Podilymbus podiceps

Type: bird

Status: endangered

Species Guide

Pied-billed grebe

Podilymbus podiceps

Species Type: bird

Conservation Status: endangered

Identification

The pied-billed grebe is a small, brown, duck-like diving bird. It has a stocky body, a thin neck, and a relatively large head. The undertail feathers (coverts) are white. The tail feathers are short and brown. This makes the grebe appear stubby and almost tail-less. The legs and lobed toes are gray. The bill is thick and stout. This enables the grebe to crack open hard shells of mollusks and crustaceans. In breeding plumage, the ivory-colored bill is encircled with a black ring and the throat is black. In non-breeding plumage, the throat is white and the bill is unmarked. The iris is dark reddish-brown. The eye is encircled by a thin white eye ring. Males are slightly larger than females, and the sexes are similar in appearance.

Young pied-billed grebes are downy and vividly marked with brown and white stripes on the head, neck, and body. They have rufous (reddish-brown) patches on the back of the head and behind the eye. The young have grayish-green legs and dark brown eyes. Juveniles resemble adults but may retain some brown and white streaking on the head and neck until October.

Pied-billed grebes spend nearly all their time on water. They quickly dive headfirst into the water. If threatened, a grebe may quickly dive or sink slowly into the water, emerging with only its head visible. The brown plumage of pied-billed grebes camouflages them among marsh vegetation.

They are well adapted for swimming underwater. Grebes are able to waterproof their feathers by preening them with secretions from an oil gland located at the base of the tail. Their eyes possess cone-dense retinas, an adaptation for locating prey underwater. They have relatively solid bones and compress their feathers to enable them to remain underwater longer. Their short, narrow wings aid in maneuverability when swimming. There legs are located father back on the body to help with propulsion underwater. They may be strong swimmers, but they are awkward on land. Grebes can only take off from water. They run along the water to gain speed then once enough lift is gained they can fly.

The call of the pied-billed grebe, which is given primarily during the breeding season, is a “ko-ko-cow-cow-cow-cowp-cowp.” Pied-billed grebes are extremely secretive during the breeding season and are much more likely to be heard than seen.

Distribution & Habitat

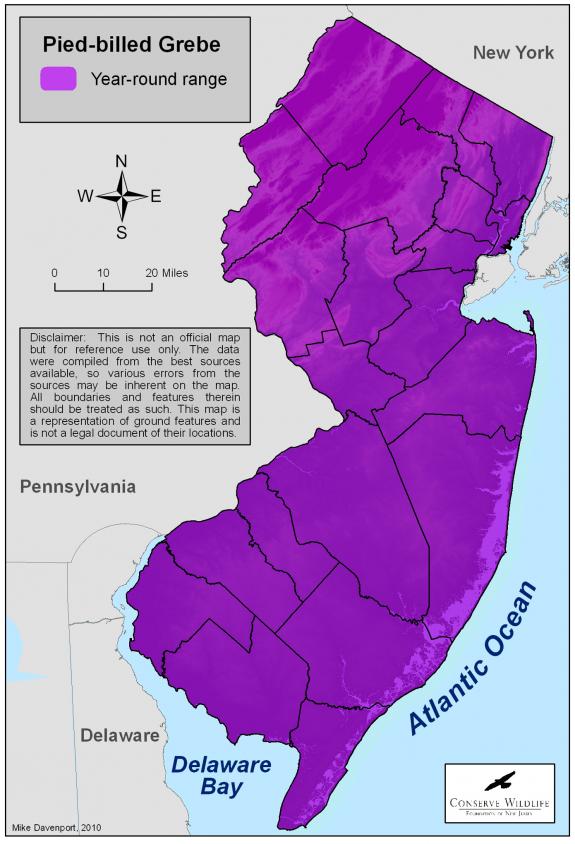

Pied-billed grebes breed throughout North America from southern British Columbia, Ontario, southwestern Quebec, and Alaska through the United States, Central America, and South America to Argentina and Chile. Grebes winter throughout the Americas, ranging from Massachusetts, Kansas, and Washington State south to Southern Argentina and Chile. Pied-billed grebes are rare breeders in New Jersey. There have been scattered nesting sites throughout wetlands in the state. They are a common migrant in the state. And many winter in here in New Jersey if open water remains.

Pied-billed grebes nest in freshwater marshes associated with ponds, bogs, lakes, reservoirs, or slow-moving rivers. Breeding sites typically contain fairly deep open water at depths of .8 to 6.6 ft. Sites are usually interspersed with submerged or floating aquatic vegetation and dense emergent vegetation. Marshes created by impoundments or through the busy actions of beavers (Castor canadensis) may serve as nest sites. Infrequently, pied-billed grebes nest in coastal estuaries that receive minimal tidal fluctuations.

Pied-billed grebes occupy a greater diversity of habitats during the nonbreeding season. Inland freshwater ponds, impoundments, lakes, rivers, brackish marshes, estuaries, inlets, and coastal bays may be inhabited. When freshwater freezes over, pied-billed grebes can be found in brackish marshes or tidal creeks.

Diet

Pied-billed grebes eat a variety of aquatic organisms. They eat fish, crustaceans, insects, mollusks, amphibians, seeds, and aquatic vegetation. Their diet fluctuates during the different seasons. In spring and summer they primarily eat invertebrates. During winter months they primarily eat fish. Oddly enough, grebes are known to eat their own feathers or they feed them to their own young. It is thought that this might aid in digestion.

Life Cycle

From late March to early April, grebes arrive on their breeding grounds. Grebes are highly territorial during the breeding season and require large areas of habitat. Sometimes several pairs may share suitable habitat in wetlands.

Both the male and female construct a floating nest. It is made of live and dead vegetation and is sealed with mud. It is located within vegetative cover and is anchored by live vegetation. The nest must be constantly maintained and repaired throughout the nesting season since it is made of organic materials. The nest generates heat when it rots away. The heat helps maintain a constant temperature when the adults are foraging.

As early as mid-April the female grebe lays a clutch of 6 to 8 white eggs. The eggs become stained by the mud in the nest and turn brown. Both adults incubate the eggs for 23 days. Soon after the hatching the young leave the nest. They can swim and dive underwater. They must be very careful of predators during this time. To help evade predation the young ride on the adults backs, even when they dive underwater. The young are fed insects at first then fish is added to their diet as the age.

Current Threats, Status, and Conservation

During the 1800’s, the pied-billed grebe was a fairly common breeding species within suitable habitat in New Jersey. Market hunters harvested grebes as food and for their feathers. Their feathers were used to make earmuffs and hats. Consequently, by the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, grebe populations were greatly reduced. By 1940, there were only 12 known nesting sites in northern New Jersey. The large amount of land preserved and managed for waterfowl from the 1940’s to the 1960’s facilitated an increase in grebe populations. Despite the protection of wildlife refuges, many marshes continued to be drained and filled. This resulted in a decline of nesting grebes in New Jersey since the 1970’s.

Due to population declines resulting from habitat loss, the pied-billed grebe was listed as a threatened breeding species in New Jersey in 1979. Even after it was listed, its habitat still continued to be destroyed and degraded. This resulted in further declines. In 1981, there were only two known breeding sites in the state. Due to its dire status in the state, the pied-billed grebe was reclassified as an endangered species in 1984. Concern for the pied-billed grebe is evident in other northeastern states, including New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Connecticut, where it is listed as endangered.

Habitat degradation and destruction resulting from the draining, dredging, filling, and pollution of wetlands are the greatest threats facing the pied-billed grebe population in New Jersey. Contamination from roadway runoff, pesticides, and herbicides also threaten pied-billed grebes and the aquatic organisms upon which they feed. Pied-billed grebes are also sensitive to human disturbance, particularly during incubation. Intruders can cause the adults to spend a prolonged duration away from the nest, leaving the eggs vulnerable to weather and predators. Boating activity near nest sites can disturb breeding grebes and destroy nests through increased wave action.

References

Beans, B. E. and Niles, L. 2003. Endangered and Threatened Wildlife of New Jersey.

Edited and updated in 2010 by Ben Wurst.

Scientific Classification

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Aves

- Order: Podicipediformes

- Family: Podicipedidae

- Genus: Podilymbus

- Species: P. podiceps