Shorebird Expedition Brazil: Investigating the plight of shorebirds and rural people

By Larry Niles, LJ Niles Associates LLC

We leave a cold and dark New Jersey with mixed feelings for our destination to tropical Brazil. It will be warm and sunnyish – though forecasts predict drenching thunderstorms threatening us every day of our trip. We will explore a very new place, the ocean coast of Para, a largely unsurveyed coast known to be a wintering shorebird mecca. At the same time, we will undergo trials experienced by few biologists. Zika is prevalent in Para, but recent cases of malaria are equally alarming. Of course, one must be ever vigilant for food and water pathogens. Last year, I developed food poisoning ending me up in a rural hospital, with a room full of very sick people. On arrival, I wondered what comes next?

The contrast of poverty and the truly wild can jar a Jersey biologist’s sensibility. People fall into poverty here because it’s the common condition. Poor sanitation, terrible roads, and nearly non-existing law enforcement plague those who live in coastal Brazil. The economic crisis and the ever-expanding corruption scandal in the federal government rob people of hope for the future and anchor them to a life of poor education and wages, and widespread filth. In the cities, the water churns with rubbish and contamination is ubiquitous.

Yet few people populate the ocean coast sites where we will survey. There, the sea teams with fish and shellfish beyond measure. Walking through a fish market is like going to a fish museum for all the species, exotic and common. Hundreds of small villages, most with only occasional power, perch precariously on the edge of this wonderful and largely uncontaminated sea or nestle deep in a vast mangrove forest, one of the largest in the world. In many ways it’s a biologist’s wonderland.

Only a few hundred miles away snakes the many channels of the Amazon River and surrounding it lies one of the world’s last great tropical forests. It’s the home of one of the great battlegrounds of environmentalism. The new U.S. administration will probably support the wealthy families cutting away valuable timber for cattle ranching, destroying carbon capturing and oxygen producing trees and, at the same time, the livelihood of native people who eke out a bare existence from rubber, nuts and the diverse wildlife that share the forest with them.

But our government has a lot to learn from the Brazilians. They have created a novel conservation system, one unknown to us in the U.S.

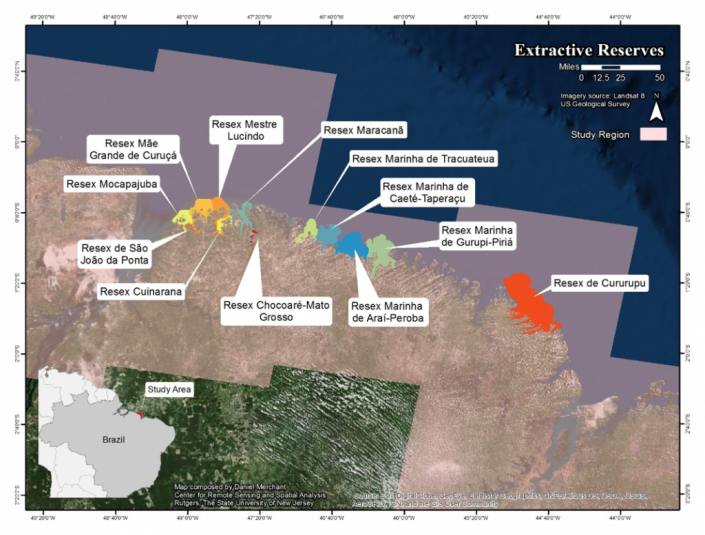

They call them extractive reserves. The federal agency in charge, ICMBio, struggles to save these reserves, not for tourists or rich residents, as we do in New Jersey, but for the people who live within. They stop the ranchers from destroying the forest. In the same way, they stop the international fishing fleets from decimating the fishery in Para. Staff of the agency die every year doing their job. One just recently in the state of Para, not far from our destination.

Our project aims to help. Our team, sponsored by Conserve Wildlife Foundation with Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation Act, will survey birds, measure habitat, and ultimately map this coast with state-of-the-art GIS system developed by Rutgers Center for Remote Sensing and Spatial Analysis. We intend to provide ICMBio staff with better GIS tools than are available in the U.S.

Over the next three weeks, we will be reporting on our research investigation. We will also explore the threats to the extractive reserves in our study area, everything from disturbance to shrimp farms.

For my part, however, I will also investigate if this system captures the best conservation envisaged by most religious leaders, including Pope Francis. Despite the political rhetoric of the old politicians that fill our media, most of the world’s religions speak openly about supporting climate change action. They envisage an “integral ecology”, in the word of Pope Francis, a union of the need to heal the earth and the plight of the poor. Even Southern Baptist have adopted this position that the impact of climate change falls on the poor. This is as true in Brazil as it is in Delaware Bay. Perhaps in Brazil lies a better way.

Dr. Larry Niles has led efforts to protect red knots and horseshoe crabs for over 30 years.

Discover more from Conserve Wildlife Foundation of NJ

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Comment

Larry,

I hope you are successful in your work in Brazil. It is an amazing country but the people are even more amazing. My wife, daughter and I have visited friends in Rio several times and they have come to New Jersey to visit us. They are always happy and upbeat. Brazil is in our hearts and souls.

I hope you will continue to up date your blog as I will follow it closely. In the spring I will look for red knots, ruddy turnstones and other shore birds when the horseshoe crab begin to lay their eggs in the Sedge Islands Marine Conservation Zone. Good luck with your work. Stay safe and try not to get sick.

Jim

Larry,

Good luck with the expedition although it sounds a little dangerous, especially to your health. Glad to hear that so many are in agreement with climate change, if only our present administration would be!!

Take care, stay vigilant and return home safely. See you in Greenwich.

Red and Mary Jane

Hi Larry,

I hope you and your team have a safe and fruitful trip. I was saddened to hear about the death of Luiz Alberto Araújo in the article link. Hopefully the Brazilian government can do more to protect heroes of conservation like him. Be safe !

Rick

Comments are closed.