By: David Wheeler, Conserve Wildlife Foundation of New Jersey Executive Director

With our eastern landscape largely devoid of top carnivores, bobcats are a throwback to the wild predators that once ruled our forests. No one understands that better than our partners from the New Jersey Endangered and Nongame Species Program (ENSP). The bobcat was listed as a state endangered species in June 1991, and habitat fragmentation in our densely populated state has made their recovery especially challenging. Biologists Mick Valent and Gretchen Fowles study bobcats in the wild, and here they generously share their insights on this remarkable creature.

What do you find most compelling about working with bobcats?

Mick Valent: I have worked with many species during my tenure with the Division of Fish and Wildlife including bald eagles, peregrine falcons, Allegheny woodrats and timber rattlesnakes, to name a few. However, to me, none epitomize the “wild” in wildlife the way that bobcats do. To me, they are the ultimate New Jersey predator – highly adaptive, perfectly camouflaged, keen senses of sight and sound, blazing speed and quickness, razor sharp claws and teeth, and the ability to stalk their prey quietly or overrun them! Fierce and unyielding, when captured, they are truly New Jersey’s little lion!

Can you describe the feeling of your first bobcat sighting?

MV: As chance would have it, I went many years without seeing a bobcat in the “wild” in New Jersey – even as the population was apparently increasing. Despite spending many days afield tracking and trapping bobcats, it wasn’t until 2011 that I saw my first bobcat (aside from the ones that I trapped and collared). I was in Allamuchy Township in January of 2011 searching for a suitable area to trap, when an adult bobcat bolted from a pile of tree stumps and logs right in front of me. A perfect spot for a bobcat to seek shelter during the daylight hours. And by the way, we were never able to catch that animal!

Are bobcats proving adaptable to New Jersey’s changing landscape and human development?

Gretchen Fowles: Bobcats seem to be increasing in northern New Jersey. In the past couple of years, there have been an increasing number of bobcat sightings south of Route 80 (though still north of Route 78), suggesting that they have been somewhat successful at passing through that tough Route 80 barrier. Our data suggest that bobcats are finding a way to move between core habitat areas in northern New Jersey. We have several males and females that have moved over 30 miles from year to year.

However, major roadways continue to be a problem. We have GPS collar data from a couple of bobcats that indicate that major roadways, such as Routes 80 and 206, seem to be perceived as complete barriers to these animals. The collars recorded movement patterns with location points going right up to and paralleling the road, but not crossing over it. We have been monitoring about 12 crossing structures under major roadways in northern New Jersey that bisect suitable bobcat habitat.

What are the worst threats to bobcats in New Jersey?

GF: Habitat fragmentation and roads are the worst threats, and they’re getting worse. A young bobcat was hit by a car and was found on the shoulder of westbound Route 78 last year. So, they are trying to cross that barrier, but are having difficulty doing so. Another bobcat was hit by a car in Parsippany when attempting to cross Route 46. The final quarter of each year, between October and January, tends to be the peak period for bobcat road mortality, and it is important that people report these incidents to the ENSP. We are working on a project called Connecting Habitat Across New Jersey (CHANJ) that is aimed at reconnecting the landscape for terrestrial wildlife, like bobcats.

We have formed a multi-partner, multi-disciplinary working group to inform the development of this statewide connectivity plan that will help target local, regional, and state planning efforts and ultimately reconnect the landscape in New Jersey. We are mapping the core habitat areas in the state as well as the corridors that can serve to connect those areas together, and are working on a Guidance Document that will recommend ways in which those cores and corridors can be made more permeable through targeted land protection, habitat management and restoration, and road mitigation efforts. We are also developing a bobcat recovery plan.

The constant threat from habitat loss and fragmentation, changes in land use, the existence of barriers to free movement between suitable habitats, and automobile collisions on our busy and abundant roadways will likely limit the growth of New Jersey’s bobcat population. It is likely that bobcats will remain only locally abundant in areas of suitable habitat, primarily in the areas north of Interstate Route 80. Whether or not a few animals are successful at crossing our major roadways, they will always pose an impediment to free movement between suitable habitats and will continue to be a source of mortality to the population.

What are some of the ways you study bobcats in New Jersey? Are you still using dogs in this work?

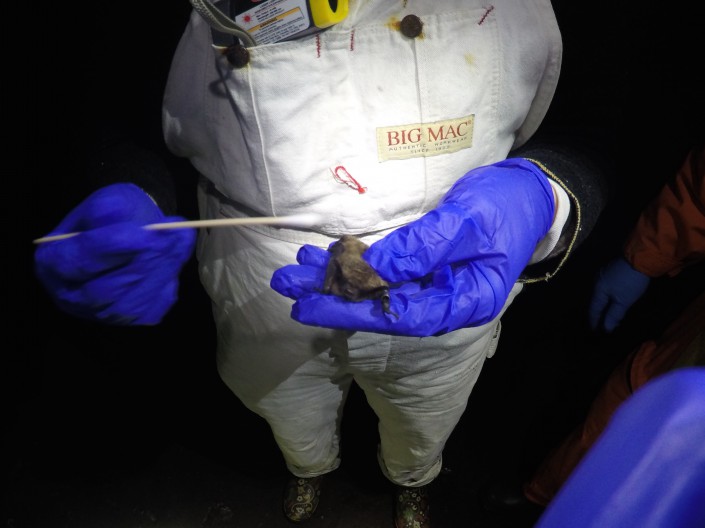

GF: We continue to use Bear, a professionally trained working dog for wildlife who is used to locate and alert biologists to bobcat scats, to help us better understand the New Jersey bobcat population. Bear is now about 12 years old, but his nose still works!

DNA can be extracted from sloughed intestinal cells contained in bobcat scat and can provide a wealth of information. DNA analyses of scat, as well as the locations where the scats are found, allow biologists to identify individual animals, their sex and movements. The DNA data from scats and tissue samples that we collect from bobcats killed on the road, accidentally snared, or trapped by ENSP in order to fit with GPS collars, are being fed into analyses that will help use estimate survival rate, population size and structure, and sex ratio.

We also collared three bobcats this past winter near major roadways, and set the collars to collect locations every hour. We are excited to retrieve the data from these collars in a few months to evaluate how those major roadways may be influencing the cats’ activity patterns and determine if, when and where they are crossing them. This information will help validate our CHANJ mapping and inform our Guidance Document.

Is the big picture for bobcat populations any different nationally?

GF: A recent national status assessment conducted by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service found that bobcats were generally increasing throughout their North American range. This appears to be holding true in New Jersey in areas where we have suitable habitat that is accessible to the population.

Tell me about your most memorable encounter.

MV: My volunteer and I had responded to a call from a trapper who accidentally caught a bobcat in his cable restraint during one of those January cold spells. The bobcat was caught on the bank of a medium-sized stream next to a footbridge. As we approached, the animal was pacing along the stream bank and jumping up on the foot bridge. As my volunteer distracted the animal, I came in from behind and jabbed the cat in the rump with a jab pole loaded with a tranquilizing drug. We immediately backed off to let the drug take effect so we could remove the cable from the animal’s neck. As the drug began to take effect the animal lost the ability to stand and slipped into the water – struggling to stay above the surface.

Without hesitation, we ran back to the stream. My volunteer arrived first, jumped into the frigid, chest-deep water, and grabbed the cat and pulled him to safety. Although the cat was not fully sedated, we were able to wrap him in a dry blanket, remove the snare from his neck and get him into the truck and off to a rehabilitation facility without incident. Everyone survived unscathed – although I’m certain the bobcat was much better prepared for going into the water than we were!

Learn more: