A Shorebird’s Paradise

One in a Series of Updates on the 20th Year of the Delaware Bay Shorebird Project

by Dr. Larry Niles, LJ Niles Associates LLC

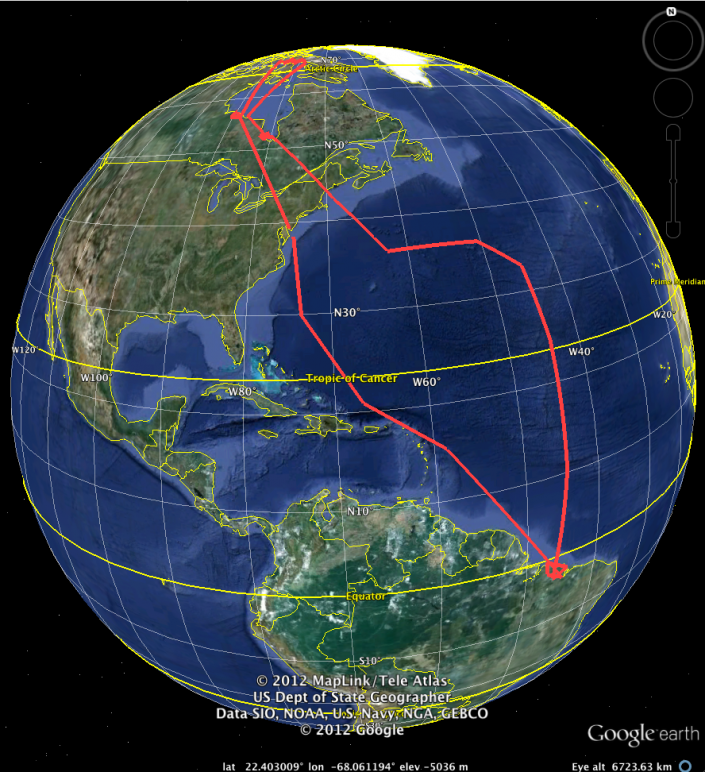

We conducted our first bay-wide count of shorebirds on Delaware Bay and the results suggest we are rapidly approaching the peak number of shorebirds. Last year, we counted 24,700 knots and 16,000 ruddy turnstones. This year’s counts are lower because it’s earlier, but we are still over 20,000 knots and 16,000 turnstones, and 10,000 sanderlings that have stopped over in the bay. These promising results are preliminary, but it seems we are getting close to our peak population of red knots and at the peak of the other two species – if populations are similar to last year.

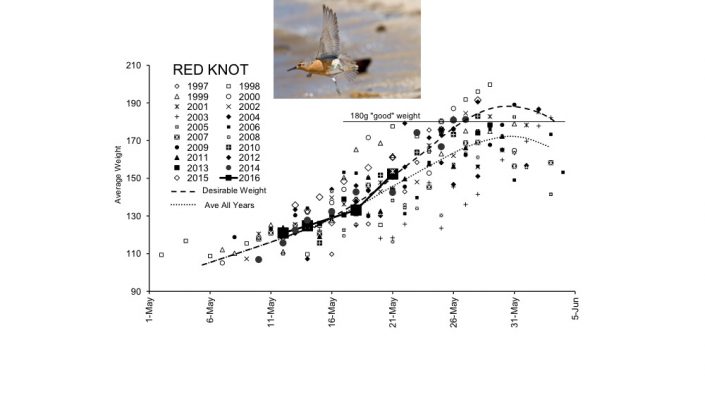

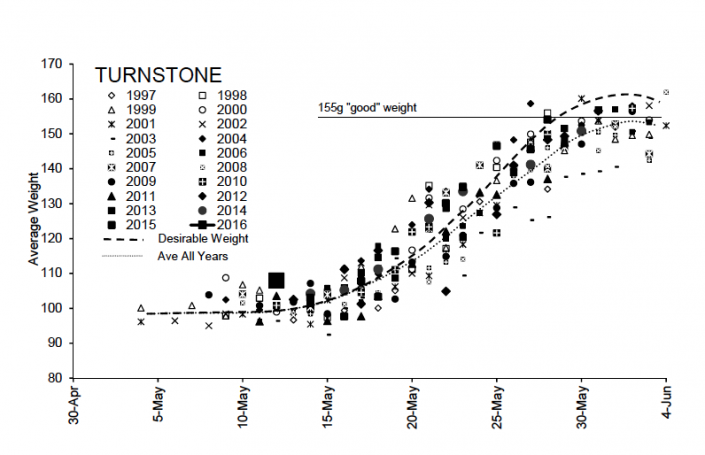

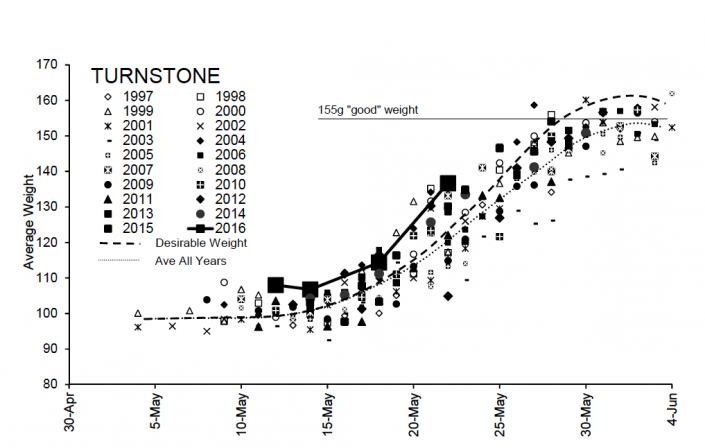

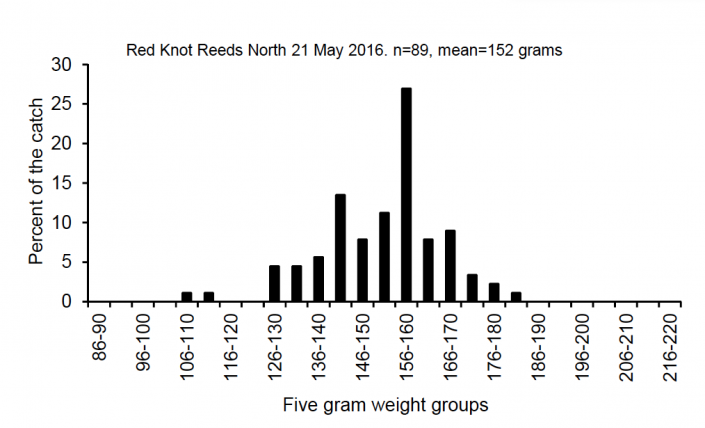

Bird condition also looks promising. Our catches show average weight increases for red knot compared to past years, which is good news given the very spotty horseshoe crab spawn. Ruddy turnstone average weights have increased considerably, the best in the twenty years we have been trapping (see the graph below). The distribution of these weights reveal more.

If we sample the same bird population with our cannon net catches, one would expect increasing average weights but similar distribution of weights – the same proportion of different weight birds, all getting higher. If a new group of birds arrives in the area, then one would see a new distribution of weights, only lower than the group that has been in the area longer. This can be seen in the historgram for ruddy turnstones below. The historgram supports our assumption that a new group of turnstones has arrived in the bay and are busy gaining weight. Based on our last catch, the distribution of knot weights shows no new arrivals, however the aerial survey and ground counts done after the catch point to a new group yet to be sampled. To our team of biologists this data is food for hungry minds. Within a few days, all will be revealed.

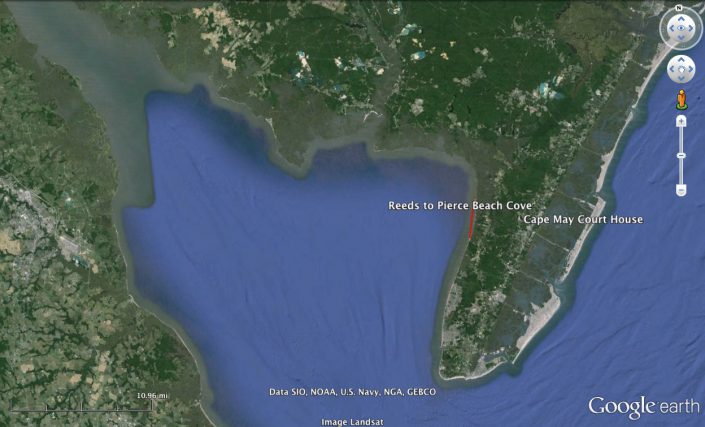

The actual distribution of the birds in the count tells another important story – the importance of the beaches and creeks between Reeds Beach and Pierce’s Point. This 3-mile section of Delaware Bay accounted for more than half of the entire population of red knots on the bay and outsized portions of the other species. This has been consistent through this season and over the last three years – ever since Conserve Wildlife Foundation (CWF) and American Littoral Society (ALS) restored the four beaches with new sand.

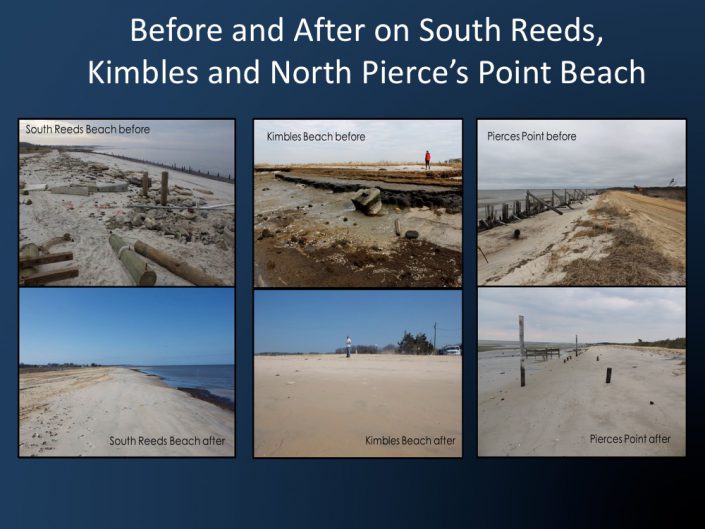

The restoration of these beaches avoided a potential disaster caused by Hurricane Sandy, which not only destroyed seventy percent of all the suitable horseshoe crab habitat on the New Jersey side of Delaware Bay, but it did much more. South Reeds Beach tells the story.

After the hurricane ripped through the area and pounded Reeds Beach with punishing westerly winds, most of the sand had been pushed off the beach and onto the marsh behind it. This unveiled a long standing and nearly impervious layer of rubble, remnants of long abandoned houses, bulkheads and the access road connecting them. We had no idea this laid beneath the sand of Reeds Beach South, but it explained why it never had good crab egg densities. Crabs couldn’t burrow deep enough to lay eggs.

The CWF and ALS restoration teams with funding from the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF), the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation and Community Foundation of New Jersey, along with other groups, removed the rubble and laid down a beautiful sandy beach. Every year since, horseshoe crab egg densities were among the highest in the bay. This, of course, attracted higher than average shorebird numbers which greedily consumed the newly available trove of eggs. Similar work was done at Cooks, Kimbles and Pierce’s beaches.

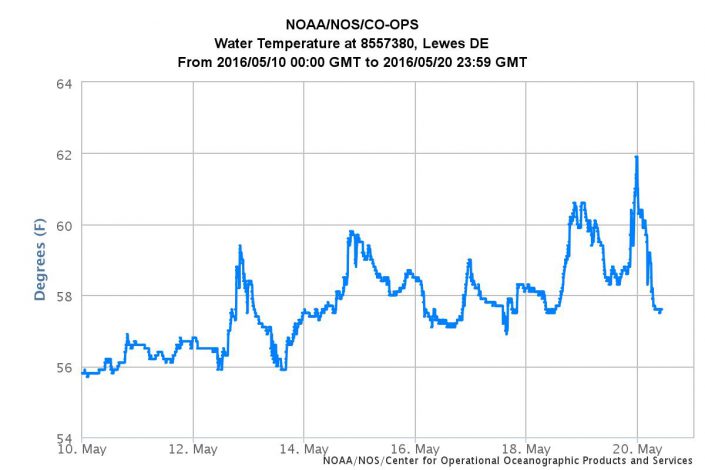

However, the restoration work did even more. Sand naturally erodes from these beaches just as it does on the Atlantic Coast beaches. The sand lost at Stone Harbor and Avalon beaches, for example, ends up in Hereford Inlet. The same happens on Delaware Bay beaches and the eroding sand flows into the the nearby creeks forming beautiful crab spawning shoals. I described their importance in the Reeds – Pierce’s Cove in the previous blog. These creek shoals represent the best habitat in the bay, because they are loose sand, create small inner protected areas loved by spawning crabs and are washed by warm water flowing out from the small intertidal water drainages. Early season spawning almost always occurs in or near creek mouth shoals. Thus, even sand lost from restored Delaware Bay beaches goes to a good end.

One more characteristic, perhaps the most important feature, is that all these beaches, creeks and their shoals together create a small and very important landscape within the overall Delaware Bay landscape. The overall warming creates the best early season habitat for crabs and shorebirds and the continued volume of spawning maintains the value throughout the season. We now have over 10,000 knots on these beaches and thousands of other shorebirds.

All of these important natural features are greatly strengthened by the New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife’s restrictions that keep people from disturbing the birds. Without them, visitors, even those with good intentions, may disturb the birds from feeding. The restrictions are implemented without conflict by a very cheery and passionate group of volunteer stewards who explain the importance of letting the birds take advantage of good habitat. Ironically, the Reeds to Pierce Cove still attracts the most people in the bay because they can easily see the birds from access areas provided at each of five road ends and the Bidwells Creek jetty.

All in all, it’s a shorebird’s – and shorebird lover’s – paradise. But soon it may be a paradise lost.

This year, state and federal agencies permitted thousands of structural aquaculture racks to sprawl over this wonderful shorebird habitat. If all goes according to their plan, soon ATV’s will be rolling all over the intertidal area, disregarding their long-term impact. Welded rebar racks will stop some a portion of the crabs from reaching the beaches, and more importantly impair their return. More and more crabs will fail to breed or die as gulls tear apart crabs stranded on the intertidal shore. Like much of New Jersey, this beautiful cove has the potential to be degraded by runaway commercial exploitation.

There are ways to expand aquaculture without destroying shorebird habitat. This is not one.

Dr. Larry Niles has led efforts to protect red knots and horseshoe crabs for over 30 years.