Scarcity and Abundant – Shorebirds Near the Finish Line on the Delaware Bay

By Dr. Larry Niles, LJ Niles Associates, LLC

Our latest catch of red knots and ruddy turnstones two days ago (May 27) suggests 2017 to be one of the most challenging years for our 20 years of work on Delaware Bay. It challenged the birds for certain.

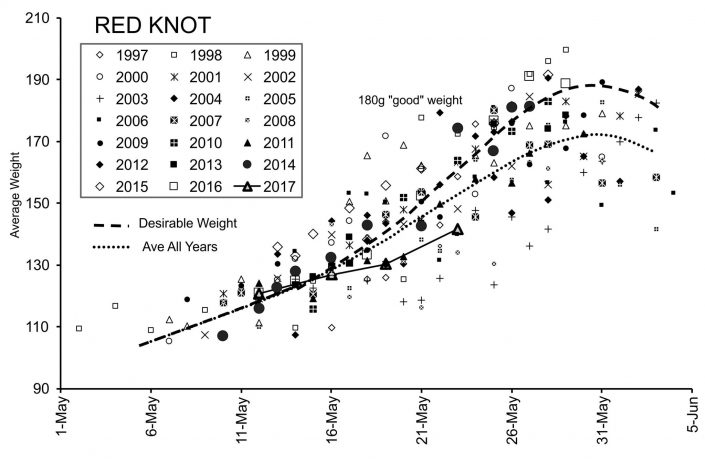

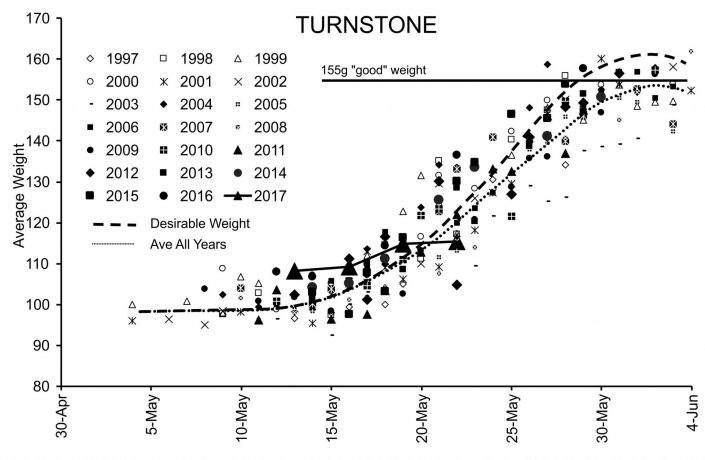

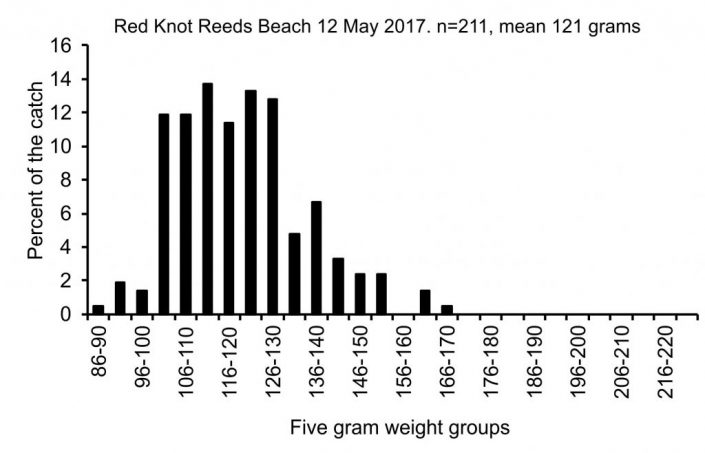

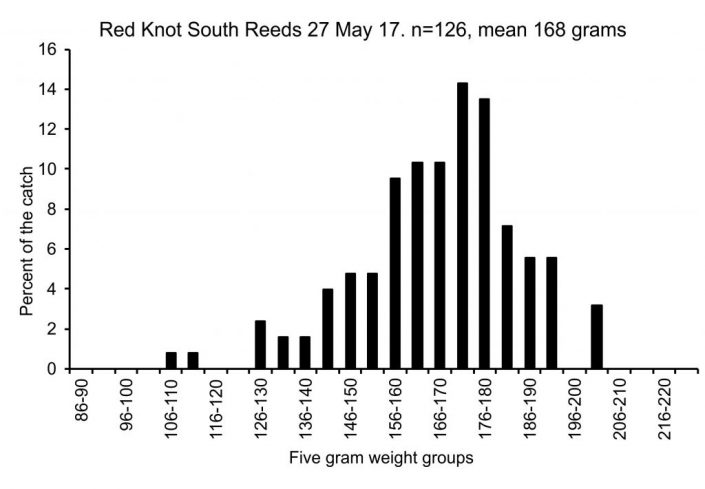

For example, as of two days ago (May 27), the average weights of red knots remain mired in the mid 160’s when it should be in the 180-gram range. This seems a minor difference but to red knots it means a flight through the cold and often inhospitable north country of Canada and dropping out of the sky never to be seen again or landing and never attempting to breed. We really don’t know for sure what happens to ill-prepared shorebirds, except they are less likely to be seen ever again. In 2017 most birds will be ill prepared.

This season also challenged our understanding because it lies so far outside the norm. To be sure the cause of this dramatic scarcity of horseshoe crab eggs springs from the cold weather this May. We started with a good crab spawn in the first week of May, when water temperatures rose somewhat faster than normal, a consequence no doubt of one of the warmest winters on record. Then cold and wet weather dogged the Bayshore until the day of this post. Today, temperatures will rise no higher than 70 degrees Fahrenheit and the prospects for warmer weather are unlikely for the rest of the week. The cold air temperatures forced down the bay temperature in the second week and although it has gradually improved it is still low by normal standards.

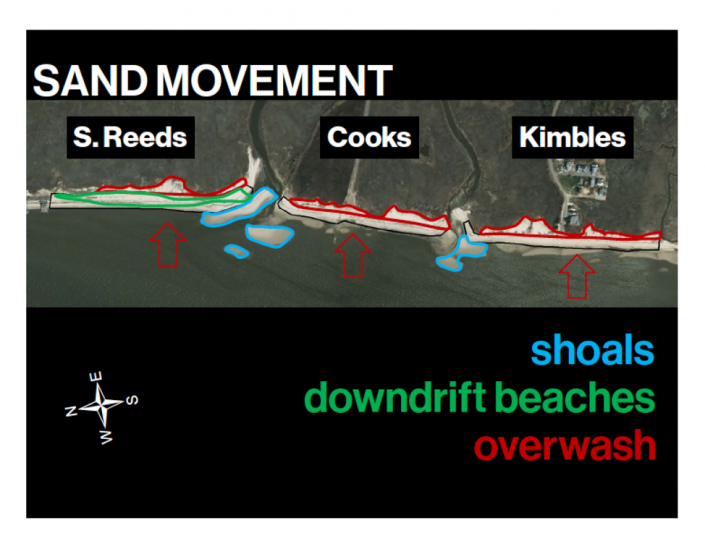

All of this led to generally diminished horseshoe crab eggs especially on the beaches, the mainstay of most stopovers of the past. This year crabs mostly spawned in the creek mouth and outer creeks shoals, mostly spurred to spawn by tidal waters warmed by the movement in and out of the small estuarine systems. Water moves in with the tide and out again to the creek mouths twice a day warming the shoals.

The Importance of Tidal Creek Mouths and Shoals

The creeks also accumulate sand leaving them loose and perfect for crab spawning. Even in good years, egg densities in the creeks top all beaches, no matter where they occur. The sands of the shoals loosen by the waves of the Bay and release more buried eggs than those buried in the beaches, making more available to the birds. The creek mouths on the Cape May peninsula from Green Creek to Moores Creek saved the birds from an even worse fate this year and the best were those that benefited from the restoration of Reeds, Cooks, Kimbles and Pierce Point Beaches. As it happens a major portion of the Bay’s knots stayed in this area throughout the entire month but flying widely in search of pockets of good spawning in other places. This year Norbury’s in the south and Goshen in the north stood out, and extended the core stopover area.

Spawning Starts Again

Then in the last three days all changed. The new moon tides, reaching around 8 feet for four nights in a row, spurred spawning despite the relatively cool water. Today, May 29, the crabs shifted into high gear.

It takes a lot of crabs breeding to bring eggs to the surface on the beaches, there must be enough breeding for one crab to dig up the eggs of another. For the first time, this occurred in the last few night and we finally saw green eggs on the sand. A welcoming sight for the birds, who could barely stand still and gobble up the fat producing eggs. With most of these Arctic nesting shorebirds remaining in the Bay and apparently feeding right into the night, they still might reach the fat gain finish line and only lose a few days reaching the Arctic. The next few days will tell.

Can they though? A good question and just one of the many that have challenged our team’s knowledge of this well-known stopover. With literally centuries of combined experience (many of our team, including this author, are long in the tooth as the Brits would say) we still kept guessing what would happen next throughout the season. Would the birds suffer mighty declines as a consequence of the generally diminished spawn of horseshoe crabs? Or will they build weight in time to get to the Arctic in good condition? This is usually the central question.

Why Are There Fewer Knots?

An equally intriguing question, however, is why have red knot numbers in Delaware Bay declined this year? We estimate shorebird numbers in two ways, direct observation by aerial and ground counts and a statistically derived estimate based on the resighting of birds flagged with unique IDs. Our aerial and ground counts tell us how one year compares to another because we have been doing shorebirds counts by airplane, boat and on the ground since 1981. This year the number fell dramatically.

At the start of our project on Delaware Bay in 1986, we had nearly 100,000 knots on the Bay and nearly 1.5 million shorebirds of all species. The number of knots declined to around 15,000 in the mid-2000’s, then jumped to over 24,000 over the last four years. This year our best estimate is around 17,969, a 5,000-bird decline. Why did this happen?

One must always consider the possibility of a large group of birds dying. But this is not likely.

More likely, some portion of the knot flock came to the Bay, and on finding too few eggs or too much competition, moved on to better places. The ones moving on could have been the short distance migrants, those who spent their winter in Southeast US or the Caribbean. These birds travel a shorter distance and so have a longer time and lower energy needs than those that winter in South America. These long-distance migrants would have a very difficult time gaining weight on anything other than crab eggs (I explained this in a previous post). There are two reasons to believe the short distance birds moved on from the Bay this year.

The first is the discovery of birds banded in Delaware Bay this year and reported elsewhere. I reported on Mark Faherty’s Ebird report of a knot he saw in Cape Cod, that was flagged by the Delaware Bay Shorebird Team on May 16, 2017. The second line of evidence is the 1,300 birds seen by our team feeding on a 10-mile stretch of the Atlantic Coast marsh from Cape May to Stone Harbor. Play this out over the entire coast of New Jersey and other places with sand and marsh, like Cape Cod, and one could easily imagine 5,000 knots using other places.

But this reduction in population also suggests an explanation for the sudden rise in numbers found in 2013. Did the restoration of habitat on the Delaware Bay coast bring back knots that once used the Bay but stopped because of the lack of available eggs? In other words, did the increase in numbers seen in the Bay reflect a return of birds and not a population increase? This year’s loss may simply be a result of those returning birds, leaving once again.

Let’s hope so. At any rate, eggs are now available to all birds in the Bay and we should start seeing them leave for the Arctic. Let’s hope for that too.

Dr. Larry Niles has led efforts to protect red knots and horseshoe crabs for over 30 years.

LEARN MORE

- Delaware Bay Shorebird Project

- 2017 Delaware Bay Shorebird Project blogs

- 2016 Delaware Bay Shorebird Project blogs