can produce more young then at nests with young adults.

Current Threats, Status, and Conservation

From the late 1800s to the early 1960s, New Jersey’s ospreys were in decline. At one point, there were more than 500 nests along the entire coast. By 1974, only around 50 nests remained. Development after World War II, especially along the coast, widespread food contamination by persistent pesticides (mostly DDT), and persecution caused the birds’ decline in New Jersey and throughout the eastern U.S. Consequently, the osprey was listed as “endangered” by New Jersey Fish & Wildlife in 1973.

From the late 1800s to the early 1960s, New Jersey’s ospreys were in decline. At one point, there were more than 500 nests along the entire coast. By 1974, only around 50 nests remained. Development after World War II, especially along the coast, widespread food contamination by persistent pesticides (mostly DDT), and persecution caused the birds’ decline in New Jersey and throughout the eastern U.S. Consequently, the osprey was listed as “endangered” by New Jersey Fish & Wildlife in 1973.

Efforts to recover the osprey population began in 1974. This is when biologists partnered with other state/federal agencies on an innovative program to “transplant” osprey eggs and young from nests on the Chesapeake Bay, where DDT was not used as heavily. In addition, built and installed nest structures in and along the coastal marshes, to replace trees that had been lost to development.

Management efforts were successful in restoring osprey nesting in the state. In 1984 there were 108 nests and sustainable production, leading to their status being upgraded to “threatened” in 1985. By 1990, osprey nests numbered 170, and by 1993 there were 200 nests, a four-fold increase since 1974. Today, there are over 800 nesting pairs.

One of the most important management techniques for New Jersey ospreys is providing adequate nest structures along the coast. Over 400 nest platforms have been installed and over 75% of the current population nests on man-made platforms that are designed specifically for ospreys. These structures require maintenance and replacement as they age. Donors and volunteers have been valuable in providing funding and assistance with the installation of these nest structures.

Since 2007, over 100 nesting platforms have been installed on Barnegat Bay from Mantoloking south to Little Egg Harbor and west on the Mullica River. We continue to work towards a future where ospreys have plenty of natural sites to build nests, away from human disturbance.

Ospreys are proven indicators of environmental health. Feeding largely on fish, their health directly reflects the health of a food source shared by humans. A study performed by the Endangered and Nongame Species Program in the late 1990s showed that toxic and persistent pesticides have declined in ospreys in New Jersey. However, the effects of other contaminants like brominated flame retardants, including PTFEs, which are used in a large amount of consumer goods are little known. We currently collect addled eggs for future contaminant studies (if funding becomes available).

An emerging threat to ospreys is persistent plastic marine debris. Each year, ospreys become entangled or get suffocated by plastics, including monofilament/fishing line, balloon ribbon, rope/twine, plastic bags, and sheeting. According to data collected during summer nest surveys, around 40% of nests contain some form of plastic marine debris. Ospreys simply use plastic to decorate their nests, as it washes up in the same areas where they collect natural nesting material and it mimics many natural items.

A recent threat to ospreys has been severe weather and reduced availability of key prey, like Atlantic menhaden, which resulted in brood reduction and reduced productivity. In 2022 and 2023, nor’easters impacted the coast in May and June. This was during very important time periods, when osprey young are vulnerable and require multiple feedings per day. With high winds and rough waters, it is very difficult for coastal nesting ospreys to find and catch prey, especially in the ocean, where their main prey (menhaden) is found. After the severe weather subsided, many young ospreys perished from starvation in the following days and months as menhaden were not as plentiful.

In 2024, there were no nor’easters but early results from our nesting surveys showed that ospreys had another difficult year, with some pairs not laying any eggs or having reduced clutch sizes and delayed incubation. This was also observed in other areas, like the Chesapeake Bay. Wildlife toxicologists are currently investigating to try and determine the root cause of this, which may be from an unknown contaminant that they’re being exposed to. Finally, NJDEP proposed to change the status of ospreys from threatened (breeding population) to stable. The public comment period closed in early August and has yet to be decided on by regulators. This marks a huge success to the recovery of osprey but much effort is still needed to ensure that the population remains stable, mainly because the majority of the population relies on man-made nest platforms to reproduce successfully. CWF is committed to monitoring and managing ospreys using volunteers to help ensure they continue to thrive.

On January 6, 2025, NJDEP adopted a rule proposal changing the status of ospreys from threatened during their breeding season (April 1 – August 31) to stable. Since surpassing their historic population estimate of over 500 nesting pairs in 2013, this marks a monumental achievement for all of the hardworking and devoted biologists, volunteers, land managers, and members of the public, who have supported ospreys and ensured that our coastal environment is clean and healthy. “The removal of the bald eagle and osprey from New Jersey’s endangered species list is a remarkable accomplishment, made possible by the tireless efforts of our dedicated wildlife professionals,” said NJDEP Fish & Wildlife Assistant Commissioner Dave Golden. “The key to this success is a commitment to science, planning, and strong lines of communication with the public and stakeholders. However, there is still work to be done, and we remain committed to the professional management and conservation of all of our wildlife species here in the Garden State.”

At Conserve Wildlife Foundation of NJ, we remain devoted to monitoring ospreys in the future, as we have over the past two decades. We will do this by engaging with partnering organizations, volunteers and citizen scientists to monitor nests and maintain their nest platforms — which are crucial to their long term survival — as around 75% of the population relies on these structures to reproduce. Support from private foundations through grants and donations from the public are the lifeblood of our wildlife conservation efforts.

References

Text derived from the book, Endangered and Threatened Wildlife of New Jersey. 2003. Originally written by Sherry Liguori. Originally edited by B.E. Beans & L. Niles. Edited and updated in 2024 by Ben Wurst.

Scientific Classification

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Aves

- Order: Accipitriformes

- Family: Pandionidae

- Genus: Pandion

- Species: P. haliaetus carolinensis