International Migratory Bird Series: Great Blue Heron

CWF is celebrating International Migratory Bird Day all Week Long

by Lindsay McNamara, Communications Manager

CWF’s blog on the great blue heron is the fourth in a series of five to be posted this week in celebration of International Migratory Bird Day (IMBD). IMBD 2016 is Saturday, May 14. This #birdyear, we are honoring 100 years of the Migratory Bird Treaty. This landmark treat has protected nearly all migratory bird species in the U.S. and Canada for the last century.

Have you seen a great blue heron wading in the marshes of the Garden State? While they are commonly seen along shorelines, river banks, and the edges of marshes, estuaries, and ponds, the breeding population of these wading birds is actually listed as a Species of Special Concern in New Jersey.

The term ‘Species of Special Concern’ applies to wildlife species that warrant special attention because of some evidence of decline, inherent vulnerability to environmental deterioration, or habitat modification that would result in their becoming a Threatened species.

Due to its wide distribution, varied diet, and flexibility in nesting near both freshwater and saltwater environments, the great blue heron’s population in North America is stable. However, wetland destruction in New Jersey has caused a decrease in heron populations from their historic numbers. Since the 1950s, habitat loss has occurred at an alarming rate in New Jersey, destroying wetlands critical to breeding herons.

Protecting our wetland habitats from disturbance and development will help protect the great blue heron, the largest wading bird in North America. Great blue herons are 46 inches long and have a wingspan of 72 inches. Despite their large size, great blue herons only weigh 5 to 6 pounds, in part because of their hollow bones — a feature all birds share.

Great blue herons can hunt during the day and night, thanks to a high percentage of rod-type photoreceptors in their eyes that improve night vision. They eat nearly anything within striking distance, including fish, amphibians, reptiles, small mammals, insects, and other birds. Herons nest in colonies or “rookeries” in tall trees near bodies of water.

The oldest great blue heron on record was found in Texas when it was at least 24 years, 6 months old!

The great blue heron occurs throughout most of North America, from Alaska and eastern Canada in the north to the northern portion of South America in the south. Northern populations of great blue herons east of the Rockies are migratory.

The great blue heron occurs throughout most of North America, from Alaska and eastern Canada in the north to the northern portion of South America in the south. Northern populations of great blue herons east of the Rockies are migratory.

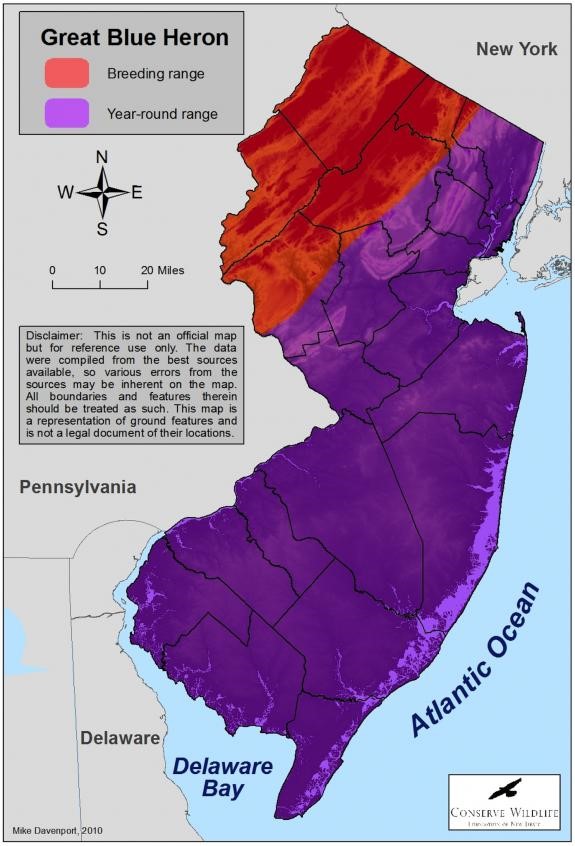

They withdraw from the northernmost portion of their range during the winter, some traveling to the Caribbean, Central America or northern South America. This species breeds throughout New Jersey. They generally do not occur within the northwestern corner of the Garden State during winter. Great blue herons migrate singularly or in small flocks, mainly in daytime.

We still have much to learn about the biology and population status of great blue herons in New Jersey. Research needs to be conducted to find additional breeding sites, check existing nesting areas, and determine whether the population might be decreasing or increasing. You can help! Next time you see a great blue heron in the Garden State, be sure to submit a Rare Species Sighting form.

Learn More:

Lindsay McNamara is the Communications Manager for Conserve Wildlife Foundation of New Jersey.

Discover more from Conserve Wildlife Foundation of NJ

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.