The Double-edged Sword of Reptile and Amphibian Accessibility

by Christine Healy, Wildlife Biologist

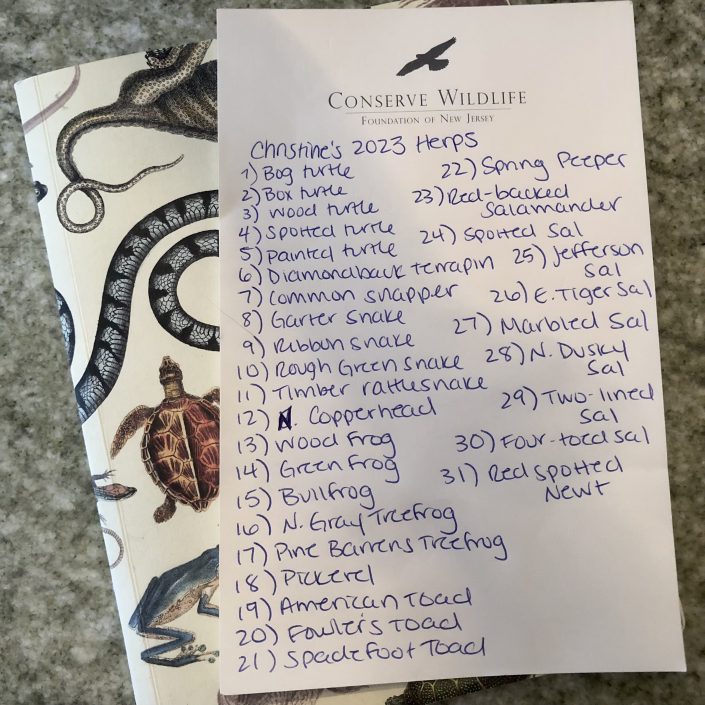

Although I spend much of my time thinking about reptiles and amphibians, if you were to ask me if I could be classified as a “herper”, my immediate answer would be no. When I go for hikes, my objective is to reach the summit and take in the view- I’m not generally looking to offroad and go slow. I recently compiled a list, however, of all the herps that I have found during my outdoor adventures this year and was shocked to realize that I’ve encountered 31 species of wild turtles, snakes, frogs, and salamanders. Of those, I had the intention of locating 13 as part of my seasonal field assignments for CWF- the rest were all incidental finds. Moreover, despite the period in question being rather lengthy, it was very easy for me to parse apart which species were really 2023 observations versus some other year. And I can recall where I was and what the individual was doing in each case.

When I tried to complete the same exercise for other groups of wildlife, I found it much more difficult. Maybe it’s a numbers game… I’m sure my bird count would be well above 31 for 2023, but I found myself adding species simply because of thoughts like “I’ve probably seen a cormorant this year” without any real memory of doing so. Perhaps it’s just inherent bias… it’s my job to notice reptiles and amphibians, after all. But I don’t think so. Before CWF, I worked with mammals and was sure that I would continue to do so throughout my career. I love them just as much as ever, though I can’t tell you when exactly I spotted that coyote, or what behavior the cottontail was engaged in. No, I think that my vivid memory of herp experiences has to do with something else entirely. Proximity.

Of the 31 species included in my tally, my observation distance was less than three feet from all but two; I felt the timber rattlesnake and the northern copperhead might appreciate some extra space. That said, the rattlesnake was so well camouflaged in the surrounding leaf litter that it took almost stepping on it to see it, so perhaps that doesn’t count. The birds and mammals that have been within that radius are restricted to the house finches, house sparrows, and cardinal that visit my bird feeder and the squirrel that ventures onto my porch to antagonize my cat. Chances are that if you’ve seen any reptiles or amphibians this year (apart from pond turtles), it has been because you have been similarly close to them. And when you’re that close to wildlife, how can you resist spending some time and engaging with them?

This reality presents something of a double-edged sword for our local herps. On the one hand, their accessibility and (generally) docile nature renders them ambassadors for wildlife conservation. Jane Goodall once said “Only if we understand can we care. Only if we care will we help. Only if we help shall they be saved.” Herps are often the first group of animals that children have the opportunity to observe in nature. When people learn what I do, they almost invariably have a story to tell me about frogs or turtles from their youth that is still special to them 20, 40, even 60 years later. When I lead toddler hikes for my local parks system, I love watching the kid’s faces light up when I lift a trail-side rock and uncover a red-backed salamander or a garter snake. There is no fear, no sense of ownership, just a genuine thrill of sharing the world with creatures so very different from us.

But on the other hand, this magical quality ultimately introduces a host of threats to herps. It can be easy to injure them through this closeness. They can be accidentally crushed when we utilize trails- either by foot or recreational vehicle. We can introduce diseases and damage their skin by handling or walking through the sensitive habitats they depend on. Some folks believe that their inability to get away means that it’s fine to take them home. Additionally, their ability to blend in until they move can be startling- and sadly opens the door for intentional killings.

As part of a conference that I recently attended, the organizers hosted a round table discussion on ethical herping. The American Birding Association has established a moral code for hobbyists to ensure limited impact on birds during observation. Such a document does not currently exist for herps, but the Northeast Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation (NEPARC) group believes that it should. How to go about writing it, however, is a complicated question. The way that we interact with reptiles and amphibians is simply different than the way we interact with birds. The threats they face are also different. The round table discussion illuminated many and diverse opinions on how to herp ethically and sadly time ran out before we could really begin to formulate a framework for a future guidance document. I feel confident that this subject will be raised at the next NEPARC meeting.

For my part, I think my guidelines for ethical herping would look something like this:

- Handle amphibians and reptiles only when necessary and make sure you do so in a manner that is safe for both you and the animal in question. Beyond handling technique, also consider if you may have anything on your hands (lotions, cleaning products, pathogens acquired from handling sick individuals, etc.) that could be harmful to them. If you think you might, don’t touch!

- Do your research beforehand and be able to recognize signs of distress. If a reptile or amphibian is indicating that they are unhappy, back off and give them their space.

- Maintain the quality of the habitat! If you are rolling logs, do so gently and always put them back in place.

- Share your enthusiasm with others, particularly children. Introduce them to the exciting world of reptiles and amphibians but instruct them on how to do it with care. Looking at a frog or salamander can still be a thrilling experience for a kid- they don’t need to be holding it to become an ally and a voice.

- Remember that poaching is a serious threat for many of our native species- especially turtles and snakes. Avoid disclosing locations when sharing photos of these animals online. You never know who that information will reach.

- Never remove a reptile or amphibian from the wild, unless they are injured, and you are bringing them to a licensed rehabilitator.

- If you herp regularly, bookmark the NJ Wildlife Tracker app (https://survey123.arcgis.com/share/ae6c1dbdacd94562a25785433f612750) on your phone. These animals can be very difficult to survey, so if you come across a rare species, you can play a role in their protection by reporting them to the Division of Fish and Wildlife.

Are you a herper? If so, I’d love to hear your insight on the topic of ethics and your own stories from the field in the comments!

Discover more from Conserve Wildlife Foundation of NJ

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Comment

Great idea. Next time we are hiking with the grandkids they make a list of what they see. A great idea even without the kids. A walk, see, identify what you find.

Comments are closed.