Students partner with nonprofit Conserve Wildlife Foundation to design better bat houses

By Stephanie Feigin

Although bats have a reputation of being dangerous and scary, these flying mammals are something to be coveted, and the students at Princeton Day School know why. Seventh grade students Albert Ming, Arjun Sen, Martin Sen, Dodge Martinson, Kai Shah, and Samuel Tang teamed up with Conserve Wildlife Foundation to design a better construction plan for bat houses. The students hope to promote better conditions for bats living in Central Jersey.

Bats are in the midst of tragic declines as a consequence of habitat loss and a devastating fungal disease known as White-nose Syndrome. CWF works to preserve bats, which basically provide a free pest removal service. A single bat can consume up to 3,000 mosquito-sized insects in one night! Their value to agriculture is estimated at $53 billion annually in the United States alone. Not to mention they provide mosquito and biting insect control, which are not only a nuisance but also have disease spreading potential.

Many bats in New Jersey have come to depend on manmade bat houses, structures specifically designed and placed for the needs of the bats, and the Princeton Day School students stepped up to help.

First, the students researched the best, most economical type of wood to use for construction. Next, they used an infrared thermometer to see how well heat is absorbed and retained by the different wood types after they were painted and stained using three different colors.

Keeping the inside of a bat house within the right temperature range is vital to the survival of bats, especially the vulnerable young pups. If a bat house becomes too hot (above 95 degrees) or too cold (below 65 degrees), the health of the bats is threatened. Bats move their pups from house to house in search of the right temperatures.

The students used the results of their temperature experiment and high and low temperature readings for Central Jersey over the past three years to design a plan for a bat condo unit that would satisfy bats temperature requirements during their entire six month roosting period.

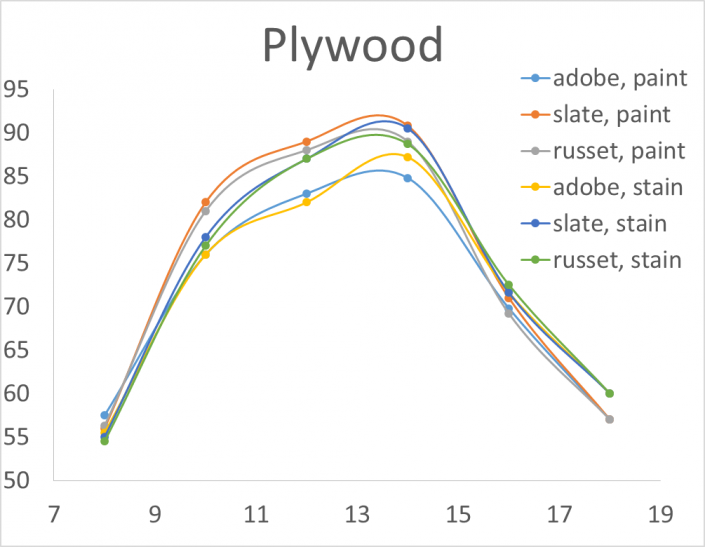

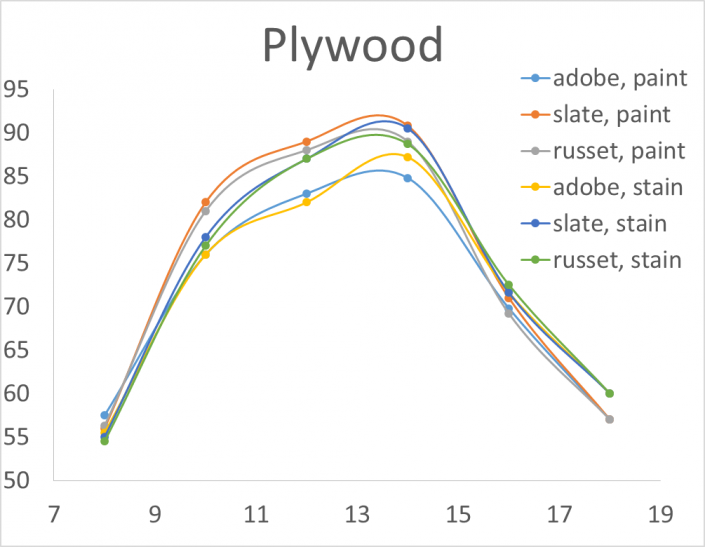

The x – axis is the number of hours passed during the day and the y- axis represents degrees Fahrenheit.

This graph displays the research for the best type of wood (cedar, pine or plywood) to use for constructing bat houses, along with different kinds of paint (adobe, slate or russet) to determine which combination could retain the most heat for the bat colonies. Heat retention was measured over a long period of time while exposed to the sun.

The research revealed that the bat houses are most successful if they are painted or stained and weather resistant wood like cedar would last much longer than softer wood like pine or plywood. When cedar wood was used the temperature changed the most as the air temperature changed and the least when sunset came. When plywood was used the temperature changed the least as the air temperature changed and the most when sunset came. When pine wood was used the temperature changed moderately as the air temperature and moderately when sunset came.

The conclusion made was that there are differences among wood and paint combinations. Adobe paint on plywood has the smallest average temperature change even though the difference is not statistically significant and adobe paint on cedar had the smallest temperature change between 4 and 6 degrees. They chose adobe paint on cedar or plywood as they are also the most cost effective.

With the results of their research and experiments, the students made informed decisions to design the bat boxes. The final product was three bat houses built using plywood. They painted one of the houses in a black slate color to provide maximum heat during the colder months, and painted a second house in an adobe beige color to provide air conditioning during the hot summer months. Lastly, they chose a russet color to for the moderate months.

CWF Wildlife ecologist Stephanie Feign who worked with the students on the project was happy to see how passionate these kids were to learn and be hands-on. “Their passion and enthusiasm were inspiring. Projects like these not only benefit wildlife, but also benefit surrounding communities and provide experiential learning for students.”

New Jersey is home to nine different species of bats, two of which are listed as endangered or threatened. Six species that do not migrate south for the winter remain in New Jersey to hibernate in a cave or another safe place. When they awake from hibernation in April, the females search for roosting spots to bear and raise their young pups. With so few intact forests in New Jersey, bats are struggling to find places to safely roost.

That is why projects like this one with Princeton Day School are essential for preserving bats. Not only did the projects help bats, but it also helped the students by requiring them to use problem solving and critical thinking skills to protect a creature that they came to value. Wildlife, which kids become excited and passionate about, is a valuable educational tool.

The team is currently working with Princeton Day School facilities to erect the bat condo unit on campus. Hopefully, by next spring, the school will be home to many new, very comfortable bats.

LEARN MORE:

Stephanie Feigin is a Wildlife Ecologist for Conserve Wildlife Foundation.