Close to the Finish Line

by: Dr. Larry Niles of Wildlife Restoration Partnerships. Dr. Niles is working in Delaware Bay on behalf of Conserve Wildlife Foundation. He has helped lead the efforts to protect at-risk shorebirds and horseshoe crabs for over two decades.

Direct Flight to the Arctic or Stopover?

A migratory stopover for arctic nesting shorebirds must provide each bird the energy necessary to get to the next stopover or to the ultimate destination, the wintering or breeding area. Delaware Bay stands out among these shorebird refueling stops because it delivers fuel in the form of horseshoe crab eggs giving birds options. Our telemetry has shown that Red knots, the species we best understand, may leave Delaware Bay and go directly to their Arctic breeding areas, or stopover on Hudson Bay. The choice of going straight to the breeding area or stop at another stopover may be critical to understanding the ecological dramas now underway on Delaware Bay.

This year has been like none of the 23 years we have studied shorebirds and horseshoe crabs on Delaware Bay. Persistent northeast winds caused two unusual conditions that affected red knots and the other shorebirds species, ruddy turnstones, semipalmated sandpipers, dunlin, short-billed dowitcher, and sanderlings. First, the wind blowing in from the cold ocean chilled the bay and slowed the horseshoe crab spawning to nearly a standstill until the last week of May. Whereas in other years, we would have seen tiny ribbons of eggs threading the tideline, this year we have none. Shorebirds depend on this natural largess, gobbling eggs with almost no effort and laying down weight like starving people at a fast-food restaurant.

Instead, this year they must hunt them down by scouring the bay for any odd pockets of crab spawning. Not only is there not enough, but the search burns valuable energy reserves that should ultimately go to the flight to the Arctic and breeding.

The second impact of the odd weather events of May came when Tropical Storm Arthur pounded the Southeast coast and generating a prevailing northeast wind along the entire coast. This blocks migration north. We can only guess this impact because COVID19 precautions prevented us from attaching tracking devices on red knots stopping over in Lagoa de Peixe in southern Brazil. Like Delaware Bay, LDP prepares birds for a long flight but to Delaware Bay. We have tracked red knots flying nonstop for almost 6 days to reach Delaware Bay. Attaching nanotag transmitters in Brazil would have helped us understand the impact of the storm on the birds. Instead, we must guess to what extent tropical storm Arthur impaired migration.

By the Numbers

We can usually figure out the Delaware Bay stopover story through numbers, but this year added a new twist that came with significant uncertainties. We typically see the first flock of red knots by May 12, a second, and a more significant influx the following week and nearly all by May 23. So last year, for example, we saw about 3000 knots, then 12000, and finally 30,880.

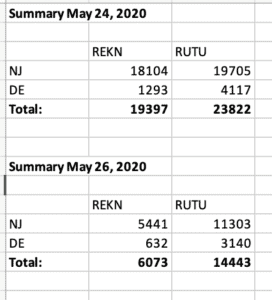

In contrast, this year, we only saw a few hundred by May 12, and by May 23 we never had more than a few thousand in each state. We judged this a consequnce of the Tropical Storm delaying shorebird arrivals. Surprisingly when we did our first baywide count counters in NJ and DE found 19,397 knots. Did these birds arrive, or had we missed them?

The answer came by May 26 when we did our second all bay count ( only 2 days later) and found only 6000 knots. Our subsequent search turned up less each day. Today we saw about 200 on the NJ side. This suggests that not only had the large group left but so did all the others.

At the same time, all of this was happening on the bay, we also saw 6500 red knots roosting in Stone Harbor during the second week of May. That number dropped to 2000 then finally to about 500. Were these part of the birds found in the May 24th survey? We have also received reports of Red knots in other places along the Atlantic Coast NJ, like Malibu Beach NJ and Forsythe USFWS Refuge suggesting birds moved from the bay to Atlantic Coast sites where they could feed on clams and mussel spat. Although sufficient for birds needing only modest weight gains, it is unlikely to satisfy the needs of the long-distance knots that must recover large amounts of weight to continue their migratory flight.

Leaving Delaware Bay for Other Places

From all this, we conclude the pulse of birds, seen in our first count came late to the bay were delayed by Tropical Storm Arthur, arrived and found few eggs, then left for other places along the Atlantic Coast.

Still, the departure puzzles us. Weather slowed crabs spawning until four days ago, and then water warmed enough to stimulate dense crab spawning in more areas and higher numbers. The last few days have been epic, as though the delay had pent up the need to spawn. Crab digs now pockmark most beaches and shoals. Our egg count shows this sudden increase starting at about May 24. The bay water temperature at the Cape May Bouy explains this change in spawning intensity. It showed water temperature reaching the threshold to elicit a good spawn at about the same time we saw more spawning and counted more eggs.

Yet, most beaches remained empty of birds. We made a catch of red knot on May 27, from among a very small group of knots. This sample would describe the weight gained by red knots that had been in the bay for the last few weeks. 70% of the red knots weighed less than what they need to fly to the Arctic and successfully breed or 180 grams. Yet all are gone by today May 29th.

So Why Leave?

So why did they leave? The scientific literature points out that when migratory birds arrive in a foodless stopover, they leave for another. The rule is ironclad. Get to the breeding areas in as little time as possible. When facing beaches devoid of eggs, it’s apparent the birds choose to move on. Too bad they did so just prior to the emergence of abundant horseshoe crab eggs.

Fortunately, these unfortunate birds still have options. They can stopover in one of the Hudson Bay stopovers, as I described in the beginning. Even then, they can choose not to breed and turn around. They also may die as we demonstrated in this paper by Sjoerd Dujins

There is still the possibility of birds arriving late. Our work will continue until the bitter end. If late birds arrive, we will know.

Discover more from Conserve Wildlife Foundation of NJ

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.