Early days on Delaware Bay – Horseshoe Crabs Just Beginning To Breed as Shorebirds Arrive

by Larry Niles

Horseshoe Crabs Just Beginning To Breed as Shorebirds Arrive

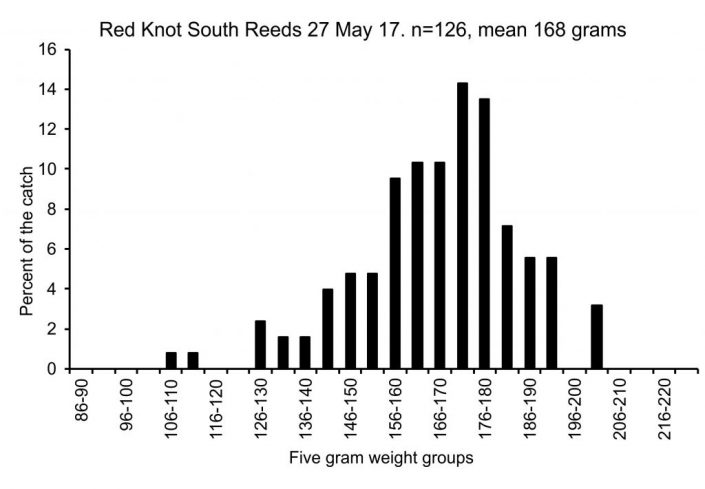

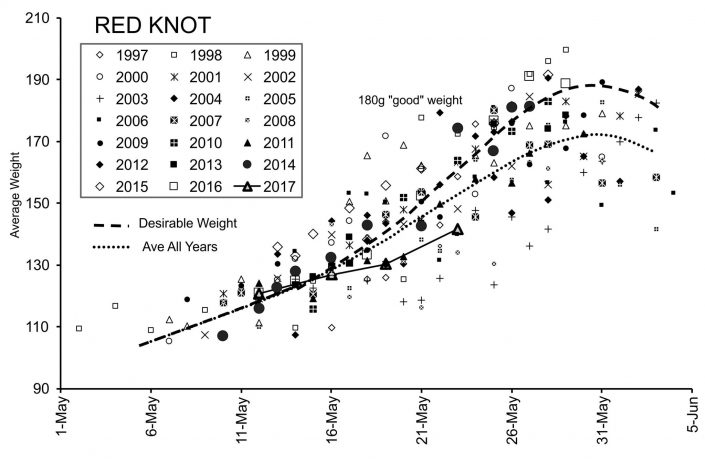

Delaware Bay horseshoe crab eggs reach sufficient levels to give red knots and other shorebirds a good start on the fat they need to fuel the last leg of their yearly journey in the first week of the stopover ( May 12-19). Knots need at least 180 grams to fly to the Arctic and breed successfully. This week we caught birds that weighed 93 grams which is 30 grams below fat-free weight. These birds had just arrived from a long flight, probably from Tierra del Fuego, Chile or Maranhão, Brazil. In the same catch, we weighed red knots as high as 176 grams or only 5 grams from the 180-gram threshold. These birds are probably from Florida or the Caribbean wintering areas and so arrive earlier, resulting in them having more time to gain weight. All together it looks like a normal early migration and a modest horseshoe crab spawn, just barely enough for the birds in the bay.

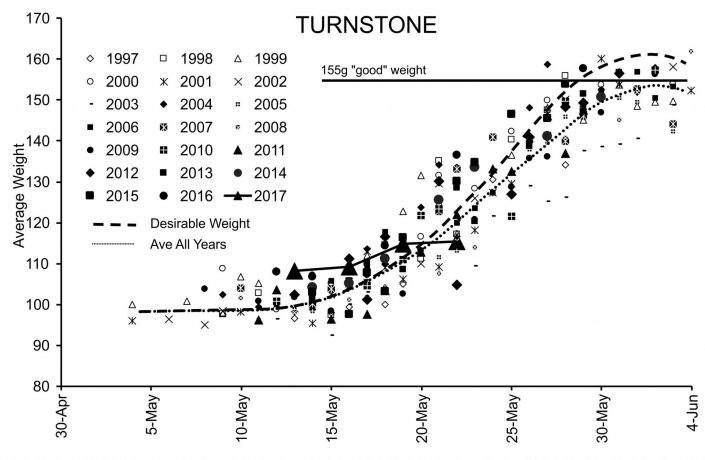

However, we are still short of about half the population. Our bay wide count won’t take place until next week on May 22 and 26. At this point it looks like we have about 14,000 knots in the bay, of which 8,000 are in New Jersey. In the last 5 years we have had a bay wide population of about 24,000 red knots. The situation is similar for ruddy turnstones and sanderlings. The southernly winds of the next few days will almost certainly bring in the rest of the flock by mid-week.

The Stopover Habitat is Growing

The condition of the stopover is mixed.

The work of Niles & Smith Conservation Services, Conserve Wildlife Foundation of NJ, and American Littoral Society continues to supply high-quality habitat for horseshoe crabs. We have developed an efficient system for maintaining the essential requirements of a good spawning beach, deep and large grain sand with berm heights that prevent over washing in a way that keeps cost down. First, by creating low oyster reefs to break waves in lower tides, thus protecting beaches from wind waves at low and mid tides. Second, by placing sand on beaches that typically erode fast losing sands to adjacent creek inlets and the next beach south. This way we can use one restoration to restore three different places. For example, Cooks Beach loses sand to South Reeds.

Oddly these successes may be contributing to the next big problem for the birds. The state of Delaware has been carrying out much larger scale beach replenishment projects that have added significant new sandy beach for crabs spawning. At the same time the Atlantic States Marine Fish Commission has failed to deliver on its promise to increase the number of crabs. The population is still 1/3 below carrying capacity or the number that existed 20 years ago. The same number of crab divided by more beach equals decreasing crab densities. Decreasing densities means fewer eggs reaching the surface because crabs are not digging up existing eggs to lay their own.

In other words, we need more crabs.

The Industry Finds New Ways around the ARM Quota

But the resource agencies seem perfectly happy to keep killing adult crabs for both bait and bleeding at near historically high numbers. Bait harvests recorded as coming from the bay have stayed the same, however other states such as NY are still taking and landing large numbers of crabs despite having no known crab historic population of their own. Additionally, Virginia states that a crab population still exists in the state, even though most field biologists consider them lost. The truth is they are very likely taking Delaware Bay crabs and landing them as their own.

The Conservation groups are no longer satisfied with this loose regulation and are calling for regulations similar to those used for Striped Bass. The Delaware Bay harvest should be restricted to just the quota agreed upon by everyone through the Adaptive Resource Management system. All other landed crabs should be genetically linked to a source population, and if they do in fact come from Delaware Bay they should be taken out of the ARM quota. No one should be allowed to get away with killing our crabs outside the quota.

Or just stop the senseless killing of these valuable animals as bait for the dying couch fishery.

The same goes for the killing of crabs by the companies bleeding crabs. The industry makes untold millions (the numbers are hidden from the public) but does virtually nothing to conserve the crabs while killing thousands. Their own estimate is well over 65,000 a year, but independent estimates double that. This killing could also stop because a new synthetic lysate is available and can be used now, potentially cutting the need for natural lysate by 90%.

An Ecosystem Collapse and the Need for More Crabs

Why kill such a valuable animal? It all started because the fishing industries saw little value and figured why not destroy the population until they are no longer economically viable. Its called economic extinction and sadly it’s a tradition amongst Delaware Bay fishers still carried out this to this day on eels, conch, and other species. But they didn’t know back in the early 90’s they would wrecking the entire ecosystem.

In 1991, we counted an average of 80,000 horseshoe crabs/meter squared. Now we count 8,000. Then the eggs stayed at that level for all of May and June then hatched young at similar densities. In other words, the horseshoe crab was a keystone producer of an abundant resource that maintained the bay ecosystem. It was not just chance that at the same time the bay has one of the most productive weakfish and blue claw crab fisheries in the Atlantic coast. Fish populations blossomed with the flush of horseshoe crab eggs and hatched young each year.

Now we must bring it back. For the birds, for the fish, and for the people who love to bird and fish.

We are grateful to the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and other donors who make this project possible.

Dr. Larry Niles has led efforts to protect red knots and horseshoe crabs for over 30 years.