Rynchops niger

Type: bird

Status: endangered

Species Guide

Black skimmer

Rynchops niger

Species Type: bird

Conservation Status: endangered

The breeding adult black skimmer has brown-black upperparts, with a white forehead and underparts. The upperwing shows a white trailing edge from the secondaries to the inner primaries. The tail is white, with dark central feathers. The bill is black with a reddish-orange base. The legs and feet are also reddish-orange. Male black skimmers are slightly larger than females. Nonbreeding adult plumage is similar, but duller, than that of breeding adults. In winter, the bill and upperparts are somewhat paler. In addition, white feathers on the nape form a light collar around the neck.

Juvenile skimmers appear similar to adults, but have duller brown upperparts with light feather edges and streaked crowns. The legs, feet, and base of the bill are dusky-red. Juveniles acquire adult-like plumage the following summer.

Black skimmers are notable for their long, laterally compressed bill, which has a lower mandible, or jaw, that extends beyond the upper mandible. Gull-like, with narrow, tapered wings, the black skimmer is graceful and buoyant in flight. Its call is a distinct, repeated barking.

Distribution & Habitat

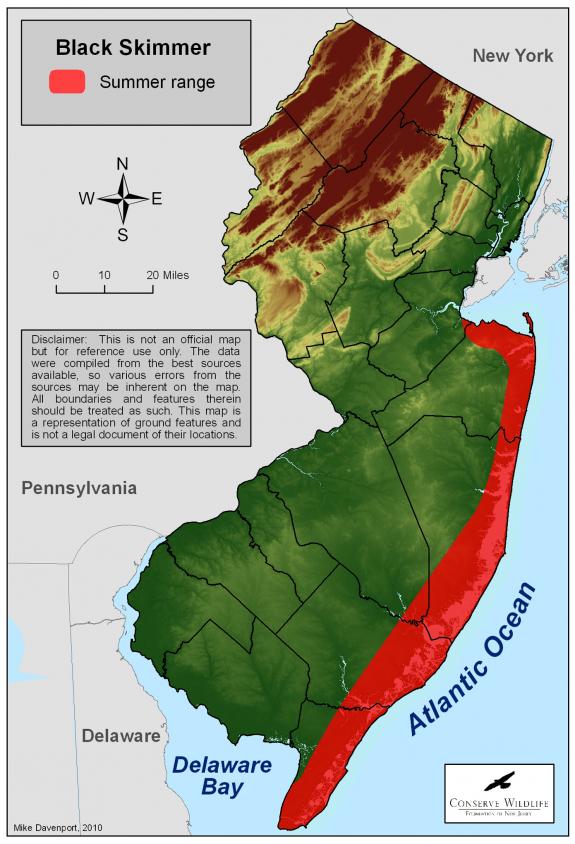

In New Jersey, black skimmers nest along the Atlantic Coast from Sandy Hook to Cape May.

Fall migration of black skimmers in New Jersey occurs from mid-August through October, with a few individuals seen into November. Wintering skimmers are very rare in the state. Spring migration occurs from mid-April through May.

The black skimmer nests on open sandy beaches, inlets, and offshore islands with sparsely vegetated and shell fragments. The growth of dense vegetation may cause colony relocation. Skimmers often nest on wrack mats (deposits of dead sea grasses and other vegetation) on marsh islands in the back bays; however, these colonies are typically much smaller than the beach colonies. Black skimmers forage in shallow-water tidal creeks, inlets, and ponds. Similar coastal and estuarine habitats are used throughout the year.

Diet

The diet of the black skimmer consists primarily of small fish such as minnows, killifish and herring. Shrimp and other crustaceans make up the remainder of the diet. Its unique hunting method has earned the skimmer its name. The skimmer glides low over the water, allowing its lower mandible to slice the water’s surface. When the bird’s bill strikes a fish, it snaps shut. The skimmer then aligns the prey headfirst before swallowing it whole. Skimmers may hunt during the day or at night, as foraging activity is correlated with tidal cycles. Foraging activity peaks near and during low tide.

Life Cycle

From late April to May, black skimmers arrive on their breeding grounds. Skimmers nest in colonies from a few pairs to several hundred. They return each year to areas where they have experienced past reproductive success, provided that suitable habitat remains. Often, nests are located within colonies of common and least terns, which nest earlier than the skimmers. Prior to copulation, the male skimmer presents his mate with a fish. Both the male and female dig shallow scrapes in the sand, one of which will be selected as the nest.

From mid-May to early June, the female lays a clutch of two to six eggs. Skimmers may replace lost clutches, particularly those destroyed by flooding. Eggs may be laid as late as September, although they are unlikely to be successful. Sandy-colored with brown speckling, the eggs are well camouflaged within their scrape nest. Both adults incubate the eggs fro 21 to 25 days, and they hatch during mid- to late June. By two weeks old, the young are able to elude predators. Young chicks are fed by their parents, but receive whole fish as they grow older. Initially, both the upper and lower mandibles of the bill are equal in length on young skimmers. The bill appears adult-like, with a longer lower mandible, by the time they fledge at 23 to 26 days.

If a predator or intruder threatens the colony, adults of both skimmers and terns take to the air and aggressively mob the intruder. Adult skimmers may also perform a broken wing display, feigning injury to lure predators away from the nest. Skimmer chicks may hide among vegetation or lay flat in the sand, camouflaged by their plumage. After fledging in mid-July to early August, they remain in flocks prior to fall migration.

Current Threats, Status, and Conservation

Each year, the New Jersey Endangered and Nongame Species Program (ENSP) monitors the state’s black skimmer population. Nesting colonies are enclosed and patrolled by personnel. Counts of adults and young are conducted to monitor population size and productivity. Despite annual fluctuations, the state’s breeding population has remained relatively stable since the its original listing, although the number of active colonies has declined significantly. Human disturbance, beach raking, tidal flooding, and predation still threaten nesting skimmers and their habitat.

Human disturbance, degradation of nesting habitat, tidal flooding, and predation limit black skimmer breeding populations in New Jersey. Elevated levels of human activity at beaches may cause colony abandonment, lower nesting success, and increased predation risk. The skimmers; well-camouflaged eggs and chicks are susceptible to trampling by vehicular or foot traffic in nesting areas. Disturbance from people walking near or through nesting colonies, may cause adult skimmers to flush from their nests to drive intruders away. While the adults are away from the nest, the chicks are vulnerable to predators, temperature stress and displacement. Defense displays conducted by adults may alert predators and attract them to eggs and/or young. Predators of skimmers and their eggs include rats, laughing gulls, dogs, raccoons and among others. High levels of predation can cause site abandonment and nesting failure.

Coastal beaches have been degraded due to heavy recreational pressure. The use of vehicles on beaches creates ruts in the sand, where chicks may become trapped. The great volumes of people at the Jersey Shore during the summer months has forced skimmers to nest in remote, low-lying areas where they are more susceptible to tidal flooding. Flooding can result in washouts of nests, eggs, and young of entire colonies. The erosion of coastal beaches intensifies the threat of flooding.

Black skimmers may be affected by environmental contaminants such as pesticides and metals, which are acquired in their diet. In addition, oil spills may impact skimmers that ingest oil while skimming for food. Skimmers bathing or wading in contaminated water may ingest oil during preening.

The ENSP conducts active management for beach-nesting birds, including black skimmers, each year. Prior to the arrival of nesting birds, known breeding sites are enclosed with fencing (posts and string). In addition, areas of suitable habitat and new breeding sites may be enclosed to encourage nesting. Nesting colonies are posted with educational and restricted-access signs. Personnel patrol skimmer colonies to reduce human disturbance and to educate the beach-going public. Biologists also conduct counts of nesting adults and young.

Learn about the work being done to research and protect NJ’s beach nesting birds at our Beach Nesting Birds Project webpage.

Scientific Classification

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Aves

- Order: Charadriiformes

- Family: Rynchopidae

- Genus: Rynchops

- Species: R. niger