Shorebird Expedition Brazil: Conducting a scientific investigation in a tropical wilderness

By Larry Niles, LJ Niles Associates LLC

It’s hard to imagine the difficulties of people living here at Latitude 37 Degrees North when arriving at the equator in northern Brazil. It challenges even the hardiest of biologists. However, after three days our team has not only acclimated but we accomplished surveys in two separate estuaries.

Low tide was cut short on our first day in the field, while high tide persisted longer than we expected which challenged our surveying since it must take place when birds forage. Shorebirds typically forage until 1 to 2 hours before high tide and start again 1 to 2 hours after high tide, usually resting and digesting the food consumed at the lower tides. Because we intend to understand the foraging habitats of shorebirds in the wintering area, we must focus on the lower tides. This is always difficult due to logistical issues such as renting boats, equipment failures, and long distance from the ports present an array of complications. Still, we were able to go out in the field and collect some data.

The next day we did marginally better, each team member faced different problems. Our boat engine failed and we had to paddle back to port, another boat took so long to get to the shoal we intended to survey that it had already been covered by the tide. But this is the nature of field work anywhere.

No matter the complication, it is important to stick to our rigid protocols. Our goal is to determine the best places for shorebirds in this area. We must work with the shorebird’s behavior because each tidal stage creates different value. In a wild place such as this, they will choose to roost as close to the foraging areas as possible. In fact most will just roost then feed as the tide recedes then feed as the tide rises and then roost again. So locating the feeding areas will usually indicate the roosting areas.

But things can go awry. In human dominate habitats like New Jersey, birds find it hard to roost near foraging areas. Most often the high tide forces them into people jogging, dog walking or enjoying flushing shorebirds. So the shorebirds must leave, unnecessarily burning valuable fuel and suffering greater danger from avian predators.

The night-time roost creates the real threat here in Brazil and everywhere. At night many dangers lurk. Ground predators, such as owls, feral cats, raccoons, and even people will take advantage of any unwary or sickened bird. It is worse when birds are forced to use areas that are less secure than others. This can happen naturally at spring tides, for example, when the very highest high tides force them closer to the dangers lurking in the dunes or mangrove forests. In places like Hereford, New Jersey, people often force birds to use more dangerous areas.

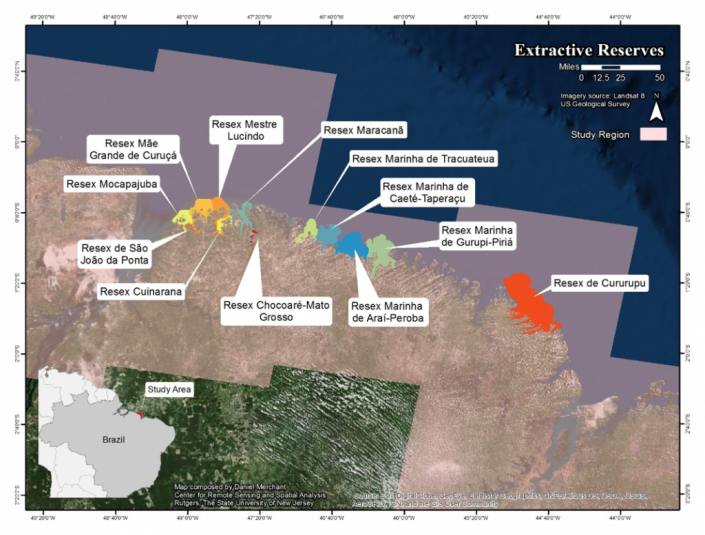

So our goal here is to map all the areas of importance – foraging, day-time roosts and night-time roosts. But we hope to do it with remote sensing; satellite maps that are trained by a mathematical model, that are, in turn, trained by our field data. We count birds, photograph the surrounding habitats, precisely locate the sites, and even look at the substrate. Is it mud, sand, muddy sand, sandy mud and so on?

Doing this in New Jersey is difficult. Doing it in the northern coast of Brazil presents untold challenges. One cannot easily access the coast here. We have to rent boats to take us out to the birds, conduct surveys then get back before dark. Sometimes we go out for days and stay in remote fishing villages, sometimes with only a floor to sleep and no facilities or power. Imagine unrelenting heat, mosquitoes, persistent blowing sand, copious sweat, and trying to conduct a scientific investigation. That would be demanding in any environment.

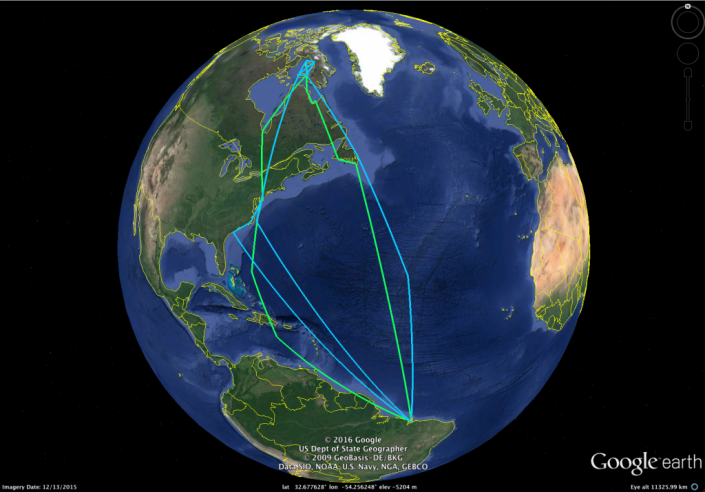

So this is the challenge of our crew – and they do it aplomb! Last year one of the boats sank in 55 feet of water 8 miles out to sea. We all made it to land safely but we lost much of our equipment. The day after was grim, wondering if we should we go on or go home? Without hesitation, not only did the crew go on to complete the survey but we ended up capturing twenty-two geolocators from ruddy turnstones tagged two years earlier. A good crew is hard to put together and stay productive in these conditions. A good spirit is the most important thing.

So we completed two days of surveys at the western end of our 150 miles long study area. Today we prepare for three days out to a remote area, accessible by boat only. As I write, the team prepares for food, water and all the necessities of spending three days with minimum comfort. We hope to camp in a fishing village, maybe a house, but we won’t know until we get there. We must prepare for all possibilities.

Our understanding of the inner workings of the Brazilian Extractavista reserve system grows every day. This system I believe holds great hope for us in the United States because it serves both the wildlife and fish and the people living in the landscape. Pretend, for example, on Delaware Bay, the rural towns and the residents get first crack at the sustainable management of resources, not the companies exploiting them without regard to the future, as it is now. Instead of few people earning a good living off Delaware Bay resources, many would. Rural American would be transformed. This is what ICMBio hopes to achieve in this much poorer area.

Two members of our team are managers of the seven reserves in Para, our study site. They told us, for example, ICMBio (Chico Mendes institute), the federal agency in charge of the extractive reserves, pays a subsidy for local fishermen in exchange for helping manage the fishery resources. But the subsidy is limited to existing residents, not people within new reserves because of the new conservative government. One can see right away the challenges of two people managing seven reserves covering a coastline the size of New Jersey. Budget cuts have taken away all equipment funds. They must even clean their own offices as most nonessential staff has been cut under the new conservative government, a government accused of unfairly deposing the most popular liberal party.

This should resonate in the United States because it could be coming soon to a wildlife reserve near you.

Dr. Larry Niles has led efforts to protect red knots and horseshoe crabs for over 30 years.