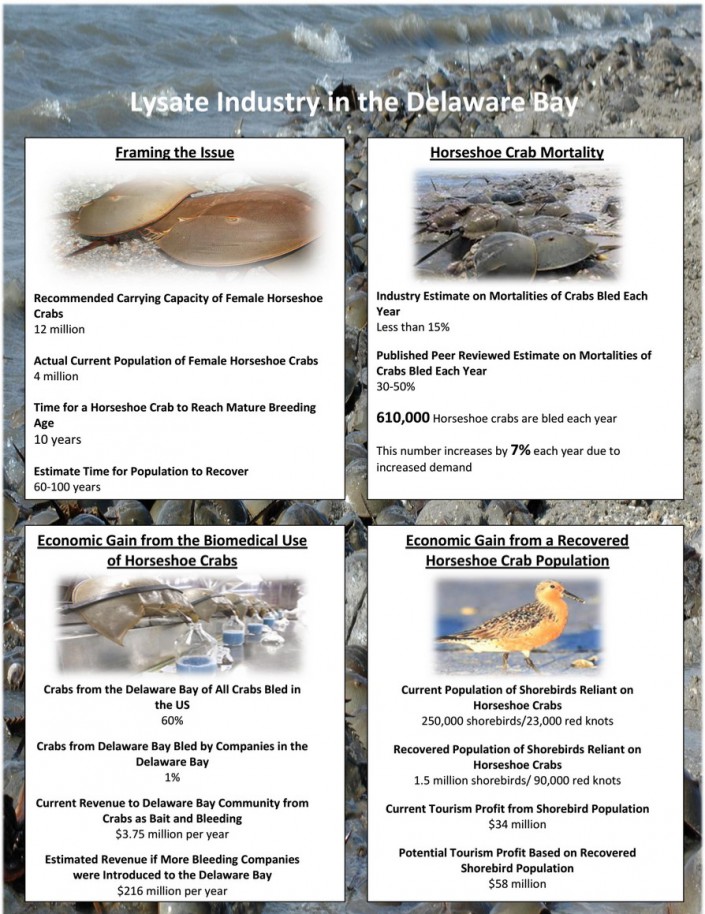

19,077 Red Knots Counted – The Most Seen in New Jersey in a Decade

An Update on the 2015 Delaware Bay Shorebird Project

By: Dr. Larry Niles, LJ Niles Associates LLC

Despite the threatening forecast of a cold drizzle and strong winds, our team persevered to complete the first bay-wide count of this season. On the New Jersey side of Delaware Bay, we counted 19,077 red knots – the most seen in the state in a decade. With Delaware’s shorebird team recording 2,000 knots along their entire shoreline, the total knot count of 21,077 is not far from the 24,000 seasonal maximum of the last three years.

This is good news in either of two completely different ways. One explanation is that perhaps most of the knots have already come to the bay. If so, they are in good time to make weight and are getting close to an on-time departure for the Arctic. The alternative is that even more will arrive and we will exceed our counts of the recent past. Good weights promise good Arctic production; more knots offer new hope.

The numbers of ruddy turnstones (12,295) and semipalmated sandpipers (56,788) are also close to the seasonal maxima counts of the recent past, so they too may soon brave the long flight to their Arctic homes. Our cannon-net catches of turnstones, sanderlings and knots point to weights building quickly.

The weather conditions play with our expectations. For the last few days, high westerly winds have generated beach-pounding waves all along the Cape shore. Its north/south orientation is perfectly perpendicular to the strong winds, and the wind-generated waves shut down horseshoe crab spawning. This forces the birds to seek shelter and better egg densities elsewhere.

Right from the start, the disappearance of the shorebirds we had been seeing intrigued us, for a good wildlife mystery gets consumed in this team like a good bottle of beer. Within hours, Mark Peck and Gwen Binsfeld found the knots south of where we would have expected. The knots, turnstones, sanderlings, and semipalmateds were comfortably riding out the wind storm on the vast, sandy intertidal flats in front of Sunray Beach and Villas. We haven’t seen birds gathering in numbers here since the early 2000’s.

But back to the count. We found shorebirds all along the Bayshore with three areas of concentration. The first was the aforementioned Villas flats. The second was in the Pierces Point to Reeds Beach area, with most in the more southerly portion of the sector. “Not-knots” (mostly semipalmated sandpipers) were seen there in big numbers during the boat survey by Yann Rochpault, Christophe Buidin and Tom Baxter. They saw 12,000 shorebirds along this mostly unpopulated shoreline.

But the real shorebird wonderland of the bay continues to be Egg Island. Few people see this this vast intertidal marsh, and fewer still appreciate its wonder. Egg Island – actually a peninsula – juts miles out into the bay, nearly to the shipping channel. The marsh cradles one of the most diverse bird faunas of the mid-Atlantic. All along its mucky eastern flank, short-billed dowitchers, dunlin, semipalmated sandpipers, black-bellied plovers, and semipalmated plovers comb the eroded banks for crab eggs drifting in the water column from better crab breeding sites. The crabs themselves attempt to breed in the overhanging edges of the spartina marsh, a lost cause; however, because the muck lacks oxygen and the eggs cannot develop. This is bad for crabs but good for shorebirds because most of the eggs end up on the sod banks, easy prey for shorebirds.

But this week, the wonders of Egg Island overwhelmed us. Our team – Humphrey Sitters, Phillipa Sitters and this blog’s author – wove along the shallow shoreline in our intrepid 17-ft Carolina skiff, counting thousands of shorebirds – 8,226 knots, 4,125 ruddy turnstones, 3,000 sanderlings, and 21,000 semipalmated sandpipers. The flocks swirled around the peninsula’s sandy western shore, alighting, then flying, and then alighting again. It was a shorebird dance that was a wonderful sight for increasingly tired-out shorebird scientists.

Learn more:

- Delaware Bay Restoration – RestoreNJBayshore.org

- Conserve Wildlife Foundation’s Delaware Bay Shorebird Project

Dr. Larry Niles has led efforts to protect red knots and horseshoe crabs for over 30 years.