2015 Delaware Bay Shorebird Project Continues!

Another Season of the Delaware Bay Shorebird Project Underway

By: Dr. Larry Niles, LJ Niles Associates LLC

The value of a shorebird stopover like Delaware Bay can be seen in the shaky cam movie by this author. Red knots – some recently arrived after a grueling 6,000-mile flight over 6 days of continuous flying – arrive on the Bayshore desperate for food. Over the last 10,000 years, the species has evolved to fly directly to the Bay to feed on the eggs of the horseshoe crab.

The 450-million year-old crab – which is actually in the spider family – crawls ashore and lays pin-sized eggs about 6 inches deep in the sand. When there are many crabs, as here on Delaware Bay, one crab often unearths the eggs of another. Thus they leave millions of fatty eggs on the surface, offering an energy-rich, soft feast for the starving birds. In turn, we get to watch the birds racing for an egg ‘hot spot’!

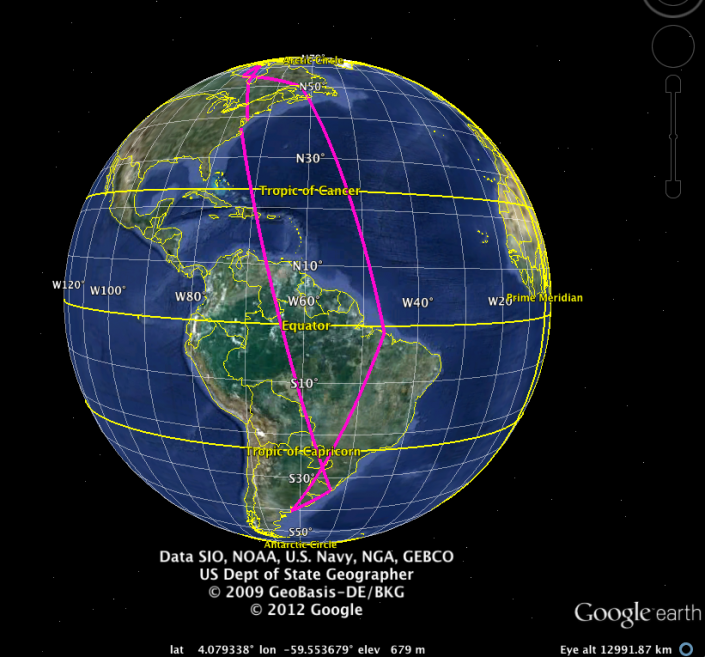

The birds often arrive beyond depleted. A normal weight for a knot is 130 grams. Many arrive on Delaware Bay below 100 grams, the equivalent of a human in the throes of profound starvation. But when the birds fly north from the coast of northern Brazil, there’s no turning back. Once they go, they must go all the way.

This year, migrating shorebirds faced a freak tropical storm that could have forced them out to sea, far off-course. In severe cases, some birds with no remaining fat reserves even metabolize their own muscles, like airplanes throwing out vital equipment to stay aloft. Storms can also prevent birds from lifting off on migratory flights. They are capable of detecting atmospheric pressure changes and can just stay put until a storm passes. We think this is what happened this week when a storm, followed by a strong cold front and consequent northwest winds, prevented a movement north.

The sum of these challenges was lower than normal shorebird numbers during the first week of the stopover. The Heislerville impoundments support a good number of short-billed dowitchers and dunlin, but these species usually arrive earlier than the others and probably came in ahead of the adverse winds. Yet there are very few ruddy turnstones, sanderlings and semipalmated sandpipers on the Bay.

The one exception on the Bay is the red knot. At first, we thought that only about 1,000 red knots had arrived in and around Reed’s Beach. Then Jerry Binsfeld and Peter Fullagar, Canadian and Aussie members of our team, found an amazing 7,000 knots at Gandys Beach on the northern Bayshore in New Jersey. Very likely, these are short-distance migrants, coming in from wintering areas in Florida, Georgia and the Caribbean.

Our catch results support this working hypothesis. The knots we caught at Fortescue were at higher weights than normal for this early part of the season, which would be expected if fewer very thin long-distance migrants were part of the average.

Discover more from Conserve Wildlife Foundation of NJ

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.