Shorebird Expedition Brazil: Going to the heart of the mangroves

Hundreds of red knots found to cap long day’s journey

By Larry Niles, LJ Niles Associates LLC

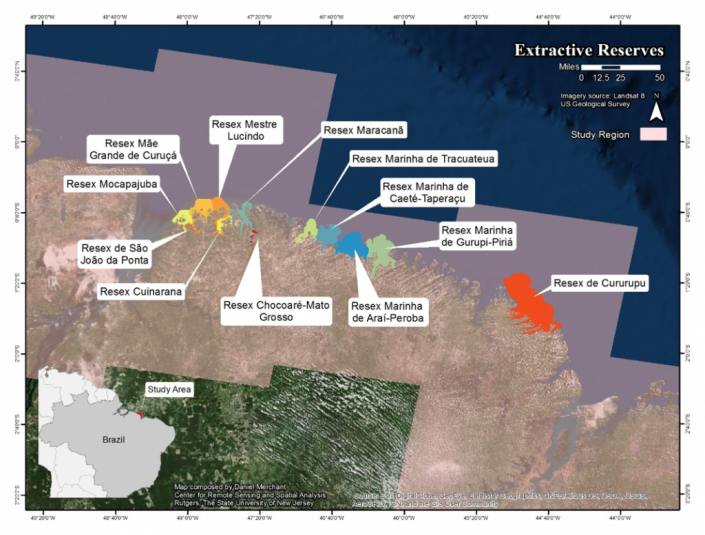

It took us long into the night to reach our next port. We went from the relatively populated area of Braganza to the dark heart of this coastal region of Viseu. In three trucks, we caravanned through a maze of remnant tropical rainforests, cattle pastures, and impenetrable second-growth woodlands. Along the rain-slicked, red clay road, small and desperate looking towns popped out of nowhere always looking like the past was a better day. The road cut through countless mangrove forests that define this region. We reached Viseu too late to do anything but find a place to stay the night.

By noon the next day, we boarded a Lancha boat named Garota Viseu (Viseu Girl). Local shipwrights craft these two-decker boats of about 50 feet in length, primarily to carry cargo and people from port to port. Today it will carry us into one of the most remote estuaries in the 250-mile coastline of this enormous mangrove and beach landscape. Our captain, 78-year-old Benedicto, with one crew navigated the coffee- colored Gurupi, a long river that cuts deep into the tropical coastline.

Bene took his craft down the Gurupi within sight of the wind-tossed Atlantic Ocean. The trade winds blow constantly here, almost always at near gale levels. But then he turned into a small channel directly into the steamy mangrove forest. At first the path was wide, lined with a dense tangle of mangrove on either side. Whimbrels, scarlet ibis, semi-palmated sandpipers clung to tangles of roots as the high tide flooded the soft mud.

Then he took the boat in a channel so narrow, the crew had to duck the whipsaw of mangrove branches. We slowly snaked our way through a tunnel of green until we reached another wide channel. Within a few minutes, we entered another narrow channel ultimately reaching the next bay. Here we felt the full force of the stiff winds and deep rolling swell of the Atlantic. An hour later we weighed anchor at the small community of Apiu Salvadore.

Few people from the outside world come to this community of about 50 ramshackle huts and cabins and about 150 people. As the boat neared the shore with most of the team standing on the roof of the boat, scattered groups of the town’s people stood on the sandy bluffs overlooking the harbor as though we just landed from space. Ultimately, we found them welcoming but wary. Little good comes from the outside to these communities.

Over the next two days, we plied our craft of field biology. We needed to find small boats to take teams to the various shorebird habitats previously determined on our maps. Local craftsmen build these boats. Running about 20 feet in length, they use 10 to 20 horse power engines meant for something like a lawn tractor. Instead of driving a blade, the craftsmen power a long shaft that ends in a 8-inch propeller. The skipper can lift the engine and propeller according to the water’s depth. They suited our needs perfectly.

We fielded five teams in three in boats while Mandy, David Santos, Carmem and I surveyed Lombo Branco Island, about two miles from the Apiu Salvador. The sea shapes this island into a crescent, the inside protected from the restless waves. Nestled within, one could see in miniature, the whole ecological system that creates resources for shorebirds.

At the heart of the island grows a small and stunted mangrove forest and an apicum, or wetland that only floods during lunar tides or spring tides. These are the highest of the monthly cycle of tides but only occur on the full and new moon. Every day the tide moves in and out of this small system. Twice a month the tide floods the apicum for several days at a time.

We arrived on the day of a waxing moon, near full. The very high-high tides reached well within the small drainage flooding habitats that have not been flooded in a few weeks. Shorebirds carpeted the wet mud, searching for all the invertebrate life that flourishes in this habitat. But the productivity only starts there. Here the tidal flow is gentle because the island shields it from the wind tossed Atlantic from all sides except the leeward quarter of the island. This gentle tidal flow flushes sediments from the mangrove swamp, the nutrients of the apicum and the normal productivity of a sediment-rich sandy substrate, forming the base layer of a productive food chain that nurtures small clams and other invertebrate – all prey for shorebirds.

We found whimbrels, semi-palmated sandpipers, ruddy turnstones, short-billed dowitchers, black belly plovers, willets, semi-palmated plovers, sanderlings and collared plovers. In the lower reaches, we found 337 knots, a glorious find that will help our mapping model enormously.

The following day we surveyed a second island, Coroa Criminosa. Why the sinister name we cannot say, but it supported a very similar esturary giving us another successful day. When the tide went out the small island of about 6 kilometers grew to over 20 kilometers. Intertidal sand flats spread out of sight in nearly all directions.

We left the island that night and arrived in Viseu just before dark. Once again we suffered the sway of the Atlantic. After weaving our way back through the mangrove and up the Gurupi River, we landed too late to go on. We were thankful for the modest rooms with showers, a good meal and beer!

Dr. Larry Niles has led efforts to protect red knots and horseshoe crabs for over 30 years.