The Complicated History of Our Marshes and an Update on Restoration Progress

by Caroline Abramowitz, CWF Biological Technician

When looking at the expansive mudflats along the marshes of the Delaware Bay, it is hard to imagine that the area was once densely vegetated and home to a variety of bird species. This spring, CWF began work on a new marsh restoration project funded by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and led by Ducks Unlimited and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). CWF was contracted to assist with biological monitoring at sites targeted for marsh restoration along New Jersey’s side of the Delaware Bay. Restoration efforts for our sites are being directed toward mudflats that exist due to significant physical alterations made to the marsh in the past. The story of how these mudflats came to be lies in the area’s history and roots in salt hay farming.

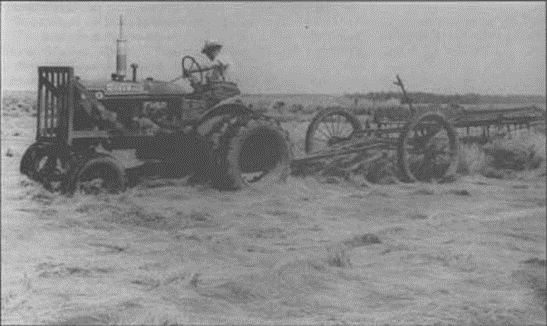

As early as 1675, settlers arriving on the Delaware Bay built dikes in salt marshes to protect land from saltwater inflow and create an environment more conducive to salt hay farming and development. One of the most important types of salt hay harvested along the Delaware Bay was Spartina patens, a crop that was widely used as bedding and feed for livestock due to its high nutritional value. By the mid-1800s, at least 14,000 acres of marsh were impounded in Salem County alone with comparable areas altered in both Cumberland and Cape May counties (Cook, 1870). Impoundments restricted tidal flow within the marsh, which stopped the natural process of marsh accretion in which sediment is consistently added to the marsh to increase its elevation. Additionally, drier conditions exposed marsh soil to too much air, resulting in the breakdown of soil and further loss of elevation.

Photo retrieved from”From Marsh to Farm: The Landscape Transformation of Coastal New Jersey,” by Kimberly R. Sebold.

Retrieved through https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/nj3/contents.htm

When economic conditions worsened in the mid-1900s, maintenance became too costly and impoundments breached as dikes were not continually restored to prevent water from flooding in. The impounded marshes had fallen to elevations that were unable to support vegetation as a result of these earlier farming practices restricting tidal flow and sediment accretion. As the marshes became inundated with water, plant species such as Spartina patens – a high marsh plant that requires higher elevation and can tolerate less flooding than low marsh plant species – were unable to survive. The results of this flooding and decline in marsh elevation are the bare mudflats we see today, stripped of many native species that are integral to its resiliency.

Salt hay farming is still an active practice, but to a much lesser extent. Spartina patens is harvested today for plant nurseries, road construction, and making rope. Although salt hay is an important natural resource to continue harvesting, wide expanses of mudflat along the Delaware Bay that are no longer used for farming have been unable to revegetate without intervention. This restoration project aims to improve the resiliency of the marsh by creating conditions that will raise elevation and encourage vegetation re-growth in the mudflat areas.

Maintaining a healthy salt marsh is important not only for stabilizing shorelines, but also for providing vital habitat for a wide array of marsh-obligate species. For example, higher elevation marshis crucial for the survival of species such as the Eastern black rail and saltmarsh sparrow. These birds rely on drier elevations and marsh plants like Spartina patens for nesting. Once common along the Delaware Bay, the black rail is now estimated to be locally extirpated within the next 50 years if interventions do not occur to restore marsh habitat (USFWS, 2020).

In coordination with our partners in the USFWS Delaware Bay Coastal Program, CWF is conducting avian and vegetation surveys, as well as nekton surveys to study the actively swimming aquatic organisms that utilize our marsh. Pre-restoration monitoring such as this helps our partners understand the conditions of future restoration sites and provides valuable baseline information against which post-restoration data can be compared.

Although this work has been an exciting step towards the long-term goal of cost-effective and low-tech saltmarsh restoration, the day-to-day marsh work has been a lesson for us in adaptability and collaboration. Our primary focus thus far has been conducting point count avian research surveys. These surveys involve the use of a speaker that starts with 5 minutes of silence and then plays 8 minutes of secretive marsh bird calls at regular intervals. Some of the more elusive birds will hear the speaker playing the call of an inter- or intra-species competitor and respond. This allows us to determine the presence of some rarely seen birds such as American bitterns and clapper rails (who often responded loudly and proudly to our recordings). These surveys can be tricky as we are responsible for counting all birds seen or heard while keeping track of the birds’ distance and movements, thereby ensuring that no individual was recorded twice. It was a challenge to rewire our brains and estimate the locations and distances of six clapper rails all calling simultaneously, while keeping track of whether there are 10 or 11 marsh wrens fluttering around in the reeds.

Photo courtesy of Kaity Ripple, USFWS

Additionally, our pre-monitoring surveys often had very specific timing requirements. Surveys needed to be completed at high and low tide, early in the morning, and on days with low wind and clear visibility (i.e., no fog or smoke). Additionally, unlike our rail friends, humans were not graced with the ability to run through dense marsh vegetation. As you can probably imagine, some of our sites were challenging to access and navigate. We often found ourselves trudging through tall marsh grass and mud at 5am only to find that one of the survey points was simply inaccessible without getting permanently stuck in waist-deep mud or stranded in the marsh as the tide came in.

Despite these challenges, we were able to collaborate with our partners and figure out effective ways to access our sites by carefully navigating boats through abandoned wooden structures in the waters and keeping our spirits high by competing in “BIRDO” (like bingo but instead of numbers you need to check off species of birds you see in the marsh). We grew accustomed to strategically traversing particularly mucky sections of the marsh on foot and conducted surveys from kayaks when high tides made walking in the marsh challenging. We learned a lesson in adaptability and gained an even greater respect for the resilient wildlife that call the marsh home and navigate this ecosystem every day. We’re excited to continue more vegetation and nekton surveys in the upcoming weeks as we work towards helping to restore some of our beautiful salt marsh habitat.

Sources:

Cook, G.H. (1870). Annual Report of the State Geologist of New Jersey, for 1869. New Jersey Geological Survey, Trenton, NJ.

Fish and Wildlife Service (2020). Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Threatened Species Status for Eastern Black Rail With a Section 4(d) Rule. Federal Register, 85(196).

Discover more from Conserve Wildlife Foundation of NJ

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Comment

Conserve Wildlife Foundation of New Jersey is an amazing resource and advocate for our lands and waters. The work they do helps everyone in the region and supports the world we love. Thanks for this great article on what some have called the earth’s lungs, our marsh lands.

Comments are closed.