Using Wildlife Telemetry to Track American Oystercatchers on the Delaware Bay

by Emmy Casper, Wildlife Biologist

Wildlife telemetry is a growing technological tool that uses tracking devices to help answer questions about animal movement patterns. For highly mobile and migratory species like shorebirds, telemetry is especially useful because it offers an opportunity to model migration routes, identify important staging or foraging sites, and learn about bird behavior. Since beginning a comprehensive American oystercatcher monitoring and banding program on the Delaware Bay in 2022, CWF and our partners have set out to learn as much as we can how oystercatchers move around the Bayshore and beyond so that we can apply this knowledge to management decisions. By banding oystercatcher adults and chicks over the last two seasons, we have been able to gain a basic understanding of oystercatcher movements around the Bayshore as well as some of their staging and wintering locations. However, there is only so much we can learn through band resights alone. For that reason, we were very excited to partner with The Wetlands Institute (TWI), Cape May Point Science Center (CMPSC), and Cellular Tracking Technologies (CTT) this past season to pioneer telemetry research for oystercatchers on the Bay.

Step 1: Choosing a Telemetry Method

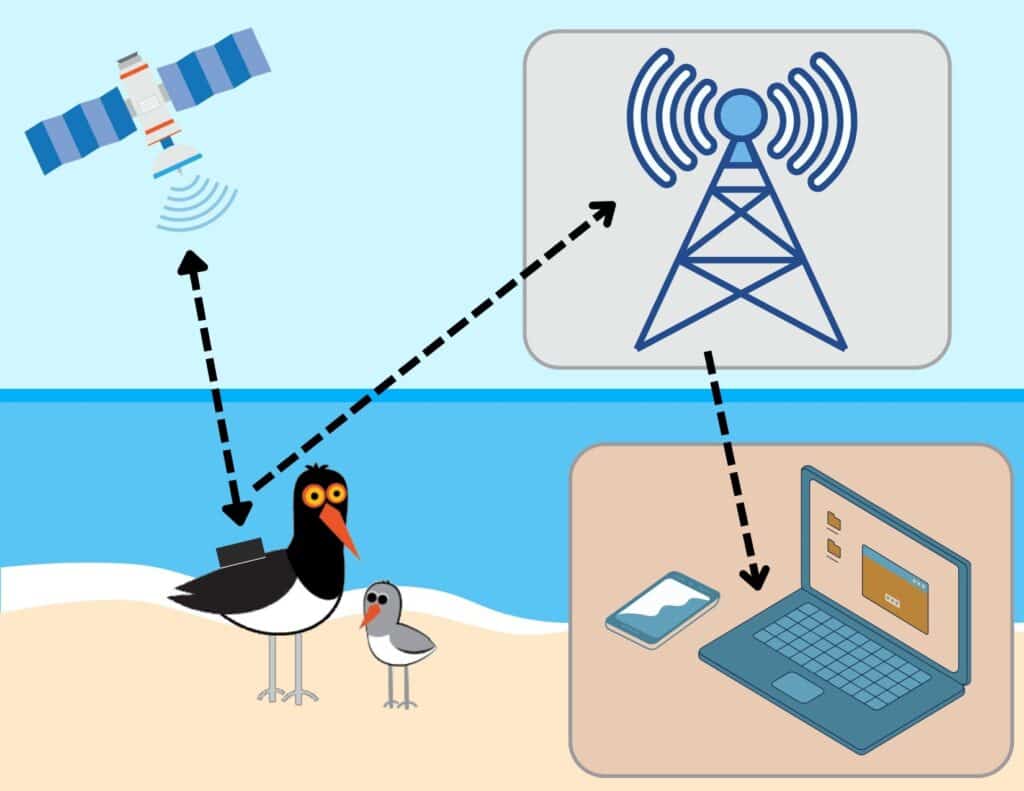

Generally, wildlife telemetry can be divided into two camps: radio and GPS. Radio-tags work by emitting radio frequencies that are detected by radio towers or hand-held receiver devices when the tagged animal is within the detection range. Each transmitter emits a unique signal which allows the biologists to identify individuals. One big limitation of radio telemetry is that tags will only ping when in range of a radio tower (e.g., Motus towers) or handheld receiver, which means it relies on a widespread network of radio towers and/or biologists collecting data in the field. GPS telemetry, on the other hand, works by using satellite signals to pinpoint an individual’s exact location in real-time, similar to the way your cell phone locates your location on a navigation app. The units can store location data and then transfer information wirelessly through cellular networks right to an online portal on a phone or computer. Since this type of tracking does not require local radio towers, it can collect location data anywhere and at any time, which allows biologists to track both fine-scale and large-scale movement patterns. However, GPS transmitters are typically much heavier and more expensive than their radio-tag counterparts, which means this type of telemetry is limited by focal species and budget. While both methods have their advantages, we consulted with CTT to choose GPS units for our oystercatchers, and CMPSC generously provided the funding to purchase five transmitters for the Delaware Bay Oystercatcher project.

Step 2: Deploying the Transmitters

Once we chose the transmitter type, we had to design an attachment method. To our knowledge this is the first time GPS units have been deployed on oystercatchers in New Jersey, so we relied on the expertise of our colleagues working with oystercatchers in other states as well as CTT’s experts. In the end, we decided to use a “leg-loop harness” design based on recommendations from the American Oystercatcher Working Group. This method involves equipping the bird with a custom harness that fits close to its body, around its legs. The transmitter unit rests on the bird’s back so that the solar panels that power the battery are exposed to the sun. Fitting the harness is very precise work, and extra care is taken to make sure the harness is balanced and appropriately snug. Once deployed, the harness remains attached to the bird for the remainder of its life, although every effort is made to recapture the birds and remove transmitters that no longer function.

Oystercatchers are relatively large shorebirds, but we were not prepared for how challenging it was to find heavy birds on the Delaware Bay!

As you may expect, transmitter weight is a limiting factor when it comes to deploying units on lightweight animals like birds. The last thing we want to do is negatively impact the bird’s health and ability to fly. To prevent negative impacts to the birds, the combined weight of the harness and transmitter must not exceed 3% of the oystercatcher’s body weight. Since our set-ups were on the heavier side, averaging around 12-13 grams, we had to find oystercatchers heavy enough to carry them. Oystercatchers are relatively large shorebirds, but we were not prepared for how challenging it was to find heavy birds on the Delaware Bay! We captured around ten adults during the 2024 season, but only two birds met the mass criteria and were able to safely carry tracking units.

Step 3: Tracking the Birds!

Given our challenges with deployment this season, we were very happy to successfully tag and track two birds, an adult female named Snowflower and an adult male named Roy Royster. Each bird has their own unique story representing different aspects of “oystercatcher life” during the nesting season and beyond. Although we are still in the early stages of collecting and analyzing transmitter data, we are excited to share some snapshots of their movements and behavior so far.

Snowflower:

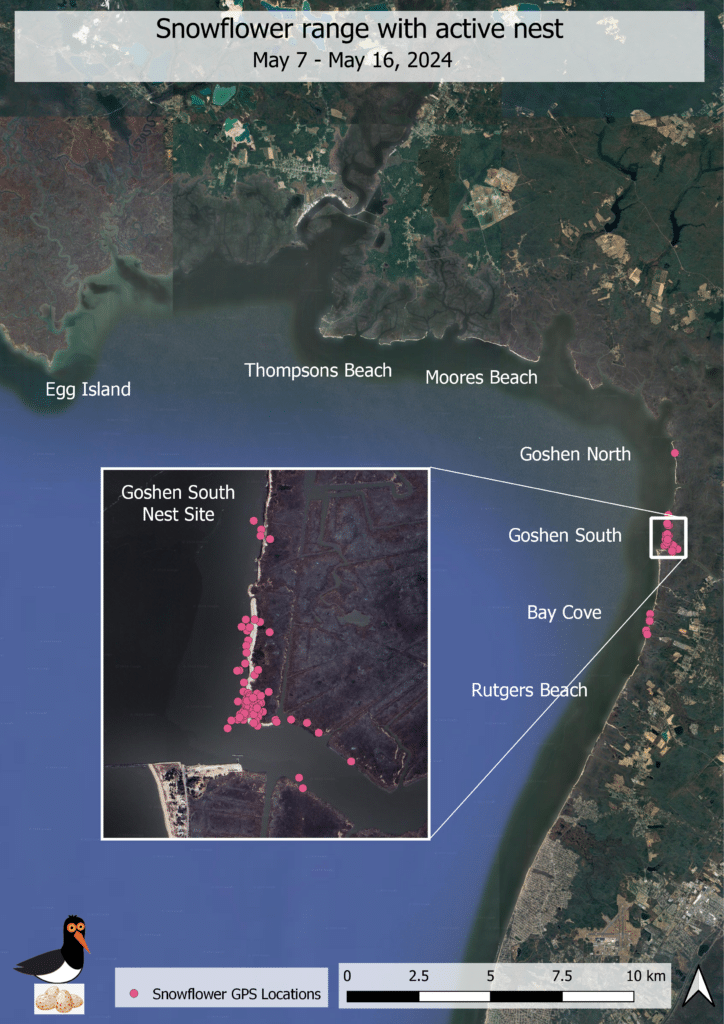

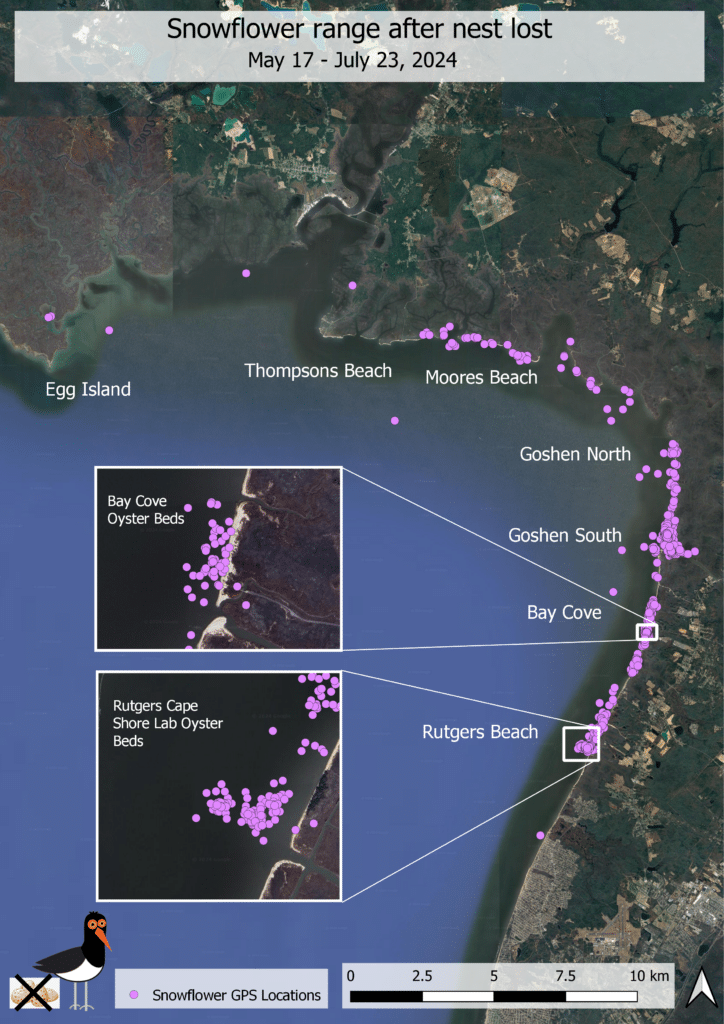

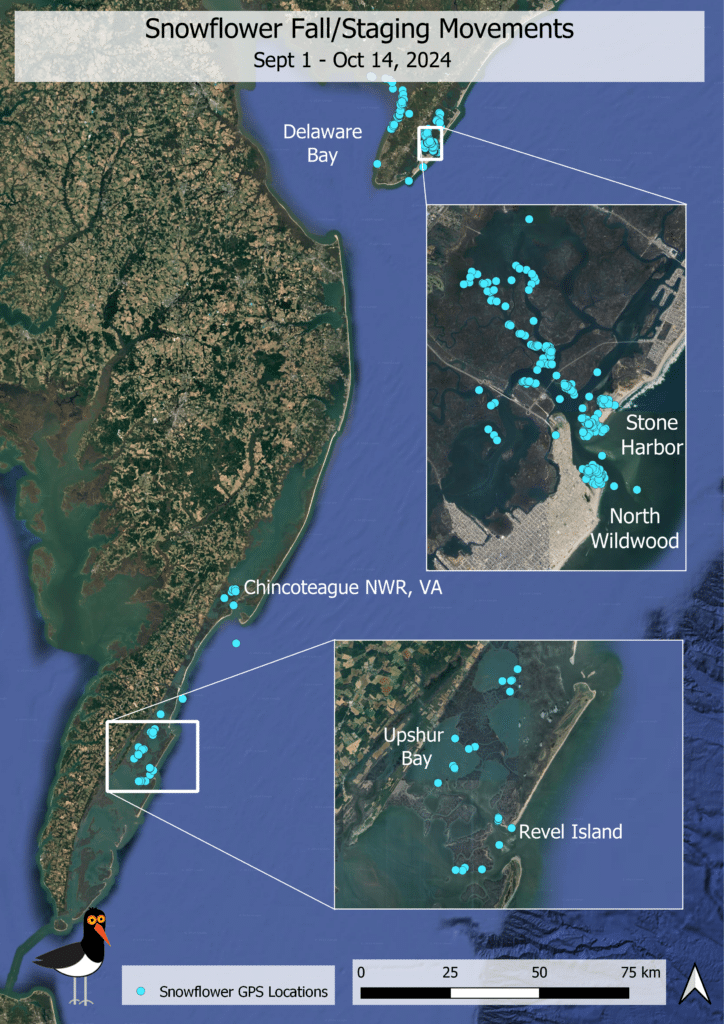

Snowflower was tagged on May 7, 2024 at South Goshen Beach, while tending an active nest with her mate King Nummy. Unfortunately, the pair lost their nest to fox predation nine days later on May 16th, but we were still able to collect some interesting movement data before and after the nest was lost. While incubating the active nest, Snowflower stayed close to her nest territory, with occasional foraging trips to the oyster beds/living shorelines at Bay Cove Beach (Map 1). Following her nest loss, Snowflower’s range expanded significantly to encompass much more of the Bayshore, spanning from Del Haven all the way up to Egg Island – a distance of 15 to 23 miles depending on possible flight routes (Map 2)! We were also interested to observe that she continued to make foraging trips to living shorelines/oyster beds at Bay Cove and Rutger’s Cape Shore Laboratory. Up until very recently, Snowflower has remained on the Cape May Peninsula, especially around Atlantic Coast sites such as Stone Harbor Point, a known oystercatcher staging and wintering roost location (Map 3). However, she recently surprised us by taking a brief “vacation” all the way down to the Eastern Shore of Virginia from October 10-12, only to return to New Jersey on the 13th (Map 3)! It remains to be seen whether she will stay in New Jersey year-round or head to a more southern winter location.

Roy Royster:

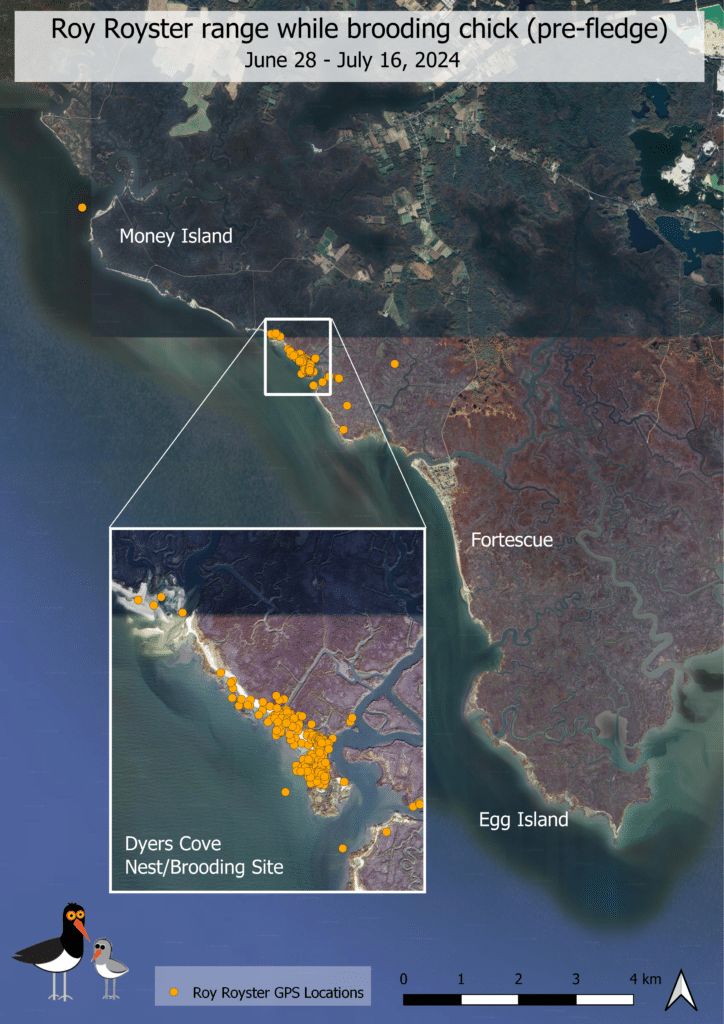

Compared to Snowflower’s transmitter deployment, Roy Royster’s story is filled with lots of ups and downs. After trying and failing to find oystercatchers heavy enough to carry transmitters, we were so ecstatic to finally deploy our second transmitter on Roy on June 28th near Dyers Cove in Cumberland County. This was especially exciting for the team because Roy had successfully hatched a nest and was in the process of brooding his chick (Rudy Royster) with mate Rhonda. Oystercatcher chicks depend on food provisions from their parents until they are at least 60 days old when their beaks become strong enough to pry open bivalves, their primary food source. Large feeding areas close to nesting locations have been linked to increased fledgling success (Nol 1989), presumably because adults foraging closer to their offspring can devote more time and energy to chick care and protection. Since only three nests managed to hatch during the 2024 season, we felt very lucky to be able to collect GPS data on a brooding pair to help test that hypothesis.

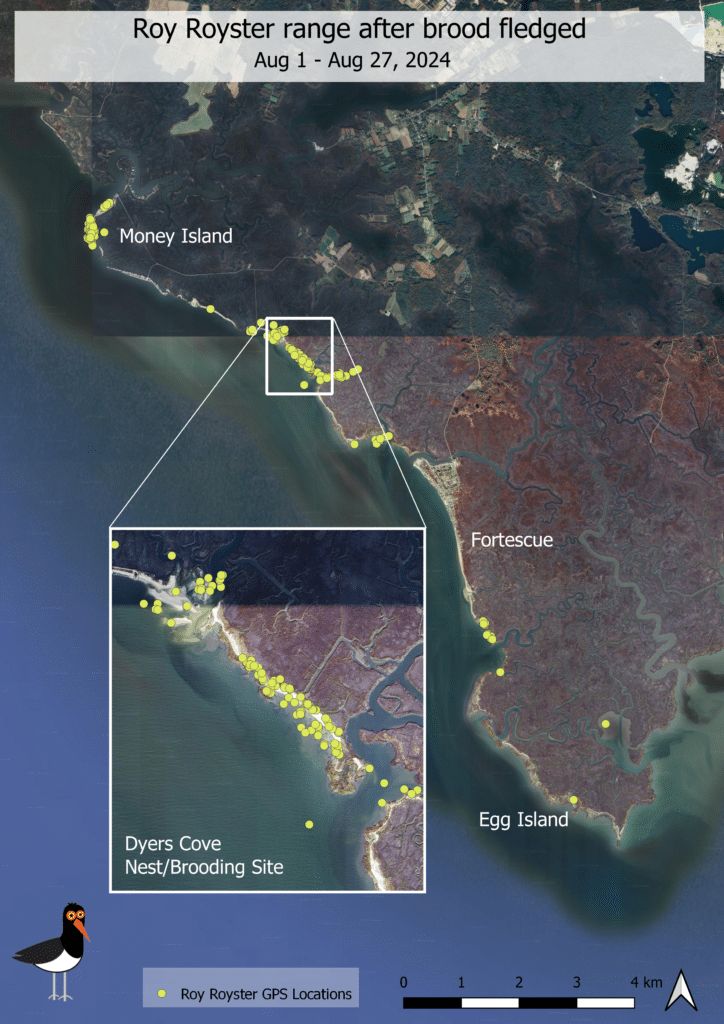

Unfortunately, Roy’s transmitter went silent almost immediately after deployment and didn’t transmit a single location after June 28th. We knew Roy was still alive and well based on field observations, but we couldn’t figure out why his transmitter wouldn’t work. After we had just about given up on receiving any data we were shocked when Roy’s transmitter finally checked in on September 11th, all the way from the Eastern Shore of Virginia! The transmitter also dumped hundreds of GPS locations stored before Roy left New Jersey, so we were able to map out some of his foraging patterns while brooding Rudy and after Rudy had fledged. While we don’t have fine-scale timing intervals, it seems like Roy stayed close to his brooding territory at South Dyers Cove (Map 4), potentially indicating the presence of abundant and high quality foraging resources. After Rudy fledged and was able to fly, Roy expanded his range, making trips to Money Island and Egg Island (Map 5). Roy’s migration data does have some gaps, so we can’t determine the exact route and timing of his migration south, but he continues to check in from Virginia (Map 6), coincidentally just a few miles from this year’s American Oystercatcher Working Group Meeting in Wachapreague. Sounds like the perfect opportunity for a field trip this December!

Next Steps

We look forward to continued tracking and monitoring of Roy Royster and Snowflower throughout the winter and the next nesting season, but Roy and Snowflower represent just the beginning of our telemetry efforts on the Delaware Bay. We are already troubleshooting challenges encountered during our first season, and we are excited to improve and expand oystercatcher tracking in the years to come. Make sure to stay tuned for future updates on this exciting addition to our Delaware Bay American Oystercatcher project.

We’d like to extend a huge thank you to the Cape May Point Science Center for providing the transmitters, Cellular Tracking Technologies for their assistance with harness design and transmission troubleshooting, and The Wetlands Institute for skillfully deploying the transmitters in the field. The Delaware Bay American Oystercatcher Project is made possible through a grant provided by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s Delaware Watershed Conservation Fund.