Plover Power

Reflections Three Years into the Shorebird Sister School Network Program

by Stephanie Egger, Wildlife Biologist

As we begin to wrap up our third year of the Shorebird Sister School Network, we are able to reflect on how far we have come in just a short time. In our first year, we started with just one class at Amy Roberts Primary School (Green Turtle Cay, Abaco, The Bahamas), led by teacher Jan Russell, which was paired up with a class at Ocean City Intermediate School (Ocean City, New Jersey), led by teacher Deb Rosander. We presented the students with information on the full life cycle of the Piping Plover, commonly referred to as “our birds” in New Jersey. Really they are residents of The Bahamas, spending over half their life on the warm sandy beaches surrounded by turquoise water. Piping Plovers in The Bahamas, in most cases, see less disturbance than what is experienced by plovers on their breeding grounds in the United States and Canada.

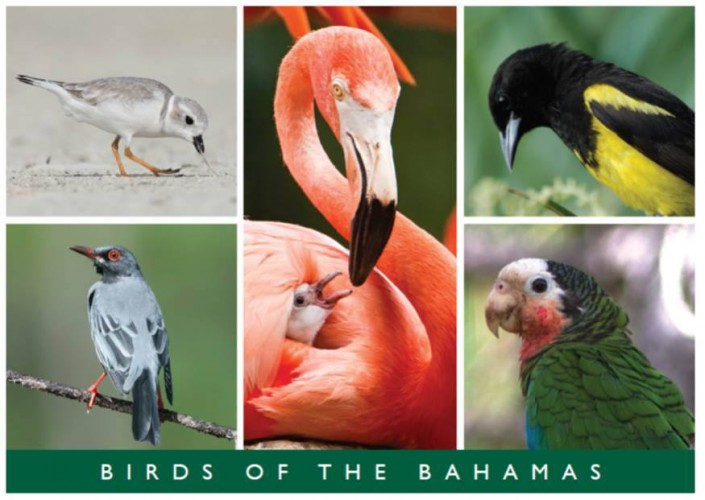

We not only focus on breeding, migration, and wintering of the plovers, but the importance of their habitat to a suite of species. In The Bahamas, the tidal flats used by the Piping Plovers are of huge importance to the ecological value and economy of The Bahamas, as the flats are also used by bonefish, conch, and shark species. We had both classes conduct similar projects — interpretive signs placed on the breeding and wintering grounds — using their writing skills and original artwork. The students also participated in field trips where they learned how to use spotting scopes and binoculars to find and identify shorebirds.

Three years later, we still are teaching our core lessons, but have vastly expanded on the curriculum and projects, as well as extending the program onto another island, Eleuthera, which is just south of Abaco. We now are working with Cherokee Primary in the settlement of Cherokee Sound (Abaco) and Deep Creek Primary (Deep Creek, Eleuthera). We have continued working for the last three years with Amy Roberts Primary School and Ocean City Intermediate School. Back in the United States, we have added a second class from Ocean City, as well as the Leeds Avenue Elementary School Environmental Club (Pleasantville, New Jersey) led by Mary Lenahan. We’ve added new components to the curriculum such as bird anatomy, foraging differences between species of shorebirds, invasive species, habitat assessments (including macroinvertebrates) and marine debris.

We continue to implement interpretive signs as a project with classes that are in their first year of the program, but have come up with new and exciting projects to keep the students (and teachers) motivated and engaged to continue participating as a sister school. For example, during the second year we worked with Amy Roberts, we removed 1,500 Australian pine (Casuarina spp.) from Green Turtle Cay as it degrades the habitat for piping plovers and other species. We created a Piping Plover activity book complete with crossword puzzles, word searches, and mapping activities designed mainly by the students at Ocean City Intermediate School, Leeds Avenue Elementary School, and Amy Roberts Primary School. Because Cherokee Primary and Deep Creek Primary are new to the program this year we hope to have their students create interpretive signs, while the second and third year students in the Program may develop PSA-type videos this year and pen pal letters to their respective sister schools in the United States.

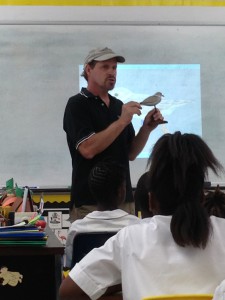

Throughout the year, each class receives one or two classroom lessons and a field trip. We keep busy during the few short weeks we have in The Bahamas; coordinating the field trips, conducting surveys, presentations, and working to continue to build and strengthen our existing relationships with partners, such as Friends of the Environment and local citizen scientists. This year, we’ve reached over 120 students in the program, both from the Bahamas and in the United States.

One of the most rewarding aspects of the Shorebird Sister School Network is that we are able to provide lessons to the some of the same children throughout multiple years in the program, which strengthens the conservation messages we are trying to instill in the upcoming generations. We hope to foster a greater appreciation for wildlife, especially for the Piping Plover and its habitat, and inspire students to help now — and later on in their lives as adults — ensure the recovery and survival of the bird for years to come.

Learn More:

- Conserve Wildlife Foundation’s Online Field Guide: Piping Plover

- Conserve Wildlife Foundation’s Beach Nesting Bird Project

Stephanie Egger is a wildlife biologist for Conserve Wildlife Foundation of New Jersey.