Science in the Mangroves

Update from Brazil: “We are Going to Have to Science the ‘Heck’ Out of This”

by Dr. Larry Niles, LJ Niles Associates LLC

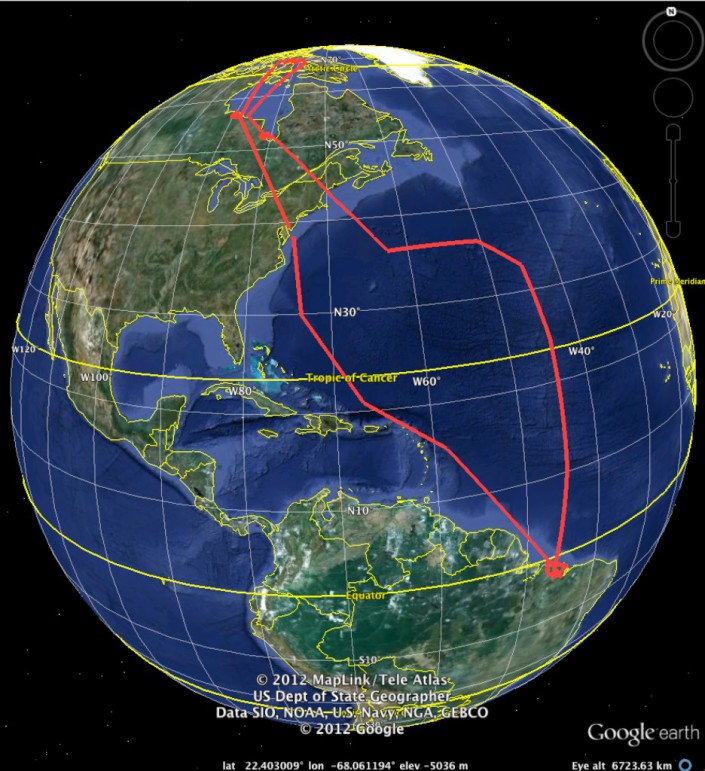

We came to Brazil to conduct a rigorous scientific study of the wintering population of shorebirds in a place where the land and sea act against any rigorous protocol. It would be easier to just go out and count birds and identify their habitats and prey, but our charge is more difficult.

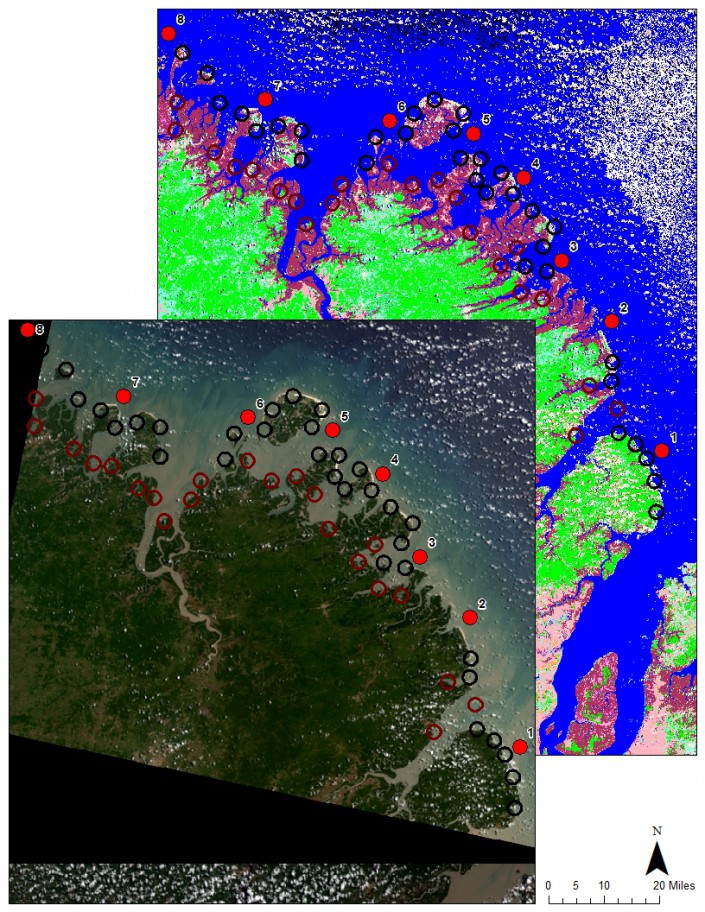

The survey wraps around satellite imagery, strange unintelligible wavelength data coming from satellites hovering over the earth that can be transformed into brilliant and useful maps in the right hands. Those hands belong to Professor Rick Lathrop and his post doc Dan Merchant. Rick leads the Center for Remote Sensing at Rutgers and he and I have collaborated on projects ranging from municipal habitat conservation planning to Arctic red knot habitat mapping. He has created one of the most alarming maps that every person from New Jersey should know about.

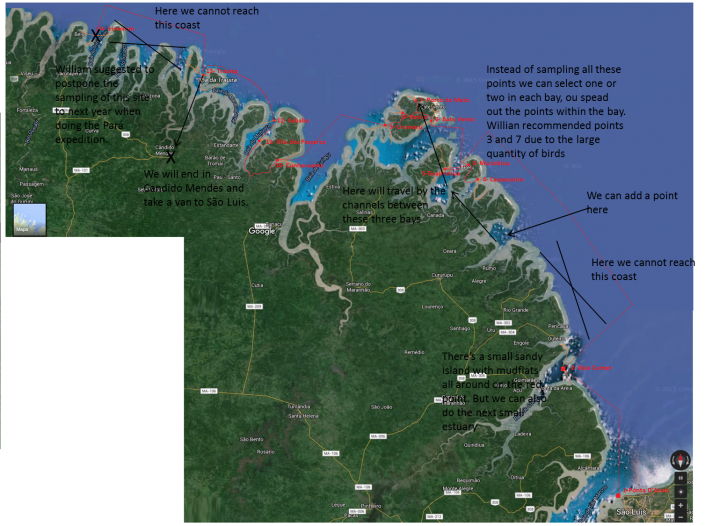

The mapping of Reentrancias Maranhenses, an internationally recognized site of ecological importance is especially tricky. Our research platform is a 50-foot boat and we will be out of cell and internet contact for much of the time. Our method of collecting data for the mapping was devised by the whole team, but especially with the help Professor David Santos of the University of Maranhao, my colleague Dr. Joe Smith and Humphrey Sitters of the International Wader Study Group.

It focuses on collecting bird and habitat information using randomly selected survey points. In other words, we will try to pick places at random to survey so that when we combine them we will have a sample that represents the entire area, not just the places we surveyed. It’s like trying to figure how many different kinds of chocolates are in a valentine. If you take them all from one side then you might have sampled the chocolate covered cherry section leading to believe they are all one kind. But if you choose chocolates at random than you will find the box includes other kinds, caramel or fruit or nutty chocolates. This is making me hungry, but you get the point.

The area of our box we is very large, bigger than New Jersey, and it grows and shrinks every day with the tides. So, sampling is tricky business because a sample at low tide, when the tide is out exposing vast areas of intertidal mud and sand flat, is very different than when the tide is high. So we will be classifying habitat, or stratifying it, so we can focus on limited survey time to get the best sample.

Once collected we can start making maps. All data will be geo referenced – or located precisely with GPS units – so it can be accurately mapped. With this, we will train the satellite maps to outline the habitat best for shorebirds.

All this while exploring areas that have received little scientific scrutiny and under tropical conditions, almost daily rain, a persistent 20 mph wind and summer heat. Add parasites, mosquitoes and diseases like malaria and one can see this a rugged undertaking.

Our crew is up to it. Besides those mentioned above Mark Peck from Royal Ontario Museum, Danielle Paluto from the Brazilian CEMAVE (a counterpart to our USFWS), Steve Gates a veteran of expedition on other SA trips, shorebird expert Dr. Mandy Dey, Stephanie Feigin from Conserve Wildlife Foundation of New Jersey and the author round out a dream team of bird study in difficult places.

Learn more:

- Conserve Wildlife Foundation’s Online Field Guide: Red Knots

- Conserve Wildlife Foundation’s Shorebird Project

Dr. Larry Niles has led efforts to protect red knots and horseshoe crabs for over 30 years.