The Importance of water temperatures, windstorms and shoals on the Delaware Bay

By Dr. Larry Niles, LJ Niles Associates LLC

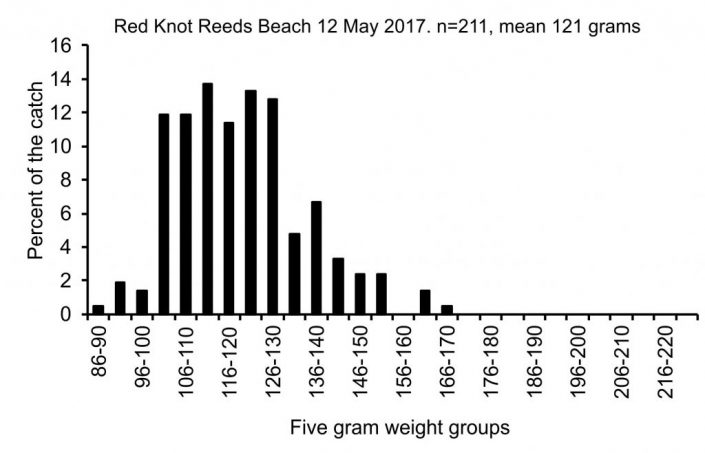

As we begin our field work on Delaware Bay shorebirds, our 21st season, oddly enough we are once again faced with extraordinary circumstances. As usual, the birds, after various flight of up to 6 days of nonstop flying, arrive in emaciated conditions. For example, in one catch this week we caught several red knots at around 86 grams far lower than normal weight of 130 grams. Putting that into perspective, a woman of 145 pounds would tip the scale at 93 pounds while a male of 175 pounds at 113 pounds! In other words, these birds are desperate to feed on the only prey on which they can build weight fast, the eggs of Delaware Bay horseshoe crabs.

But the various impacts of climate change and destructive forces of sea level rise, storm surge and out of normal weather patterns can wreak havoc on the timing of the horseshoe crab spawn. It messes with the heating and cooling of the bay and when combined with the normal variation one expects in an estuarine system, it creates almost unpredictable consequences.

Adding more uncertainty to this mix is the ongoing harvest of crabs for bait and the irresponsible bleeding by international medical companies. Both kill hundreds of thousands of crabs every year while doing nothing to create new crabs. Their combined impact has put the brakes on any recovery of the population after they both nearly mortally wounded the Bay population in the 1990’s and early 2000’s. Higher numbers of crabs would overcome a lot of early season uncertainty; lower numbers exacerbate them.

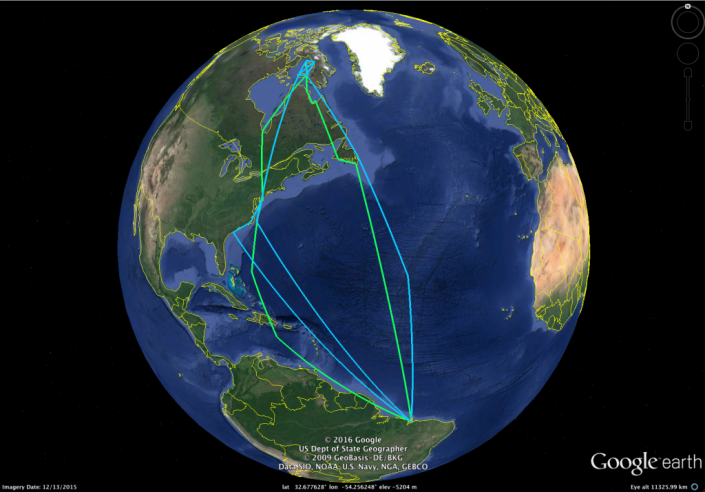

And thus, the story of this early part of the shorebird stopover. It starts with the odd weather this April and May. Can everyone remember how warm the weather of this winter? The map below is a reminder that it was one of the warmest on record. The figure below that shows how the Bay’s water warmed early reaching the threshold temperature for horseshoe crab breeding by early May. We trapped sanderling in the first week and were surprised to see a truly great crab spawn on May 4. Thank God for that.

By the second week of May and yesterday (May 16) temperatures plunged in horseshoe crab world. We generally consider water temperature of near 59 degrees necessary for crabs to spawn in great numbers. We reached 62 degrees on May 4, then it went down to 58 degrees, lingering there for five crucial days.

At the same time, we suffered brutal westerly winds. Wind from this direction gins up waves on Delaware Bay that crash against many of the important crab spawning beaches. Crabs don’t spawn in waves.

And just as the first flush of shorebirds came to the Bay, over 5,000 red knots on the New Jersey side, all the spawning shut down. All tried desperately to find enough horseshoe crab eggs to regain lost weight and begin the process of doubling their body weight.

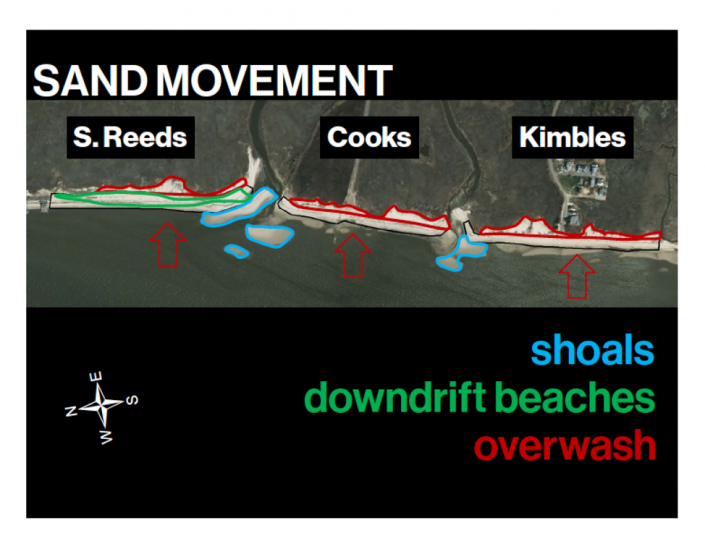

Fortunately, breaking waves and cold water will prevent crabs from spawning on the beaches but not in the intertidal creeks. One of the key features of the New Jersey bayshore are its abundant tidal creeks. Most drain only tidal watersheds, draining and filling marshes twice every day. Naturally they build sand shoals because sand moves around the Bay generally in a south to north direction along the Cape May peninsula. When sand encounters the currents of the creeks, it settles forming shoals.

These shoals support most shorebirds during these early days. This is so because the intertidal flow of water into the marsh and out again warms the water that flows over the shoals. The shoals themselves are practically paradise for breeding crabs because of the loosely consolidated and large grain sand. They breed with abandon laying eggs in the shifting sands that brings many of the eggs to the surface where shorebirds can prey upon them. And they do.

This is what happens in the early days of this season. It was nip and tuck for most of the scientists, not knowing if the shoal resources would hold up to an ever-growing number of shorebirds arriving in desperate condition.

But today (May 19) we enjoyed warmth with the promise of the season back on track.

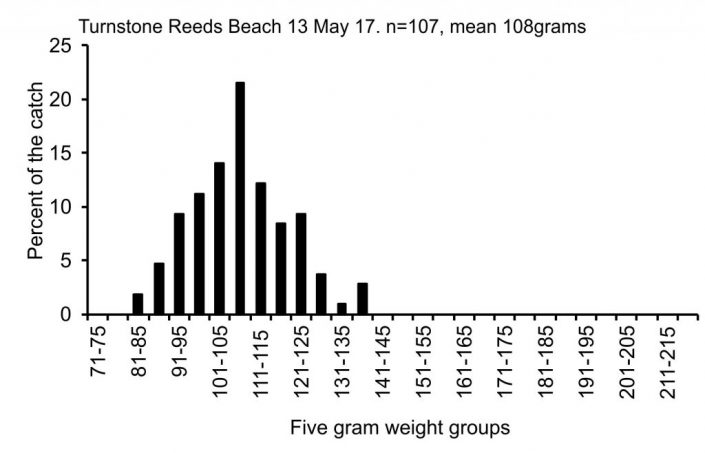

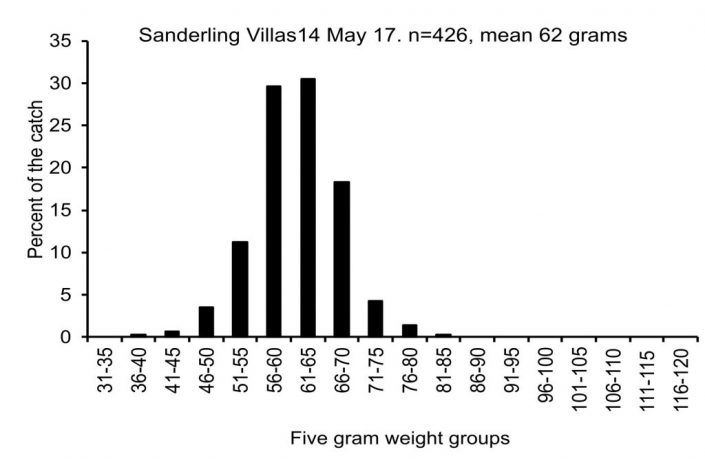

In the last 5 days, we were able capture enough knots, turnstones and sanderlings to track conditions and add new flags to the population for a later determination of population size. Despite adversity, so far so good. The data for each species is below.

Dr. Larry Niles has led efforts to protect red knots and horseshoe crabs for over 30 years.

LEARN MORE

- Delaware Bay Shorebird Project

- 2017 Delaware Bay Shorebird Project blogs

- 2016 Delaware Bay Shorebird Project blogs