Strix varia

Type: bird

Status: threatened

Species Guide

Barred owl

Strix varia

Species Type: bird

Conservation Status: threatened

On still spring evenings, the hooting and eerie caterwauling of barred owls resonates throughout remote, swampy woodlands in New Jersey. The resounding song of the barred owl, often represented as “who cooks for you, who cooks for you allll,” is often accompanied by a loud “hoo-ah” calls and yowling reminiscent of monkeys. Barred owls may vocalize throughout the year, but are most expressive during courtship, from late February to early April. These owls may call at night or during the day.

The barred owl is a large fluffy-looking owl with brown barring on the upper breast and brown streaking on the lower breast and belly. The round head lacks ear tufts and the eyes are dark brown.

Distribution & Habitat

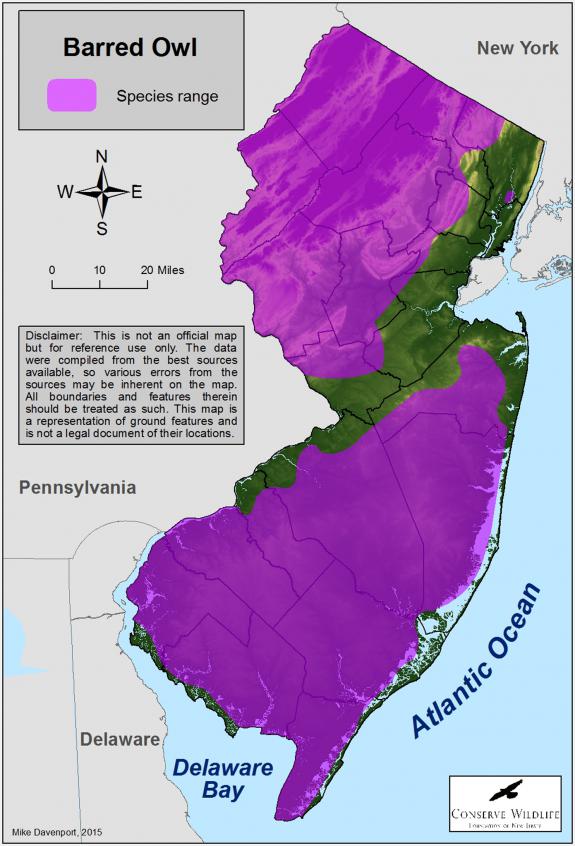

The barred owl occurs throughout the eastern United States north to southern Canada and south to the Gulf Coast and Florida. It is a year-round resident (does not migrate) that is widely distributed throughout wetland forests in southern New Jersey and riparian woodlands in northern New Jersey. Considerable populations of barred owls occur in the Highlands region of north Jersey, the Pequannock watershed, High Point State Park, Sterling Forest, Wanaque Wildlife Management Area, the Passaic River basin, and Great Swamp National Wildlife Refuge. In south Jersey, populations occur at Bear Swamp Natural Area, Belleplain State Forest, Great Cedar Swamp, and along tributaries of the Maurice River. In the Pine Barrens region, barred owls are restricted to Atlantic white cedar swamps and mixed hardwood swamps.

Traditionally known as the “swamp owl”, the barred owl is a denizen of remote, contiguous, old-growth wetland forests. These owls require mature wetland woods that contain large trees with cavities suitable for nesting. Barred owls are typically found in remote, wilderness areas that may also contain other rare species such as the red-shouldered hawk or the Cooper’s hawk. Barred owls typically shun human activity by avoiding residential, agricultural, industrial, or commercial areas.

In southern New Jersey, barred owls inhabit both deciduous wetland forests and Atlantic white cedar swamps associated with stream corridors. Often such lowland forests are buffered by surrounding pine or pine/oak uplands that may protect the owls from human disturbance and provide additional foraging habitat. In northern New Jersey, barred owls inhabit hemlock ravines and mixed deciduous wetland or riparian forests. Barred owls prefer flat, lowland terrain and avoid rocky slopes and hillsides.

Diet

The diet of the barred owl consists predominantly of small mammals but may also include reptiles, amphibians, insects, or small birds. Prey items are swallowed whole and are later regurgitated as pellets of undigested bones, fur, and feathers. Feeding areas, which are often littered with pellets and whitewash, are telltale signs of an owl’s presence.

Life Cycle

From late February to mid-April, calling barred owls strengthen pair bonds and reinforce territories. A courting male and female bow toward each other with wings fanned out, while rocking their heads from side to side. Vocal activity peaks during March, when the noisy, cackling calls of these owls can be heard echoing throughout their deep, swampy haunts.

Barred owls exhibit strong pair bonds and site fidelity. Consequently, a pair often occupies the same territory or nest in successive years. Large cavities within dead trees or dead limbs of live trees serve as nesting sites. Nesting trees must be large enough to provide cavities of adequate size.

From March to mid-April, females deposit two to three round, white eggs within the unlined nesting cavity. The male delivers food to the female who incubates the eggs for 28 to 33 days. The young are brooded until they are nearly three weeks old. Both adults care for them, providing the nestlings with pieces of meat. At four to five weeks of age, the fledglings vacate the nest, branching out onto nearby limbs. At about six weeks, the young are able to fly but may continue to be fed by their parents.

Current Threats, Status, and Conservation

The barred owl was traditionally a common resident within the deep, wooded swamps of New Jersey. By the early 1940s, the cutting of old growth forests and the filling of wetlands greatly reduced habitat throughout the state. Habitat loss and associated barred owl declines continued for the next several decades. Due to population declines and habitat loss, the barred owl was listed as a threatened species in New Jersey in 1979.

The loss, alteration, degradation, and fragmentation of forested habitats are the primary threats facing barred owls in New Jersey. Cutting of dead trees, thinning of forests, and controlled burns may eliminate nesting cavities or render sites unsuitable for breeding barred owls. Barred owls require large expanses of mature forests, and are adversely affected by forest fragmentation. Within fragmented woodlots, barred owls are increasingly vulnerable to human disturbance and predation by great horned owls.

References

Text derived from the book, Endangered and Threatened Wildlife of New Jersey. 2003. Originally written by Sherry Liguori. Originally edited by B.E. Beans & L. Niles. Edited and updated in 2010.

Scientific Classification

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Aves

- Order: Strigiformes

- Family: Strigidae

- Genus: Strix

- Species: S. varia