International Migratory Bird Day Series: Piping Plover

CWF is Celebrating International Migratory Bird Day all Week Long

by Lindsay McNamara, Communications Manager

CWF’s blog on the piping plover is the second in a series of five to be posted this week in celebration of International Migratory Bird Day (IMBD). IMBD 2016 is Saturday, May 14. This #birdyear, we are honoring 100 years of the Migratory Bird Treaty. This landmark treat has protected nearly all migratory bird species in the U.S. and Canada for the last century.

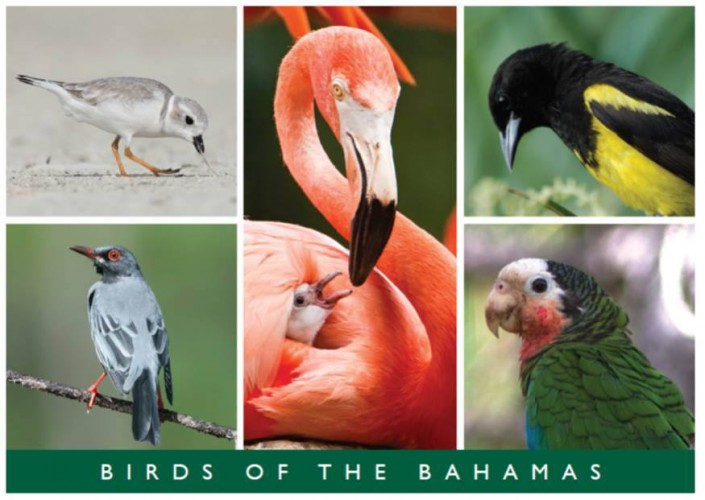

The piping plover – a small sand-colored shorebird that nests in New Jersey as part of its Atlantic Coast range from North Carolina up to Eastern Canada –weighs only one to two ounces and is about six to six and a half inches long. These tiny shorebirds migrate all the way to their wintering grounds along the coast of eastern Mexico and on Caribbean islands from Barbados to Cuba and the Bahamas.

Migrants can be seen in New Jersey from early March to late April and again from mid-July to the end of October. Females are the first to leave the breeding grounds, followed by males, then juveniles. Breeding plover “hot spots” in each coastal county of New Jersey are Gateway National Recreation Area – Sandy Hook Unit, Barnegat Light, North Brigantine Natural Area and Stone Harbor Point.

We see a number of migratory piping plovers in New Jersey because the Garden State is roughly in the middle of their breeding range. Todd Pover, CWF’s beach nesting bird project manager, reasons that we have a high number of Eastern/Atlantic Coast Canadian breeders that stop in New Jersey — based on band resights — albeit usually for just a day on their way north to breeding grounds. Therefore, New Jersey may play an important role in the piping plover life cycle not just for breeding, but for migration as well, which emphasizes the importance of protecting shorebirds in all phase of their lives or “full life-cycle conservation”.

Piping plovers face a number of threats, including intensive human recreational activity on beaches where they nest, high density of predators, and a shortage of highly suitable habitat due to development of barrier islands and extreme habitat alteration. Sea level rise and increased storm activity related to climate change will also likely lead to more flooding of nests.

Federally listed as a threatened species in 1986, piping plovers have since recovered in some areas of the breeding range. Yet piping plovers continue to struggle in New Jersey, where they are listed by the state as endangered. For more information about piping plover nesting results in New Jersey, please read Conserve Wildlife Foundation’s 2015 report.

CWF, in close coordination with NJDFW’s Endangered and Nongame Species Program, oversees piping plover conservation throughout New Jersey. Staff and volunteers help erect fence and signage to protect nesting sites, monitor breeding pairs frequently throughout the entire nesting season from March to August, and work with public and municipalities to educate them on ways to minimize impacts. Although conservation efforts on the breeding ground remain the primary focus, in recent years, CWF has also begun to work with partners all along the flyway, in particular on the winter grounds in the Bahamas, to better protect the at-risk species during its entire life-cycle.

We are working hard to link students across the piping plover’s flyway through our Shorebird Sister School Network, where we pair up schools in New Jersey and the Bahamas, one of the most important wintering areas for Atlantic Coast piping plovers. Now, we are hopefully recruiting some Canadian students as well.

Conserve Wildlife Foundation will continue to find innovative ways to save the small migratory shorebird. In 2015, 108 pairs of piping plovers nested in New Jersey, a 17% increase from 2014. What will 2016 bring? Follow us on social media to learn more about the tireless efforts of a team of passionate, dedicated biologists working to save the iconic coastal species.

Learn More:

- Piping Plover Nesting Results in New Jersey: 2015

- Conserve Wildlife Foundation’s Species Spotlight: Piping Plover

- Conserve Wildlife Foundation’s Online Field Guide: Piping Plover

Lindsay McNamara is the Communications Manager for Conserve Wildlife Foundation of New Jersey.