Terrapin Week: Viewing Terrapins!

How to See Terrapins in the Wild in New Jersey

This story marks the third of five blog stories spotlighting New Jersey’s Diamondback Terrapin – and educating people on the research and efforts being done to protect these fascinating reptiles!

Part 1, Monday, was an introduction into the world of the Diamondback Terrapin. Part 2, Tuesday, featured CWF’s research efforts to protect the terrapins. Part 3, today’s blog post, will look at great places to view these beautiful turtles. Part 4, Thursday, will highlight some important ways you can help protect the Diamondback Terrapins. Part 5, Friday, will showcase some other important regional research being done by our partners.

by Ben Wurst

During their nesting season, Northern diamondback terrapins are usually pretty easy to spot along the coast of New Jersey, and throughout their range. They are beautiful turtles with very unique coloration.

Individuals vary in coloration, but in general, their upper shell, or carapace, is dark with a diamond shaped pattern on it. Their lower shell, or plastron, is a light yellow/green color. Their skin is a grey color with black spots that vary highly between individuals. Almost all have a light upper mandible.

From May through July, spotting a terrapin is pretty easy!

Females leave the protection of the coastal waterways to find suitable nest sites to lay eggs. They seek areas with sandy soil, like dunes, parking lots and road shoulders. When our barrier islands were developed, roads were created to access those islands.

The creation of these roads also increased the amount of available nest sites for terrapins. But the development itself actually decreased the amount of suitable nesting habitat for them overall. Much of our coast is now bulkheaded.

Bulkheading restricts the natural movement of terrapins and limits their ability to find suitable nest sites. So, now they must take what they can get: roadsides. Nesting on the edges of roads is a perilous journey for terrapins. The vehicles that travel on those coastal roads may have careless drivers behind the wheel.

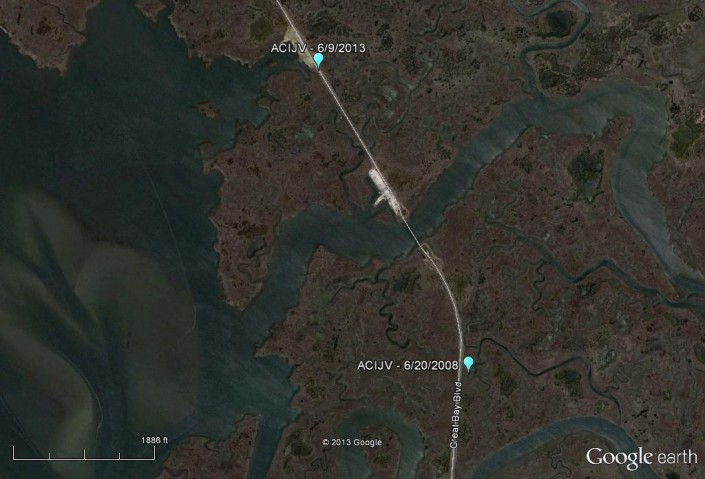

Terrapins may be found in many different places along the coast, especially roads that criss-cross saltmarsh. Use extreme caution in trying to spot terrapins on active roads used by vehicles – not only to avoid driving over terrapins, but for your own safety and that of other drivers or pedestrians.

Some widely used locations include Avalon Boulevard and other west-east highways connecting the mainland with barrier islands and peninsulas. Many coastal areas in Cape May also feature high numbers of terrapins, while Monmouth County, Ocean County, and Meadowlands coastal regions feature plenty of terrapins as well.

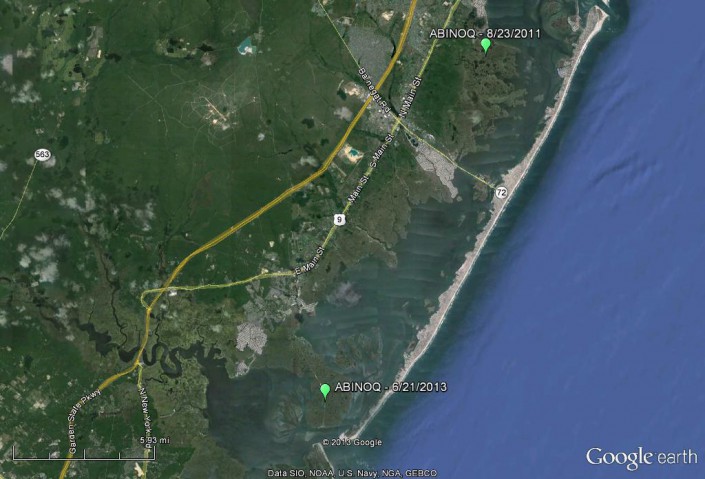

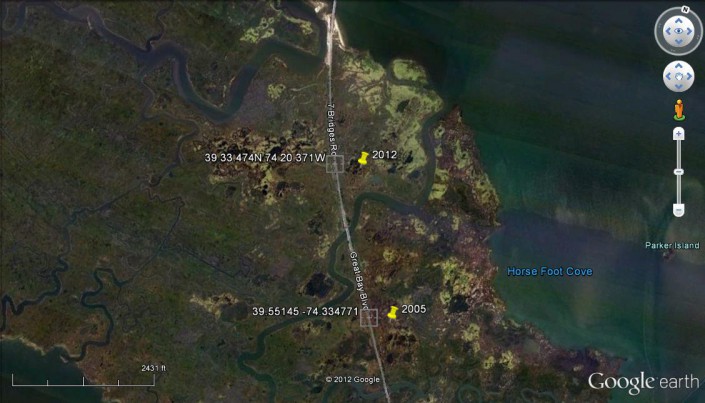

However, one of the best places to view terrapins during their nesting season is inside the 5,000+ acre Great Bay Blvd. Wildlife Management Area, Little Egg Harbor, NJ. The WMA is located along the coast and is accessible by motor vehicle from the 5 mile long road that ends at the Rutgers Marine Field Station. The road was originally planned to connect the mainland with Atlantic City in the early 1900s. Luckily that plan fell through and the last bridge was never built (road is also called 7 Bridges Road, after the 7th bridge that was never built). There is plenty to see and do out on GBB, at all times of the year. A wide variety of wildlife can be observed from the road, including ospreys, terns, oystercatchers, herons, egrets, and shorebirds. Lots of outdoor recreation opportunites await as well, including crabbing, fishing, and kayaking. There are boat ramps along the road, and all the owners of the local marinas are very nice, including Capt. Mike’s, Rand’s Boats, and Cape Horn Marina.

Viewing terrapins:

Terrapins can be timid if approached, especially when nesting. Please keep your distance when near a nesting female. You wouldn’t want to cause a female to abandon laying eggs in a nest cavity! If she is unable to cover up her eggs with soil then they might become an easy meal for a gull or crow… Watching them nest is fun to watch as they excavate down and lay 8-12 eggs.

If you see one on the road and there is no traffic, slow down or stop and let it cross. If there is traffic coming, stop your vehicle, put on your hazard lights and carefully get out and move the terrapin in the direction it is heading. Terrapins can bite, so be careful and pick it up from the side of it’s shell (called the bridge). Use 1-2 hands to ensure you have a good grip. Sometimes they use their legs to try and get you to let go! Put it on the soft shoulder to be out of harms way. If you have a GPS or a smartphone, record the location and submit us a sighting via our online terrapin sighting form. Data collected from the form will help guide future conservation efforts for them in NJ.

Other great viewing areas:

- Gateway National Recreation Area – Sandy Hook Unit

- Island Beach State Park

- Edwin B. Forsythe NWR – Oceanville

- Wetlands Institute – Stone Harbor

- Reeds Beach

- Fortescue Beach

Ben Wurst is a wildlife biologist for Conserve Wildlife Foundation of New Jersey.